2.8.0

Polyvagal Social Engagement

In this chapter, we will explore what Polyvagal Theory has to say about communication and social engagement.

2.8.1

Polyvagal Social Hypotheses

The Polyvagal Theory makes the following predictions about social communication:

1. Phylogenetic: Mammals are social, and reptiles are asocial. From the PVT perspective, “reptiles” — a paraphyletic group — represent all non-mammals (fish, amphibians, and birds).

2. Value: Social contacts are good. They promote health, peace, and positive communication.

3. Facial interface: The social engagement system (VVC) supports social life. Facial expression is the primary social interface.

4. Physiological state: Sociality is associated with a state of safety and relaxation characterized by a parasympathetic tone. Sympathetic activation blocks social life.

To illustrate his narrative, Porges often presents images of touching mother-child exchanges. He focuses on humans and primates — only 6-8% of the 6000 species of mammals. Anthropocentrism. After a bit of searching, we found enough similar pictures of turtles, crocodiles, fish, and birds looking at each other. Thick scales, shells (turtles), or beaks don't facilitate close contact, but elephants don't kiss either.

2.8.2

Compared to What?

Porges postulates that evolution has set its agenda toward socialization. This teleological view leads him to many misconceptions about non-mammals.

Presenting mammals as the only social group among animals shows an obvious lack of knowledge about the animal world. Vertebrates and invertebrates (e.g., ants, bees, or termites) show sophisticated social networks. Life without sociality is simply unthinkable. A review of social versus solitary species reveals that they are evenly distributed between mammals and non-mammals.

Primates are the only group that practices face-to-face care. The remaining 93% of mammalian newborns suckle their mothers' breasts without facial contact. Similarly, 99% of mammals use “doggy style” or, more scientifically, “dorsal-ventral” or “rear-entry” intercourse. This also prevents face-to-face interaction.

Non-mammals Like to Play, Too (in Discovermagazine). Animal play isn't limited to mammals. From spiders to birds to octopuses, non-mammals also know how to have fun.

In our opinion, Porges misses the mark with this outdated, mammals-only perspective. Readers are encouraged to search YouTube or Sir Attenborough documentaries on wildlife and discover the diversity of life forms. Read also, Breaking the Social–Non-social Dichotomy: A Role for Reptiles in Vertebrate Social Behavior Research? (Doody, 2012) and The Evolution of Sociality and the Polyvagal Theory (Doody, 2023), both by top experts Doody, Burghardt, and Dinets.

2.8.3

Social Animals vs. Solitary Animals

Most social animals are also found in mammals and non-mammals (including invertebrates). The universal “social mammal” is a stereotype.

Non-mammals: termites, ants, bees, most birds, but especially penguins, many amphibians,

Mammals: killer whales, coyotes, hyenas, otters, wolves, chimpanzees, elephants, dolphins, lions, and dogs.

Most solitary animals. They prefer to eat, sleep, and hunt alone. They usually only come together when it's time to mate or raise their young.

Non-Mammals: Solitary Sandpiper, Desert Tortoise, Chuckwalla Lizard

Mammals: Platypus, Polar bear, Snow leopard, Moose, Hawaiian monk seal

YouTube: Bearded Dragon Comes Running When His Mom Calls Him

Most birds are highly social. Some bird species live in large colonies, have complex communication systems, and engage in cooperative behaviors such as hunting, foraging, and raising young.

Fish, amphibians, reptiles, and arthropods also have species that exhibit social behavior, but the complexity and scope of their social interactions tend to be less extensive than in birds. There are exceptions, however.

Certain insects, particularly eusocial species such as ants, bees, and termites, exhibit the arthropod group's most complex and organized social structures. Colonies of these insects can consist of millions of individuals working together in a highly coordinated manner, with distinct roles and responsibilities for different members of the colony.

Comparing all these groups, eusocial insects such as ants, bees, and termites are among the most socially complex non-mammalian species. Their social structures are incredibly sophisticated, and their ability to work together is unparalleled in the animal kingdom, except for a few mammalian species.

2.8.4

Sympathetic System and Bonding

While people often gather in pleasant, relaxed situations that promote a parasympathetic tone, there's no shortage of social opportunities with excitement (sports, dance, and musical events) and adrenaline. War and military life can be the starting point for extraordinary friendships and intense bonds.

We have also seen that noradrenaline (norepinephrine) promotes bonding.

2.8.5

Calling is Universal!

The PVT characterizes calling or vocalization as a uniquely mammalian phenomenon, which is incorrect. Even newly born fish or small crocodiles still in the egg call their parents.

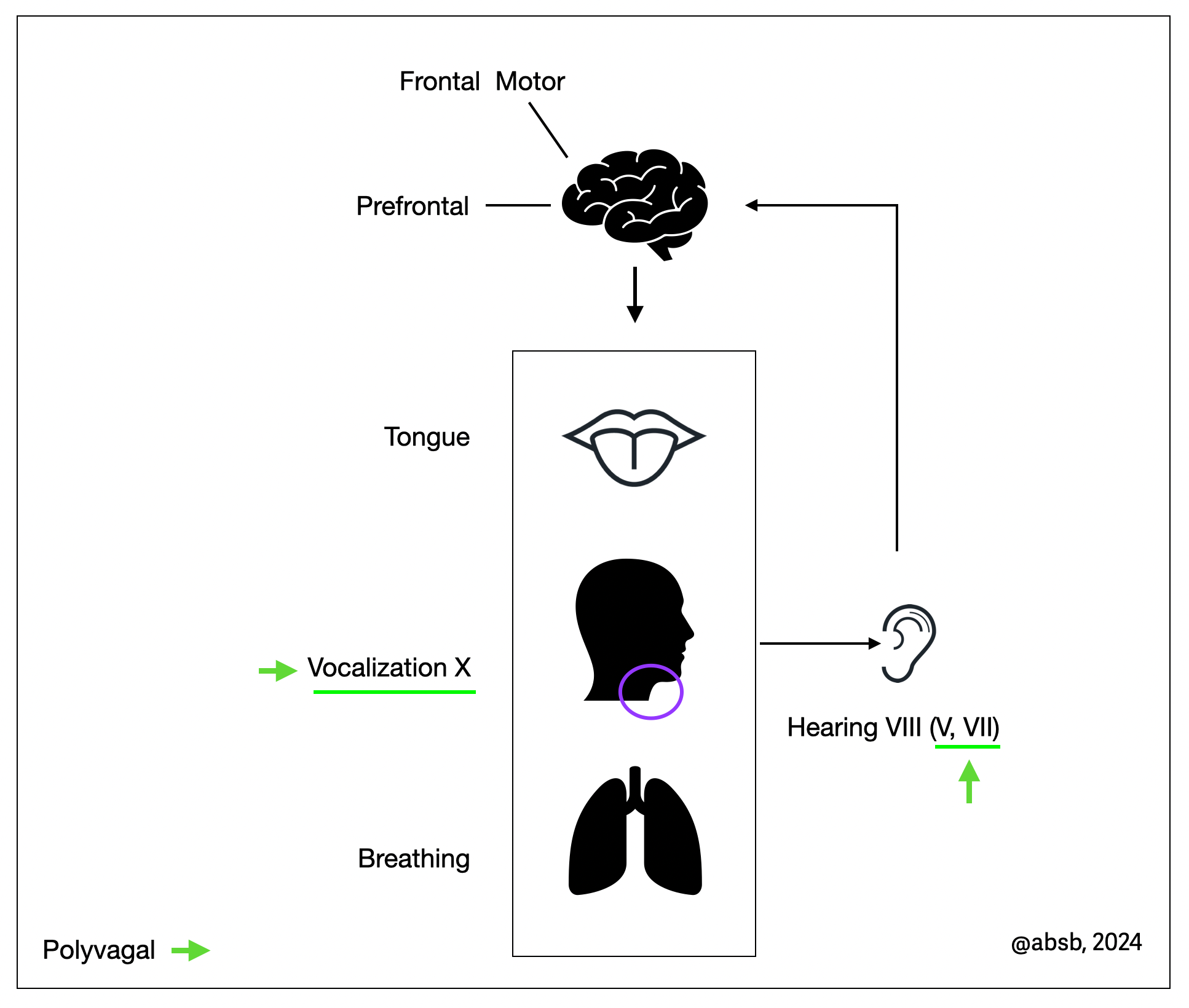

Moreover, human speech is produced not only by the VVC (branchiomotor X), but also by several organs: the respiratory muscles, the larynx (CN X), and the tongue (CN XII).

The PVT tends to think of mammalian vocalization as the only way. Several studies have shown how newborn fish communicate with adults through ultrasound. Male alligators meet at a large gathering and produce a rollicking vocal concert (Doody, 2021). So do frogs. As for birds, even children know how these graceful creatures express themselves each morning by marking their territory. In many groups, males produce species-specific vocalizations to attract females. Yamaguchi (2023) has even observed two anatomically distinct central pattern generators (CPGs) that drive the fast and slow clicks of a male frog, Xenopus laevis, during courtship.

Communication: the NTS is essential (Genetic identification of a hindbrain nucleus essential for innate vocalization (Hernandez-Miranda, 2017). Vocalization in young mice is an innate response to isolation or mechanical stimulation. Neural circuits controlling vocalization and respiration overlap and rely on motor neurons innervating laryngeal and expiratory muscles. The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) is essential for vocalization in mice. Newborn mice that specifically lack excitatory NTS neurons are both mute and unable to produce the expiratory drive required for vocalization. This results in maternal neglect. The NTS is directly connected to and controls the activity of the spinal motor pool (L1) and nucleus ambiguus, which contain expiratory and laryngeal motor neurons. The NTS is an obligate component of the neural circuitry that converts breaths into calls.

In Comparative vertebrate neuroanatomy : evolution and adaptation (Butler, Hodos, 2005, p. 211) the authors describe the communication systems of fish: sound and electrical communication, the sonic motor nucleus. Vocal muscles work like sticks beating on a drum (the swim bladder). The midbrain vocal-acoustic complex contains the PAG, which plays an essential role in tetrapod vocalization.

Automatic acoustic identification of individuals in multiple species: improving identification across recording conditions (Stowell, 2019). Many animals produce vocalizations that contain some individually distinctive signatures, regardless of the function of the sounds. Individual differences in acoustic signals have been widely reported in all classes of vertebrates..

Stowel, working at the Machine Listening Lab UK, describes the concept of Bioacoustics. He analyzes the mechanism of “denoising,” extracting signals by separating them from the background using algorithms. An example is the extraction of noise signals in a noisy environment.

Cooperative behavior evokes inter-brain synchrony in the prefrontal and temporoparietal cortex: A systematic review and meta-analysis of fNIRS hyperscanning studies (Czeszumski, 2021).

Neural Circuit Mechanisms of Social Behavior (Chen, 2018).

Correlated Neural Activity and Encoding of Behavior across Brains of Socially Interacting Animals (Kingsbury, 2019)

Variability in the mating calls of the Lusitanian toadfish Halobatrachus didactylus: cues for potential individual recognition (Amorim, 2008). Acoustic recognition systems have evolved where crowding, noisy backgrounds (such as in dense flocks of birds), or darkness reduce the role of olfactory and visual cues or increase the risk of confusion. Acoustic recognition is also advantageous when vocal animals defend long-term territories. In fish, acoustic recognition has been demonstrated in coral reef species that breed in dense colonies. Frogs and toads also form breeding choruses and establish long-term territories.

Autonomic control of cardiorespiratory interactions in fish, amphibians and reptiles (Taylor, 2010). Understanding communication systems is essential to the study of animal behavior and ecology, as the course of interactions between individuals is mediated by visual, olfactory, and vocal signals. In particular, vocal signals have been shown to play a critical role in determining the outcome of intra- and intersexual competition and in mediating agonistic or affiliative interactions between individuals.

Neuroanatomical Substrates of Rodent Social Behavior: The Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Its Projection Patterns (Ko, 2017).

Turtle Vocalizations as the First Evidence of Posthatching Parental Care in Chelonians (Ferrara, 2013).

Common evolutionary origin of acoustic communication in choanate vertebrates (Jorgewich-Cohen, 2022). Choanates are a group of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) at the transition from fishes to amphibians. This article reviews evidence for acoustic communication in 53 species from four major clades (turtles, tuataras, caecilians, and lungfish). Acoustic communication is fundamental to parental care, mate attraction, and other behaviors. Vocal recordings and a broad literature-based dataset show evidence for acoustic abilities in several groups previously thought to be non-vocal. Critically, phylogenetic analyses of 1800 species of choanate vertebrates reconstruct acoustic communication as a homologous trait. This suggests that it is at least as old as the last common ancestor of all choanates, which lived about 407 million years ago.

2.8.6

Parental Care Across Species: It’s Not Just for Mammals!

Nursing

Even the most mammalian trait, nursing, can be found in other species: 10 Animals That Make 'Milk' and Aren’t Mammals.

Not just mammals: Some spiders nurse their young with milk Spiders nurse. Although lactation and nursing are more commonly associated with mammals, other animals such as these jumping spiders do, the same (Goldman, 2018).

In The Evolution of Parental Care (Clutton-Brock, 1991), the author extensively compares the parenting behaviors of mammals and non-mammals. Similar to Richard Shine, he moves away from the narrow psychological anthropocentric perspective to focus on survival factors and energy costs.

How birds reacts to loss and how Do Birds Cope with Losing Members of Their Group?

Scientists capture rare footage of mother skink fighting a deadly brown snake to protect her babies Documentary .

Breastfeeding and Extended Maternal Dependence

In many mammalian species, prolonged lactation and prolonged dependence on the mother are associated with more significant opportunities for social learning and the development of social bonds. This extended period of maternal care allows for the transmission of social behaviors and the establishment of emotional solid bonds critical in shaping offspring's social and empathetic capacities.

Does breastfeeding promote social behavior?

While many mammals exhibit high levels of social behavior, there are enough examples in the animal kingdom, including some mammals, to challenge this view. Solitary mammals such as tigers, leopards, bears, or male African elephants are solitary animals. They interact with others primarily during mating or territorial disputes. In contrast, some non-mammalian species exhibit sophisticated social behaviors without the same level of maternal care as mammals. Some examples include social insects (ants, bees, and termites), cichlid fish, and birds (crows and ravens). This further complicates the idea that extensive maternal dependency is directly correlated with sociality. This shows that high levels of sociality and empathy are not exclusive to mammals with extended maternal care. Some mammals that receive significant early maternal investment do not necessarily become more social as adults, and conversely, many non-mammals exhibit sophisticated social behaviors without prolonged maternal dependence.

Scientists capture rare footage of mother skink fighting a deadly brown snake to protect her babies, an article about a mother lizard protecting her young from a snake.

In nature, there are several examples of animal species where the mother sacrifices herself for the survival of her offspring, a behavior known as matriphagy. Here are a few examples:

Maternal investment in a spider with suicidal maternal care, Stegodyphus lineatus (Solomon, 2014). The Stegodyphus lineatus, a spider species, is known for this behavior. After laying her eggs, the mother spider will care for them until they hatch. Once they do, she will regurgitate a fluid for them to feed on. Eventually, she will degenerate, and her spiderlings will consume her.

Deep-Sea Octopus (Graneledone boreopacifica) Conducts the Longest-Known Egg-Brooding Period of Any Animal (Robinson, 2014). It lays its eggs and guards them for months, apparently without leaving to feed. By the time the eggs hatch, the mother is emaciated and usually dies soon after.

The Pacific salmon is a well-known fish species. After spawning, adult salmon die, and their bodies provide nutrients for their offspring.

Parental investment through skin feeding in a caecilian amphibian (Kupfer, 2006). The mother grows an extra layer of skin, on which her offspring feed.

This self-sacrificing behavior observed in these species is not an indication of conscious martyrdom but an evolutionary adaptation that increases the chances of survival for the offspring.

2.8.7

The Role of Facial Expression in Communication

The facial expression is less important than the global body expression. Isn’t it common to wave a hand to your neighbor or co-worker without using facial expressions? Therefore, we can't take interfacial communication as the primary way to justify PVT. If this isn't true for humans, how can it be for non-primates? Body Cues, Not Facial Expressions, Discriminate Between Intense Positive and Negative Emotions (Aviezer, 2012) and What is missing in the study of emotion expression? (Straulino (2023) demonstrate that the facial expression is less indispensable than the global body expression.

Facing freeze: social threat induces bodily freeze in humans (Roelofs, 2010), investigates freezing as a defensive response, based on body sway and heart rate, in 50 female participants. Viewing angry faces induces significant reductions in body sway, bradycardia, and subjective anxiety.

Effects of Facial Muscles Exercise on Mental Health: A Systematic Review (Okamoto, 2021). The facial feedback hypothesis proposes that facial movements can influence emotional experience. Certain facial movements can be controlled voluntarily, while others occur primarily during “real” emotions. Different neural pathways mediate these two facial expressions. Voluntary smiles are initiated in the motor cortex and through the pyramidal motor system, whereas involuntary smiles are primarily initiated in the subcortical nuclei and the extrapyramidal motor system. Voluntarily producing and holding an expression can induce the corresponding emotion.

The Science of Facial Expression by Fernández Dols and Russell (2017) reunites a large panel of experts in facial expression in one handbook (540 pages).

Facial expressions elicit multiplexed perceptions of emotion categories and dimensions (Liu, 2022).

The many facets of facial interactions in mammals (Brecht, 2012)

Reading What the Mind Thinks From How the Eye Sees (Lee, 2017)

The role of facial response in the experience of emotion (Tourangeau, 1979)

The facial expression musculature in primates and its evolutionary significance

(Burrows, 2008).

Why Do Our Eyes Move When We Think? It's a very interesting YouTube documentary.

Facial expressions not only express and communicate emotions. They also play a critical role in human concentration and creativity. This is evident in intellectual pursuits, sports, and artistic endeavors. Many artists, especially in jazz, make intense facial expressions while immersed in their creative process. This is similar to manual expressions such as clenching fists to evoke a sense of strength and determination.

Recent studies have also revealed that facial expressions reinforce negative feelings. Postmarketing safety surveillance data reveals antidepressant effects of botulinum toxin across various indications and injection sites (Makunts, 2020) and Modulation of amygdala activity for emotional faces due to botulinum toxin type A injections that prevent frowning (Stark, 2023): the titles speak for themselves.

2.8.8

Beyond the Face: Communicating with Hands and Feet

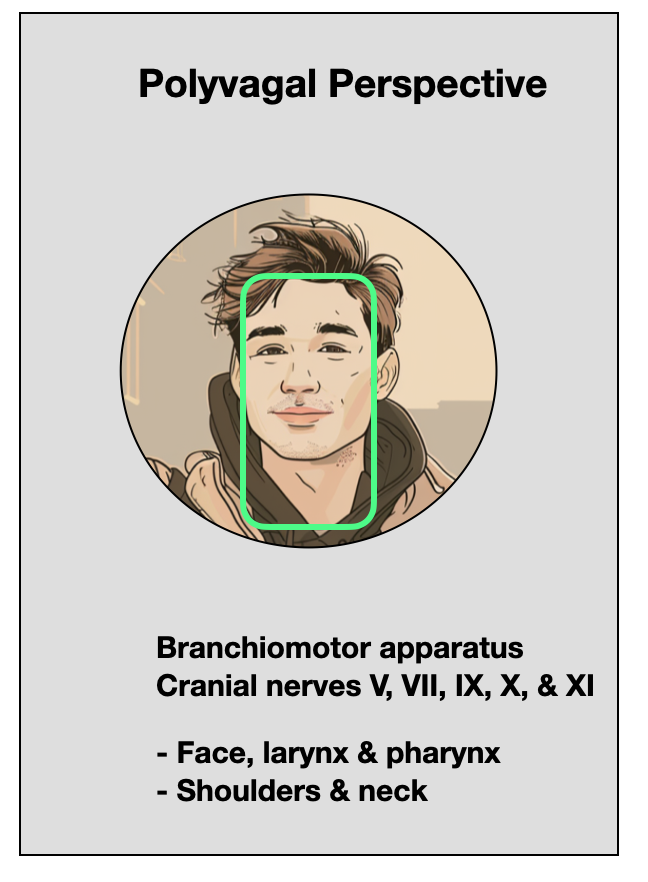

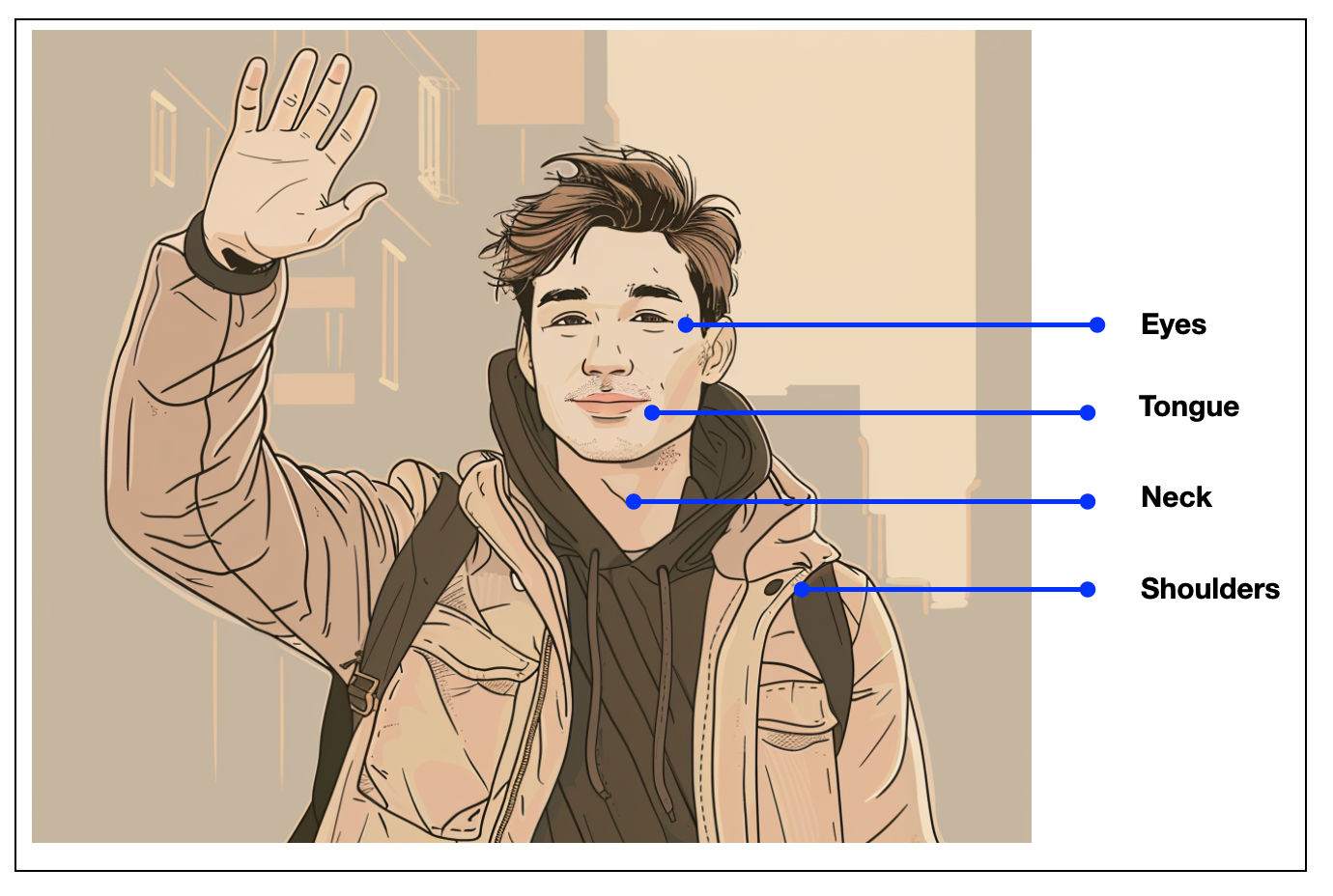

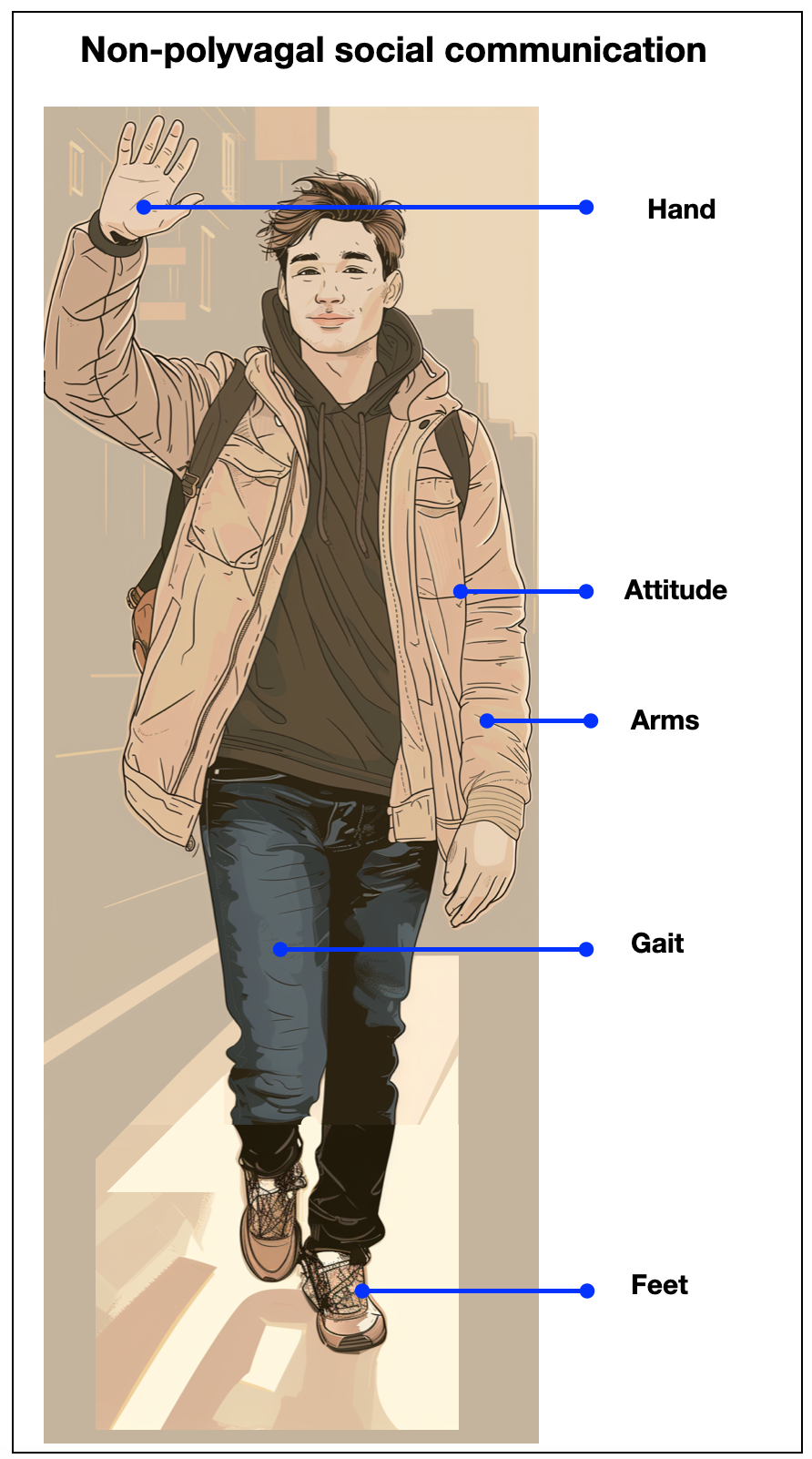

The PVT sees the motor cranial nerves (V, VII, IX, X, and XI) as the social hardware of social communication. Although the face, vocalization, and head rotation are important parts of communication, many other body parts are missing from this description.

Look at the face of a young man: the green square marks the part of the head that belongs to “social engagement”.

Now consider the next two images of the same young man waving with his right hand. Despite a neutral facial expression (closed mouth, half-open eyes), his gesture conveys a sense of friendliness. Hands, as powerful social signals, can be perceived from a great distance. Whether it's holding hands, caressing, or tapping, these actions are powerful social expressions. Arms can hold and embrace.

Eyes can look in multiple directions (cranial nerves III, IV, and VI). They are involved in emotions. The NLP technique has made a science of this. Looking “in the face” or looking away is full of meaning.

Speaking involves more than vocalization (larynx). Breathing (respiratory centers and muscles) and the tongue (cranial nerve XII) also modulate speech. The word “language” comes from the Latin “lingua,” the tongue.

The neck and shoulders use many muscles to turn, tilt, and move the head in all directions. The sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius (cranial nerve IX) are not the only ones in charge. At least five other muscle groups are involved: Splenius Capitis. Longus Capitis, Longus Colli, Suboccipitals and Scalenes.

The global posture of the body (upright, leaning forward, arms and legs closed or open) is a powerful expression.

The feet are also communicative. They remain invisible in video calls, so psychotherapists miss part of the body language. Feet don't lie! Finally, don't forget to play “footsie,” the hidden counterplay to holding hands.

Without the context of the raised right hand, we couldn't tell much about this woman's expression. Her posture (straight back) also adds meaning.

2.8.9

Eyes Movements and Polyvagal Theory

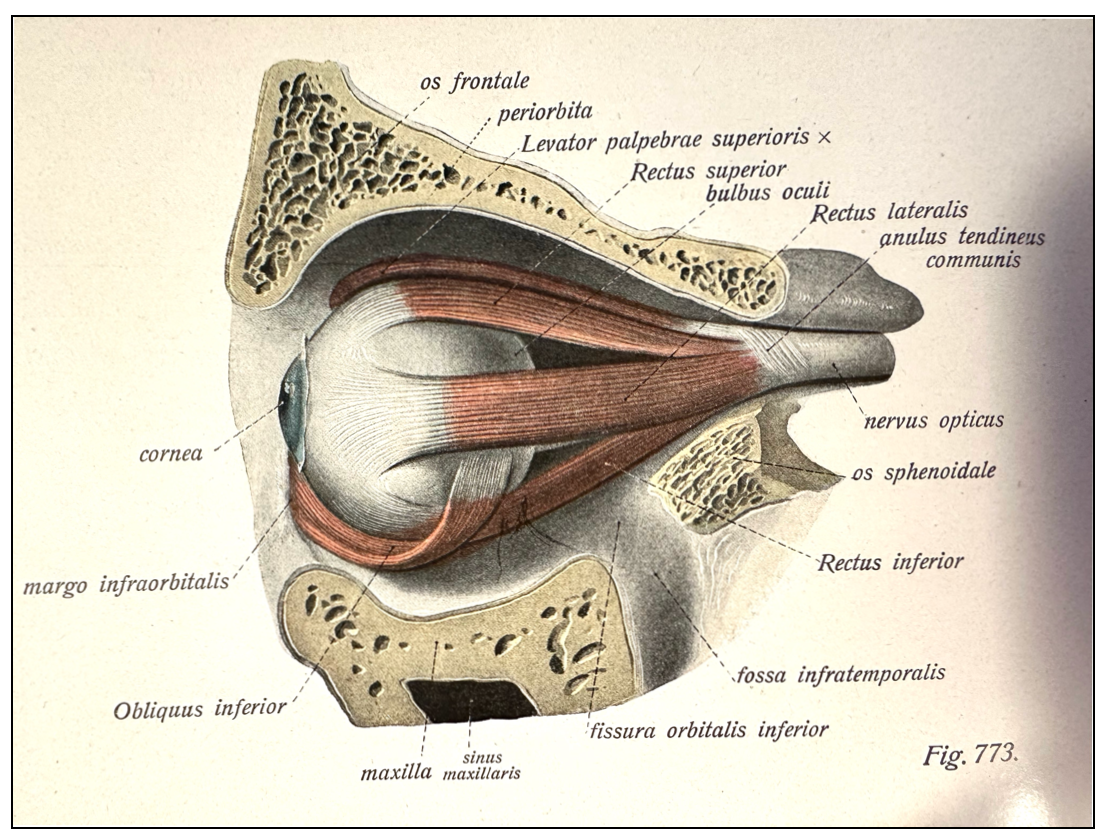

Extraocular Muscles

The eyes have many muscles to move them, to look up and down, right or left, or in any oblique direction (Figure from Sobotta, 1922). Cranial nerves III (5 muscles), IV (superior oblique), and VI (lateral rectus) are not branchiomotor nerves.

Humans can move their eyes in all directions. This increases their field of vision and enriches their facial expressions when communicating. People in shock often have a frozen expression. Moving the eyes (e.g., EMDR) can remove the psychological block. According to NLP, people look in different directions depending on their perception channel (e.g., visual, auditory, or kinesthetic). However, this knowledge is not widely accepted by scientists.

Intraocular Muscles

When the pupil dilates (sympathetic-driven Dilatator Pupillae), it signals interest and arousal. In the Middle Ages, women used Belladona (Italian for “beautiful woman”) tincture, which contains atropine, to dilate their eyes and increase their sex appeal. Cranial nerve III innervates the ciliary muscle (accommodation) and the pupillary sphincter — both parasympathetic.

2.8.10

Touch Me: the Oxytocin Factor!

Holding and hugging involve the whole body. In this type of communication, face-to-face exchange is reduced or even absent. According to The Oxytocin Factor (Uvnäs Moberg, 2003, p. 110), there is a strong link between oxytocin and touch. In mammals, the infant's oxytocin level isn't increased by breast milk, but by repeated and soothing stimulation.

Human C-Tactile Afferents Are Tuned to the Temperature of a Skin-Stroking Caress (Ackerley, 2014) shows that mechanoreceptors of non-myelinated fibers in the skin respond to slow repeated strokes, at human temperature.

TOUCH, The Science of the Sense that Makes Us Human (Linden, 2015) is a book about the skin, the anatomy of a caress, sexual touch, itching, and scratching!

2.8.11

The Evolution of Communication: A Phylogenetic Perspective

Multiple optic gland signaling pathways implicated in octopus maternal behaviors and death (Wang, 2018).

Co-regulation of hormone receptors, neuropeptides, and steroidogenic enzymes across the vertebrate social behavior network(Horton, 2018). The vertebrate basal forebrain and midbrain contain a series of interconnected nuclei that control social behavior. Conserved anatomical structures and functions of these nuclei have now been documented in fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, and these brain regions have become known as the vertebrate social behavior network (SBN). This study used RNA-seq to profile gene expression in seven brain regions representing five nodes of the vertebrate SBN in a passerine bird. Pipra filicauda. It provides functional insights into the neuroendocrine and genetic mechanisms underlying social behavior in vertebrates.

The Vertebrate Social Behavior Network: Evolutionary Themes and Variation (Goodson, 2005). Birds and teleosts (bony fish) possess a core “social behavior network” in the basal forebrain and midbrain that is homologous to the mammalian social behavior network. The nodes of this network are interconnected, contain receptors for sex steroid hormones, and are involved in multiple forms of social behavior. This study shows that the specific areas and peptidergic components of the social behavior network have functional properties that evolve in parallel with divergence and convergence in sociality.

Nonapeptides and the evolutionary patterning of sociality (Goodson, 2008) is an excellent article on the evolution of nonapeptides.

Committed for the long haul: Do nonapeptides regulate long-term pair maintenance in zebra finches? (Kelly, 2019). The nonapeptides (oxytocin, vasopressin, and their non-mammalian homologs) regulate many social behaviors in vertebrates, including monogamous pair bonding in mammals. Recent work in zebra finches (birds) has an essential role for these neurohormones in forming the avian pair bond.

Phylogenetic evidence for the modular evolution of metazoan signalling pathways (Babonis, 2017). Intercellular communication was paramount to the evolutionary increase in cell type diversity and, ultimately, the origin of large body size. Across metazoan diversity, we know of few conserved cell signaling pathways that orchestrate the complex cell and tissue interactions that regulate development; thus, modification of these few pathways has generated diversity during animal evolution.

The Evolution of Multicellularity: A Minor Major Transition? (Grosberg, 2007). The advantages of increased cell size and functional specialization have repeatedly driven the evolution of multicellular organisms from unicellular ancestors. Many requirements for multicellular organization (cell adhesion, cell-cell communication, coordination, or programmed cell death) likely evolved in ancestral unicellular microorganisms.

Social modulation of oogenesis and egg-laying in Drosophila melanogaster (Bailly, 2023). The authors show how female fruit flies modulate their reproductive output depending on their social context. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, females actively attract conspecifics to lay eggs on the same resources, forming groups where individuals can cooperate or compete. By laying eggs faster in a group than alone, females appear to reduce competition among offspring and increase offspring survival.

2.8.12

How do Opioids Affect our Social Behavior?

Under Sue Carter's influence, the PVT reduces the hormonal aspect of social life to oxytocin. It ignores the crucial importance of opioids (e.g., endorphins) in social life. PVT also gives endorphins a bad name, blaming them for the dissociative “dorsal” psychological shutdown. Ulrich Lanius, a polyvagal author, actually links post-traumatic dissociative phenomena to opioids and argues strongly for treatment with opioid antagonists (naloxone). In this section, we will look at the positive relationship between social connectedness and opioids.

Panksepp

In Born to Cry, chapter nine of The Archeology of Mind (2012), Panksepp introduces PANIC/GRIEF — one of seven basic affect systems. Young animals suffering from social isolation produce distress vocalizations (DVs). This specific behavior can also be induced with electrical simulations of the periaqueductal gray (PAG) or the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and some centers in the amygdala and hypothalamus (p. 323).

The last part of the chapter deals with the relationship between opioids and depression and explains why antidepressants can only partially alleviate the pain of grief. Panksepp tells us how he lost his daughter in 1991, killed by a drunk driver in a car accident when she was 16. He knows the terrible pain of loss.

Panksepp has long been interested in the connection between opioids and attachment.

The biology of social attachment: Opiates alleviate separation distress (Panksepp, 1978). Low doses of opiates can profoundly reduce crying, distress vocalizations, and motor agitation in socially isolated puppies. The reduction in crying achieved with morphine suggests the possibility that brain opiates may function to control the intensity of emotions resulting from social separation.

Endogenous opioids and social behavior (Panksepp, 1980) Opiates and opioids effectively reduce social separation-induced distress vocalizations (DVs) in puppies, young guinea pigs, and chicks, whereas opiate antagonists can increase DVs. In studies of specific social behaviors in rodents, morphine (at doses of 1 mg/kg and below) decreases proximity maintenance time, increases play, and decreases maternal aggression in socially housed animals but has no effect on pup retrieval. The data from this study are consistent with the proposition that brain opioids modulate social emotions and behaviors.

Many authors describe a correlation between the sense of touch and the production of oxytocin. However, opioid secretion also appears to be particularly sensitive to the soothing effects of touch (via slow conduction tactile C-fibers). Animals stop crying when gently touched. This effect is attenuated by opiate receptor blockade with naltrexone (or naloxone) and enhanced by low doses of opioids.

Oxytocin reduces habituation to opioids and prolongs their effects. Panksepp questions the source of the affective comfort — trust and security — classically attributed to oxytocin: could it, in fact, be primarily opioid-mediated?

Indeed, the literature shows that the loss of a loved one, through separation or death, produces the same response as opioid withdrawal or physical pain.

Effects of morphine and naloxone on separation distress and approach attachment: evidence for opiate mediation of social affect (Herman, 1978). In infant guinea pigs, crying or separation-induced distress vocalizations are significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner by single injections of low doses of morphine (0.25, 0.050, and 0.75 mg/kg). The antagonist naloxone increases separation distress vocalizations in juvenile and adult guinea pigs. This study supports the hypothesis that an endorphin-based, addiction-like process may underlie the maintenance of social bonds and that separation distress may reflect a state of endogenous endorphin withdrawal.

Opioids and social bonding: naltrexone reduces feelings of social connection (Inagaki, 2016). See below.

Naltrexone alters responses to social and physical warmth: implications for social bonding (Inagaki, 2019). 80 participants were randomly assigned to receive the opioid antagonist naltrexone or placebo. Neural and emotional responses to social and physical warmth were recorded. Social and physical warmth led to similar increases in ventral striatum (VS) and middle insula (MI) activity. However, naltrexone (vs. placebo) disrupted these effects by reducing VS and MI reactivity to social and physical warmth, erasing the subjective experience-brain association to social warmth, and disrupting the neural overlap between social and physical warmth. Social and physical warmth appear to share neurobiological, opioid receptor-dependent mechanisms.

Shifting the sociometer: opioid receptor blockade lowers self-esteem (Tchalova, 2023). 50 mg of naltrexone (an opioid receptor antagonist) and placebo were administered to 26 male and female participants. Participants reported lower levels of self-esteem — especially self-liking — on the naltrexone (vs. placebo) day. The tendency to accept (smile) faces — a perceptual process designed to maximize opportunities to reestablish social connection — was more significant on the naltrexone (vs. placebo) day, indicating increased social need under opioid receptor blockade.

Psychological Withdrawal: What You Need to Know Drug withdrawal vs. psychological withdrawal.

Intense, Passionate, Romantic Love: A Natural Addiction? How the Fields That Investigate Romance and Substance Abuse Can Inform Each Other (Fisher, 2016).

Heartbreak Looks a Lot Like Drug Withdrawal in the Brain (Bear, Drake, 2017).

Molecular neuropharmacology : a foundation for clinical neuroscience (Nestler, 2020). This article reinforces the view that physical and emotional suffering share the same support. The authors argue against the separation of physical withdrawal symptoms from psychological withdrawal symptoms. This separation is artificial and ignores the current understanding of behavior. All behavior results from physical, cognitive, and emotional forces, all of which are interrelated. There is no such thing as a purely “psychological” or “emotional” type of behavior unrelated to some physiological process. Likewise, any significant “physical” or “physiological” process will likely have associated emotional and cognitive ramifications.

Social Brain

The brain opioid theory of social attachment: a review of the evidence (Machin, Dunbar, 2011). Robin Dunbar is a British biological anthropologist famous for setting the maximum “cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom a person can maintain stable relationships” (150). Considering the number of publications on the “social brain,” most of which involve cortical functions, we may wonder how PVT can reduce social phenomenology to a tiny zone of the brain stem.

In The social brain hypothesis and its implications for social evolution (2009), Dunbar argues that the main reason the human brain grew (doubling in volume between Homo habilis and Homo sapiens) was social. Going beyond the “Dunbar number,” humans suddenly had a very complex social life where manipulation (Machiavellian brain) and calculation became crucial.

2.8.13

Is There a Reptile in All of Us?

Metaphorically, and consistent with the model, antisocial and pathological behavioral patterns associated with rage and hyperreactivity without conscious self-regulation have been labeled« reptilian.»

Orienting in a Mammal World (Porges, 1994)

In The Archaeology of Mind, Panksepp (2012, p. 288), writing about the evolution of the caregiving system, asks, “How could the powerful mammalian urge to nurture have evolved from ancestral beginnings in the brains of reptiles, animals that are notoriously non-caring parents?”

Reptiles, especially snakes, are the most neglected animals in the world. For a good dramatic story, reptiles are always welcome guests. They will always play the role of the villain. In our eternal desire — or obligation — as humans to become better people, after the snake of Eden got us kicked out of paradise, isn't it expected that we would be deeply suspicious of reptiles? Approximately 8,000 people in the United States are bitten by snakes each year. Reptiles are often seen as cold, ruthless, antisocial, and dangerous animals-a kind of disgrace to this creation. But science is here to separate fiction from nonfiction.

Audre Lorde, a black lesbian feminist, poet, and activist, made significant contributions to our understanding of “othering,” a process by which dominant groups, such as whites, portray marginalized groups, such as blacks, as fundamentally different or inferior. This denies the human equality of another group. It asserts unfounded differences. While demographic factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity are important in contexts such as health surveys, it's critical to distinguish between acknowledging diversity and perpetuating harmful stereotypes through othering.

Reptiles and literature

Before we get to the facts, let's see how MacLean's vision inspired Dragons of Eden (Sagan, 1977) or The Ghost in the Machine (Koestler, 1967). Both authors were interested in science. A gifted physicist who always had one foot in parallel worlds (Seligman, 2018), Carl Sagan was “a virtuoso of Soul-2 in science” (Dawkins, 2017, p.213). Koestler and Sagan invented a genre of literature in which speculative scientific theories flirt with the imagination — just what the masses love! Consider the enormous success of The Da Vinci Code: suddenly, readers felt entitled to know all about Jesus' parentage and all the hidden secrets.

Asocial reptiles?

The first thing you will see when you search for modern information about reptiles is how wrong our assumptions are. Compared to other animal groups (mammals, bees, birds, and fish), many reptiles don't exhibit an exuberant social life. However, looking for the most isolated animals, we find a complete mix of mammals and non-mammals: Platypus, Polar Bear, Snow Leopard, Solitary Sandpiper (bird), Moose, Desert Tortoise, Hawaiian Monk Seal, and Chuckwalla Lizard. Even wild cats can be solitary.

On the other hand, Capybaras, Dogs, House Cats, Dolphins, Bearded Dragons, Rabbits, Horses, Sheep, Swans, and Llama are among the friendliest animals. Termites, Bees, Chimps, Meerkats, Lions, Elephants, Penguins, Otters, Flamingos, Coral Reef Fish, and Wolves are the most social animals.

But on this list, we should see many more fish, amphibians, and birds which display extraordinary social behaviors. The separation of mammals/non-mammals, based on the myelinization of the ventral vagal nerve, is an erroneous consideration, as some snakes possess a myelinated efferent vagal nerve. Similarly, viewing the metabolic shutdown (as seen in the dive reflex) or the immobilization behavior as typically non-mammalian is wrong. Those behaviors are represented in all classes of vertebrates. Assuming that the fight-flight phenomenon is a mammal hallmark is wrong. The cliché of passive reptiles occludes that many non-mammals may display aggressive predating behaviors (e.g., sharks, crocodiles, snakes, or birds).

Doody, Dinets, and Burghardt - two biologists and a psychologist — are the leading researchers in reptile ecology. In Breaking the Social-Non-social Dichotomy: A Role for Reptiles in Vertebrate Social Behavior Research? (Doody, 2012), they wrote the first article to challenge the stereotype of asocial reptiles. Together, they published The secret social lives of reptiles (Doody, 2021), an exciting book on the social lives of reptiles. Covering species ranging from garter snakes to Komodo dragons, the authors delve into the evolutionary origins of social behavior in vertebrates and describe the diversity of social systems recorded in reptile taxa. In 2023, the same authors published a critical article on the Polyvagal Theory: The Evolution of Sociality and the Polyvagal Theory (Doody, 2023).

They were not the first, as in 1969 Gans published Biology of the reptilia (Gans, 1969), a book devoted entirely to the hidden life of reptiles. This book explicitly criticizes the restrictive perspective of many ecologists who didn't try to look more closely at the social behavior of reptiles. The book includes a chapter on Parental care in reptiles by Richard Shine and The physiological ecology of reptilian eggs by Gary and Mary Packard.

Of Iguanas and Dinosaurs: Social Behavior and Communication in Neonate Reptiles (Burghardt, 1977)

Pheromone communication in amphibians and reptiles (Houck, 2009)

Social behavior and pheromonal communication in reptiles (Mason, 2010)

Arginine Vasotocin, the Social Neuropeptide of Amphibians and Reptiles (Wilczynski, 2017)

The reptilian mistake

The mistake of MacLean, Koestler, and finally, Porges is to assume that humans have something reptilian in us. The two evolutionary paths diverged about 320 billion years ago (Roth, 2013). One leads to the stem mammals and the other to the “reptiles” (an artificial group), the dinosaurs, and the birds. This irreversible split was first expressed in a tiny difference in the skull (synapsids vs. sauropsids). It probably took another 150 million years before modern mammals appeared. However, contrary to the story of small mammals hiding from terrifying dinosaurs, paleontologists have shown that stem mammals were often large and robust, able to take on the reptilian monsters. After the great extinction of 66 mya, which left only small animals alive, all vertebrates began a new cycle of evolution without dinosaurs.

It's a romantic vision to think that our brains are made up of relics from the past. The genetic blueprint of mammals shares many features with the rest of the animal kingdom (invertebrates and even unicellular species). Thus, studying the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) allows us to understand our day-night rhythms. The zebrafish is an excellent model for observing helpless behavior. The tripartite brain (forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain) was established 600 mya. Therefore, the idea of an independent primitive reptilian or tripartite brain is nonsense in the light of modern biology.

Reptiles as an epic tale

Why does Porges keep comparing mammals to reptiles and not to fish, amphibians, or birds? He paints a picture of a dystopian, asocial creature immobilized by any threat. This is not based on scientific observation. The dichotomy of isolated reptiles versus social mammals is naive. Could something other than science be unconsciously at play — a good story? Speculative, astonishing revelations are the winning factor for the press industry. With the Polyvagal Theory, we have a “scientific” story of sin and redemption — from reptile to polyvagal-informed human.

The reptilian element in narratives resonates with audiences through cultural associations, primal fears, psychological concepts, and symbolism. The “reptilian” element has often been a compelling narrative theme in various contexts, such as mythology, literature, and psychology. Reptilian creatures are powerful archetypes for evil or antagonistic figures, tapping into deep-seated human emotions and fears.

There are several reasons for this negative fascination with reptiles:

Many cultures have historically associated reptiles with symbolic meanings. For example, in Christianity, the serpent in the Garden of Eden represents temptation and evil, while in ancient Egyptian mythology, snakes such as Apep were associated with chaos and destruction. These cultural associations contribute to the appeal of reptilian elements in storytelling.

Primal fears: Reptiles, especially snakes and giant lizards, can evoke primal fears in people because of their potentially dangerous or venomous nature. This instinctive reaction may be linked to our evolutionary history, where early humans had to be cautious around such creatures to ensure survival.

The “otherness” of reptiles: Reptiles are quite different from humans in appearance and behavior, making them seem more alien and mysterious. This sense of otherness can create a sense of unease or fascination, making reptilian creatures more compelling as narrative subjects.

Archetypal Evil Figures: The reptilian element often serves as a powerful archetype for evil or antagonistic characters, tapping deep-seated fears and cultural symbolism. For example, the serpent Nagini is associated with Voldemort's dark, sinister character in the Harry Potter series.

In the Triune Brain Theory, the “reptilian brain” refers to the most primitive part of the human brain, responsible for basic survival instincts such as territoriality. This concept reinforces the idea that reptilian elements represent primal, instinctual aspects of human nature.

Are humans better than reptiles?

In the last 150 years, human violence against conspecifics (= other humans) has caused millions of deaths:

Genocides and man-made famines: 36-85 million deaths

Wars: 110-150 million deaths

Victims of isolated murder among the civilian population (criminal causes) are omitted here.

The reptilian dystopia is a myth

Reptilians may not always be friendly when we bother or attack them. Like certain mammals, they may kill or even eat their conspecifics or broods. However, they will never wage organized wars like humans and, like Napoleon, send 600,000 young men to their deaths in a selfish war against Russia. That would require a highly developed cortex.

The development of such violence is specific to Homo sapiens. Such wars and exterminations are not known from any other species worldwide. Animals don't create wars or genocides out of males fighting each other (mostly without killing) for territory or females. There are, however, problematic cases of parasitism. In addition, no species has ever developed weapons of destruction (nuclear weapons) capable of quickly wiping out life on Earth, assuming that all world leaders would simultaneously press the nuclear button. This is impressive and sad. Greed, paranoia, lack of empathy, religion, and ideologies are usually the causes. In this case, blaming the “evil snake” or the “reptilian brain” is unfair. Ideologies are forged in the cortex, not the brain stem. Greed — wanting more — requires abstraction. Armies require organization. Even the barbaric Shoah required careful logistics.

Chameleons communicate with complex color changes during competitions: different body regions convey other information (Ligon, 2013).

According to Evolution of Cortical Neurogenesis in Amniotes Controlled by Robo Signaling Levels (Cárdenas, 2018), the difference between mammalian and reptilian cortex (not “reptilian brain”) is due to a slight genetic divergence. Two pathways promote either rapid direct neurogenesis (reptiles and birds) or indirect, slower neurogenesis.

Low Robo and high Dll1 signaling are required for indirect neurogenesis

Blocking Robo and high Dll1 in non-mammals induces indirect neurogenesis and SVZ

High Robo-low Dll1 blocks indirect neurogenesis in human brain organization.

2.8.14

Is Heart Rate Variability a Social Marker?

Porges presents HRV (heart rate variability) as a positive sociability index. Beauchaine et al. (2007) subsequently investigated and questioned a possible correlation between antisocial behavior and reduced HRV. Citing an earlier publication, the authors begin with« Polyvagal Theory has emerged as an important explanatory construct for a wide range of psychiatric conditions (Beauchaine, 2001). » Later« The DMX branch, sometimes referred to as the vegetative vagus, is rooted in the primary survival strategy of primitive vertebrates, amphibians, and reptiles, which freeze when threatened. ». The false narrative of dorsal freezing is endorsed without questioning.

In Heart rate variability as a transdiagnostic biomarker of psychopathology (Beauchaine, Thayer, 2015), Beauchaine states that “HF-HRV is related to activity in the PFC (prefrontal cortex), in part via cortical–subcortical connectivity, and that this relationship is disrupted in patients with major depression.”

A year later, he acknowledged that, although prominent neurobiological models of trait vulnerability to psychopathology existed (e.g., Fowles, 1988; Gray, 1982; Porges, 1995), they were difficult to confirm or falsify (Beauchaine, 2016).

Four years later, in Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity across empirically based structural dimensions of psychopathology: A meta-analysis, Beauchaine et al. (2019) were much more cautious in their claims: «These findings indicate that associations between RSA reactivity and psychopathology are complex and suggest that future studies should include more standardized RSA assessments to increase external validity and decrease measurement error.»

Cattaneo et al. in Is Low Heart Rate Variability Associated with Emotional Dysregulation, Psychopathological Dimensions, and Prefrontal Dysfunctions? An Integrative View (2021) states that« HRV is a variable that in influencing different dimensions such as Frontal Lobe Functions and Emotion Dysregulation contributes to the development of psychopathology (…) and above all, it is a bidirectional system between central elements and peripheral/autonomic elements.»

The PVT repeatedly uses this “bidirectional” argument to prove the bottom-up role of the ventral vagal complex. However, even though it is expressed in milliseconds, HRV is only an index of the variability of a complex system. An index is not a direct value, like “How much gasoline do I have in the tank? It's not an amount of acetylcholine or epinephrine. Nowhere in the brain is HRV registered and interpreted.

Porges uses the vagus's bidirectionality (motor + sensory), as described by Darwin, to promote the idea that the VVC and the HRV modify our state (how do we feel?). From this perspective, HRV is reified and becomes a quantity, like a neurotransmitter or a hormone.

Later, Cattaneo writes:« Subjects with high rest HRV can dispose of a better skill in adaptation to environmental stressors and better cognitive responses to emotional stimuli (…) Conversely, people with low HRV show worse activation in the prefrontal cortex, the rostral cingulate cortex, and the parietal cortex, and worse ability to dominate mental and behavioral impulses (…) In fact, as conceptualized by the Polyvagal Theory, physiological states may influence a wide range of social behaviors emitted, such as the ability to regulate emotional expressions and neural regulation of the social engagement system. This framework explains how HRV may be a marker of specific central pathways activation coming from cortical and subcortical areas (involving the temporal cortex, the central nucleus of the amygdala, and the periaqueductal gray) involving the regulation of both the vagal component and the somatomotor component of the social engagement system. »

To us, this is a circular argument.

In Resting autonomic nervous system activity is unrelated to antisocial behavior dimensions in adolescents: Cross-sectional findings from a European multi-center study, Prätzlich et al. (2019) conclude: «The Polyvagal Theory has been used to explain the link between the ANS and antisocial behavior (Beauchaine et al., 2007). Despite its highly regarded, explanatory role for research findings of psychopathology and emotion dysregulation (Beauchaine et al., 2007), its biological validity has been questioned, and the basic assumptions of the theory appear to have been falsified (Farmer, Dutschmann, Paton, Pickering, & McAllen, 2016; Gourine, Machhada, Trapp, & Spyer, 2016; Grossman, 2016; Grossman & Taylor, 2007).»

In conclusion, HRV may be a marker - not the cause - of mental and organic disorders (e.g., depression, cancer, or cardiovascular pathologies), but not of asocial tendencies.

2.8.15

Is Safety the Only Purpose of Life?

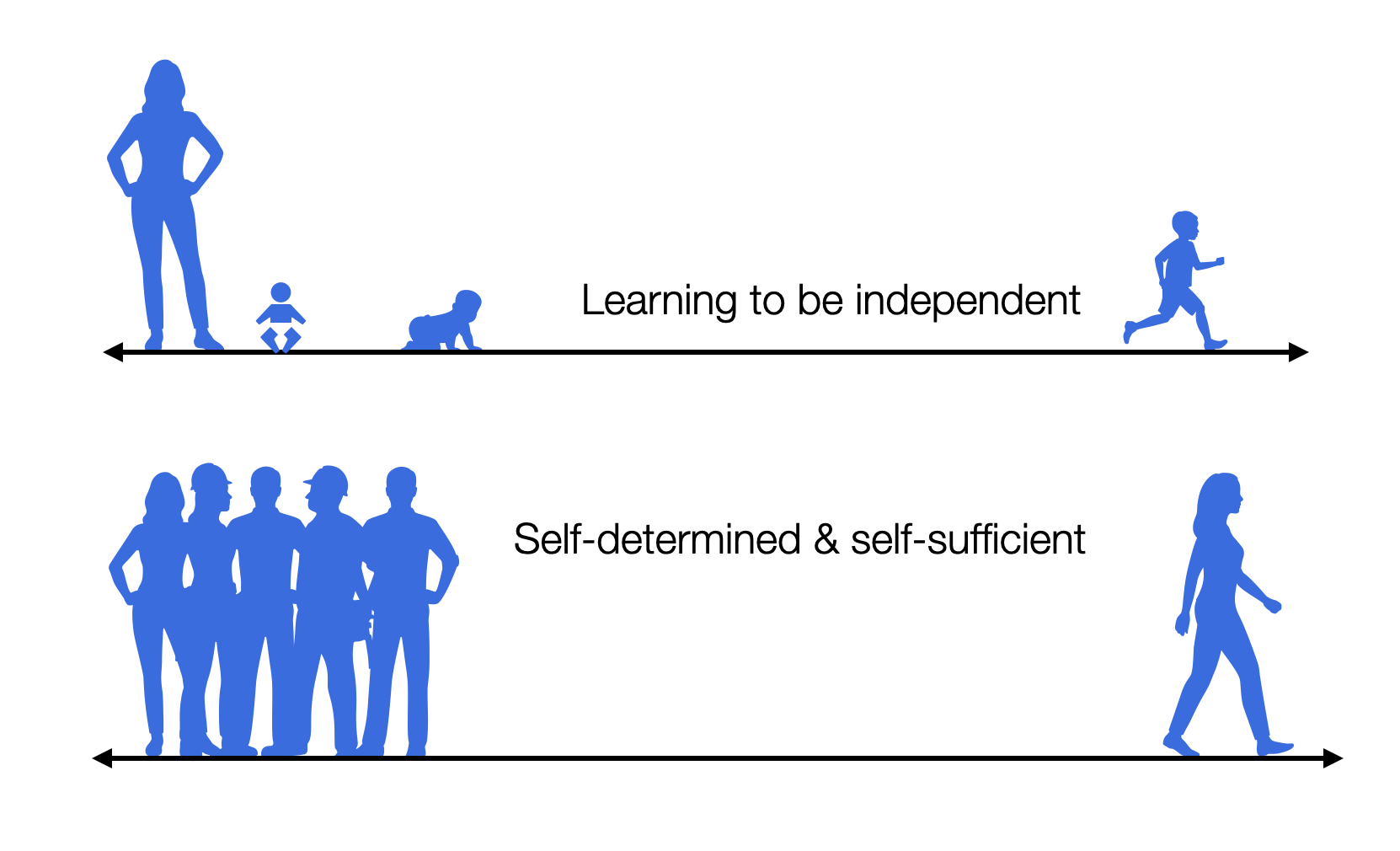

In the polyvagal perspective, safety is achieved through social interaction. We think this is fair, but it doesn't cover the whole picture. The diagram below shows how a child is completely dependent on its mother (or caregiver). Around the age of eight months, as he discovers the limits of symbiosis, anxiety begins to appear. He may have panic attacks (distress calls). He begins to walk between 12 and 18 months — a period of ambivalence between dependence and independence. At 24 months (the “terrible twos”), the child discovers the power to run away, explore the world around him, and return to his mother (sometimes turning around). When the caregiver encourages this freedom, the child gains confidence. He can be himself without losing the love of the group. Discovering his motor skills through games, fights, and intense activities is an important way to feel safe. It's the beginning of another sense of safety: I'm safe because I'm strong, smart, or skilled.

Later, as an adult, this person will learn to have his or her own opinions. They can spend time alone and withstand losses with resilience. Yes, the group is essential, but it's not enough. You must face loneliness and learn to be your best friend to survive. The PVT sees no safety outside the group. However, ignoring the value of a sympathetic tone and associating immobility with fear dramatically limits the pool of accessible resources. Safety comes from choosing the best action in each situation: sometimes fighting or running to let off steam, sometimes withdrawing, hiding, or giving in to fatigue. Maintaining agency is critical to preserving our power to act and shape our destiny as we navigate toward goals our surroundings may not approve of. Safety is knowing that we can resist and surrender in our own time. We need both companionship and independence.

Social stress

Porges suggests that sociality is the best thing for human beings. But ask people what stresses them the most — besides poverty, hunger, and taxes. Wives will tell you about their husbands, teenagers about their parents, and men about their bosses. And don't forget the neighbors, colleagues, and mother-in-law. It's also surprising that Porges ignores what psychologists call “angry faces. Faces can indeed be very frightening, threatening, and depressing.

A few weeks after 9/11, some New Yorkers began wearing T-shirts that read, “Stop talking to me about 9/11! Meeting others or working in a collective space is stressful for many people. They recover in solitude. Despite the modern trend toward teamwork, excellent results can still be achieved in solo missions.

2.8.16

Sex from a Polyvagal Perspective

Sex and the Monogamy Switch

Porges' work contains a few descriptions of sexuality. In his desire to offer a unified theory, he describes sexuality so broadly that the reader doesn't know whether he's writing about cows, prairie voles, or modern men and women.

In Love: An Emergent Property of the Mammalian Autonomic Nervous System (1998), Porges offers a far-fetched account of sexuality. “Once a decision is made to become monogamous with a chosen partner, the individual can become immobilized without fear, and the nervous system becomes vulnerable to conditioned love. Alternatively, to protect oneself from monogamy, the monogamy switch can be disabled by mobilization strategies, even during sexual encounters.” What he's saying is that as long as the sex partners are in sympathetic mode (actively moving), they can't bond and become monogamous. For that, they — or at least the female — must dare to become immobile. But in the polyvagal world, immobility is by definition scary. DVC allows intimacy, provided there's enough oxytocin. Again, the PVT uses generalizations and ad populum fallacies (= everyone knows this). Some criticism is needed:

Porges lacks specificity when describing female sexual behavior during mating. When females hold still, it is simply to facilitate fertilization. This is not freezing with oxytocin.

In the polyvagal perspective, overactive or passionate sex is a hindrance to bonding and monogamy. Consequently, people should stop activating the sympathetic system by moving too much during sex — if they want to remain monogamous.

As noted elsewhere, the DVC is not the cause of immobilization, a somatic-muscular manifestation orchestrated primarily by the PAG (midbrain) and the amygdala.

Endorphins, cannabinoids, and dopamine, which produce pleasure, are not mentioned.

The dimension of sexual pleasure is missing. And yet, as we know, not only humans but also primates (especially bonobos) and dolphins (see Evidence of a functional clitoris in dolphins, Brennan, 2022) enjoy sexual pleasure outside the reproductive function.

In Polyvagal Safety (2021, p.14 and 262), Porges explains the multiple pathologies some women present after sexual abuse as a return to a specific phylogenetic state linked to the dramatic experience of immobilization during the abuse. He ignores the helplessness phenomenon and brings it all back to the DVC.

In The Role of Social Engagement in Attachment and Bonding (Carter, 2005, pp. 33-54), Porges builds the case for immobilization during mammalian coitus. He misquotes an article by Leite-Panissi (2003) that doesn't mention the DVC. Without transition, he states that the vlPAG - responsible for immobilization behavior in the midbrain — “communicates” with the DVC, while the lPAG and dlPAG communicate with the sympathetic nervous system. This juxtaposition leads the reader to believe that Leite-Panissi supports Porges' hypothesis. Furthermore, we didn't find any confirmation that fear bradycardia (Battaglia, 2023)(Kotajima, 2016)(Szeska, 2015) is produced by the dorsal vagal branch.

In the same article, Porges writes that« in most mammals, lordosis involves the female immobilizing in a crouching posture with her hind end available for copulation.» Citing Daniels (1999), he emphasizes the role of the ventrolateral PAG (vlPAG) in immobilization in the face of threat. The fact is that only a few mammals - e.g., cats, rodents, and elephants — exhibit lordosis behavior. Primates, humans and marine mammals don't. According to Daniels, “the identity of a lordosis-relevant column in the PAG remains controversial. Furthermore, Daniels clarifies that the vlPAG is only one link in a long chain that runs from the prefrontal cortex to the spine through the hypothalamus, the PAG, and the pons. The following equation — female immobility during copulation = anxiety = vlPAG - is an attribution fallacy.

Are love and sex the same thing?

In chapter one, we saw that Sue Carter was the director of the Kinsey Institute and how Savage reacted to her appointment. He claimed that Carter was moving the institute away from its original mission-a scientific description of human sexual behavior, a watered-down version of sexuality, namely love, which is a cultural phenomenon. Mating is not specific to mammals—many mammalian species bond only at the time of mating. Birds are notorious for bonding. Parakeets respond to separation with intense mourning behavior.

Sue Carter is a leading specialist on oxytocin, challenged only by Dr. Kerstin Uvnäs-Moberg, author of The Oxytocin Factor (Moberg, 2003).

-

If we try to describe sexuality, with or without love, we can typically identify three steps in human mutually consenting sexual intercourse.

1. Meeting and establishing rapport: This phase may be accompanied by tenderness (e.g., words, caresses, or kisses), arousal, or passion. Sympathetic and parasympathetic systems may dominate during this stage.

2. The subsequent act — copulation — is a physical activity that may vary from quasi-immobility (of one or both partners) to intense physical engagement (locomotor, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems). The sympathetic system may dominate — rapid heartbeat, deep breathing, and sweating. “Making love” is then close to a passionate fight or an athletic activity.

3. After the sexual tension is released (e.g., by the sympathetic-driven orgasm), the partners may experience a state of pleasant parasympathetic rest.

In this three-phase act, various substances such as oxytocin, adrenaline, dopamine, and endogenous opioids play a crucial role in providing bonding, pleasure, and passion.

>> to the next chapter Heart Rate Variability