2.3.0

Polyvagal Hierarchical Perspective

In this chapter, we'll see how Porges' hierarchical model leads him to make several assumptions inconsistent with modern biology.

The Ladder Model

Not old, not primitive, but highly conserved

Homology

Reptiles are not our Ancestors

Phylogeny of the VVC

Compared Anatomy (Primitive vs. Conserved).

Universal Blueprint

Nature vs. Culture

The Primitive and the Savage

Anthropocentrism

Further reading

2.3.1

The Ladder Model

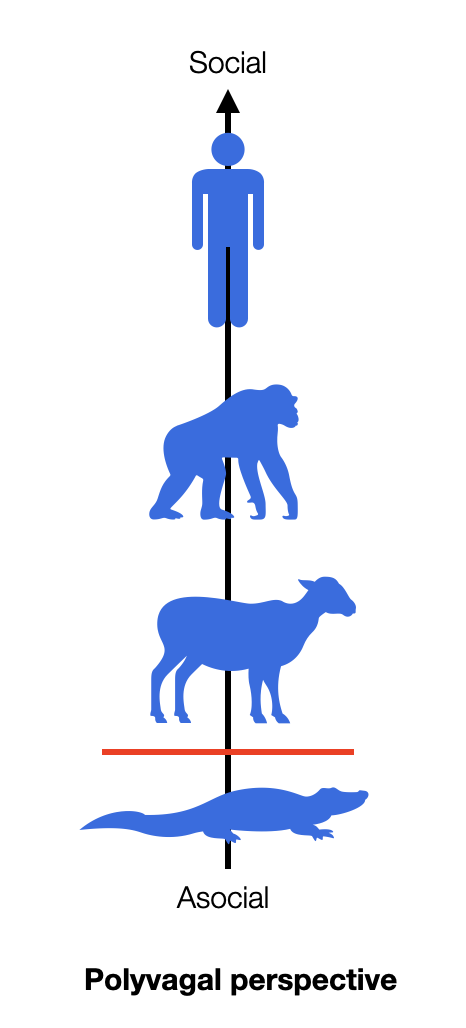

Following the concepts MacLean (Triune Brain) presented, the Polyvagal Theory perpetuates the medieval ladder model (Scala Naturae). In his work, Porges repeatedly describes hierarchical models (phylogenetic, ontogenetic, and more) that he tries to link. In this section, we will explore the fallacies in each ladder model and the delusion in trying to pair or synchronize these “temporal sliders.”

The different ladders that Porges presents are related to very different time scales.

The phylogenetic ladder represents millions of years, e.g., from the first vertebrates to the primates.

If we exclude the period of growth from newborn to adult, the human ontogenetic ladder covers a mere nine months.

The physiological, behavioral, and psychological ladders are based on minutes, seconds, or milliseconds.

Postulating that these ladders are synchronized — as Dana Deb explicitly puts it in The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy (2018, first section) — is quite a leap! Let's describe these ladders one by one.

a. Phylogeny (e.g., vertebrates or mammals)

b. Ontogeny (e.g., embryonic and fetal development)

c. Anatomy (e.g., brainstem)

d. Neuropathology (e.g., Jacksonian dissolution)

e. Physiology (three stages of autonomic activity)

f. Behavior (three types of activity)

a. Phylogeny

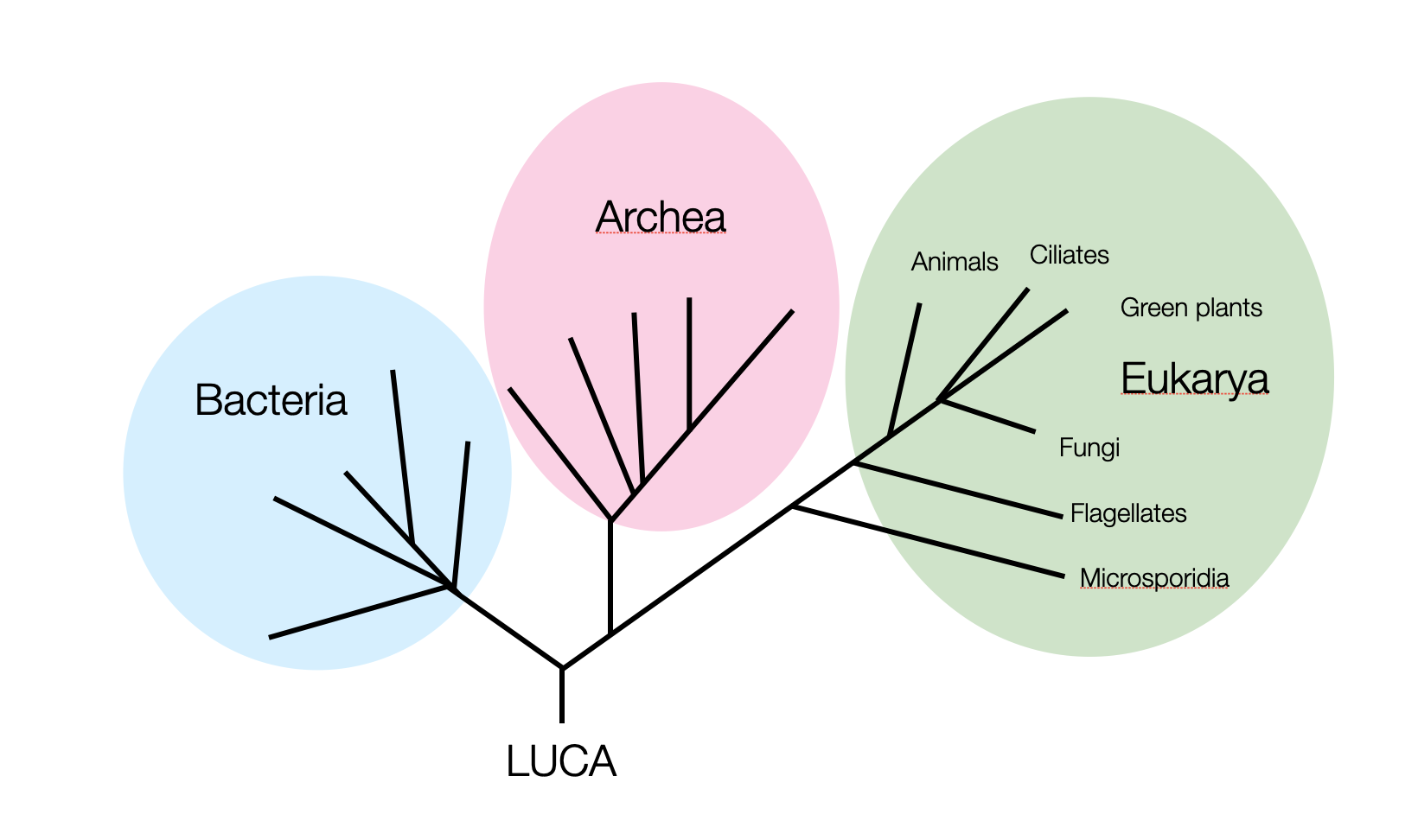

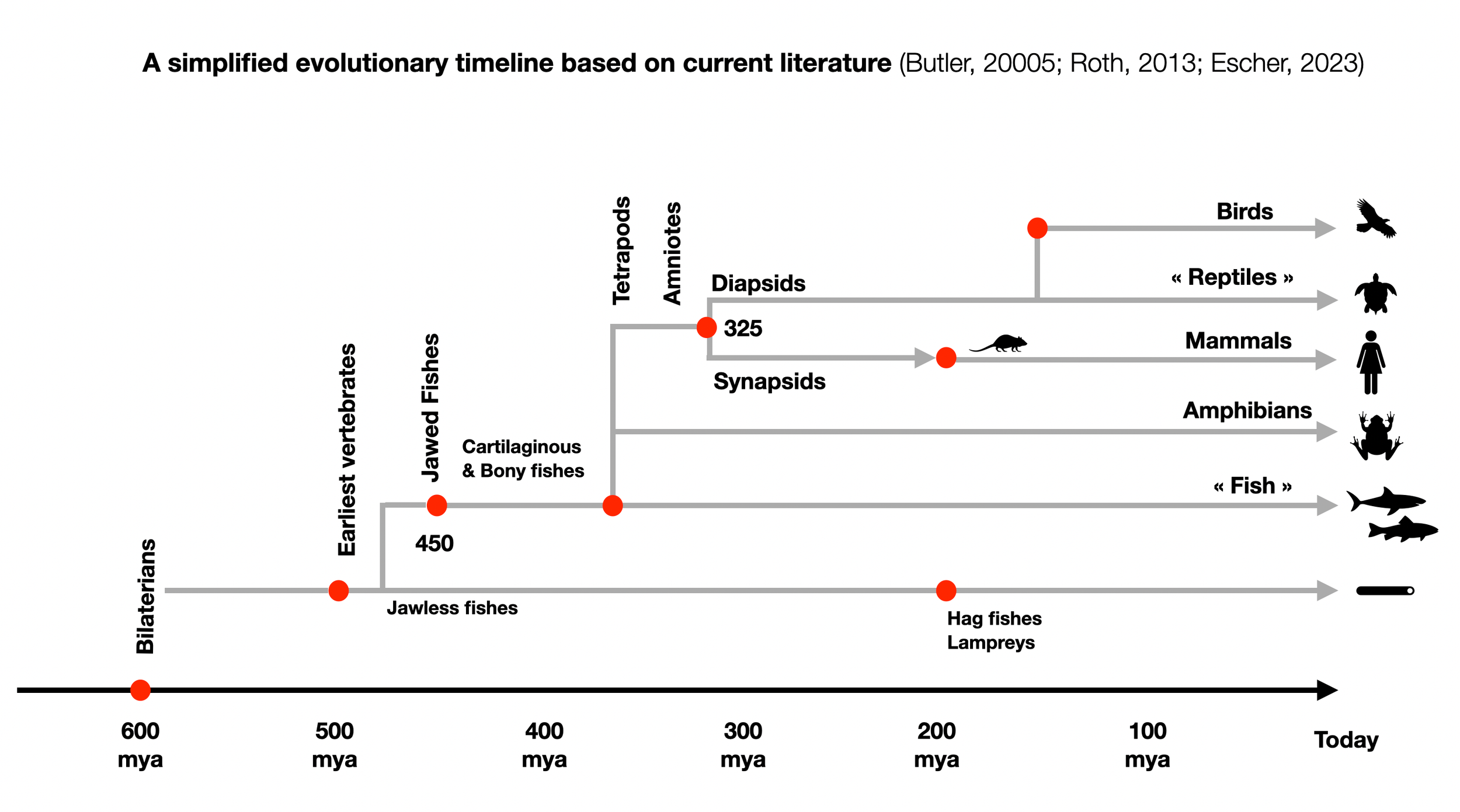

Phylogeny describes the evolution of a group of organisms, such as vertebrates or mammals. Challenging the old model of the Scala Naturae, Darwin sketched a coral form in 1837 that suggested branching rather than a single continuous path. In “On the Origin of Species” (1859), he used the metaphor of the tree of life:

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth.

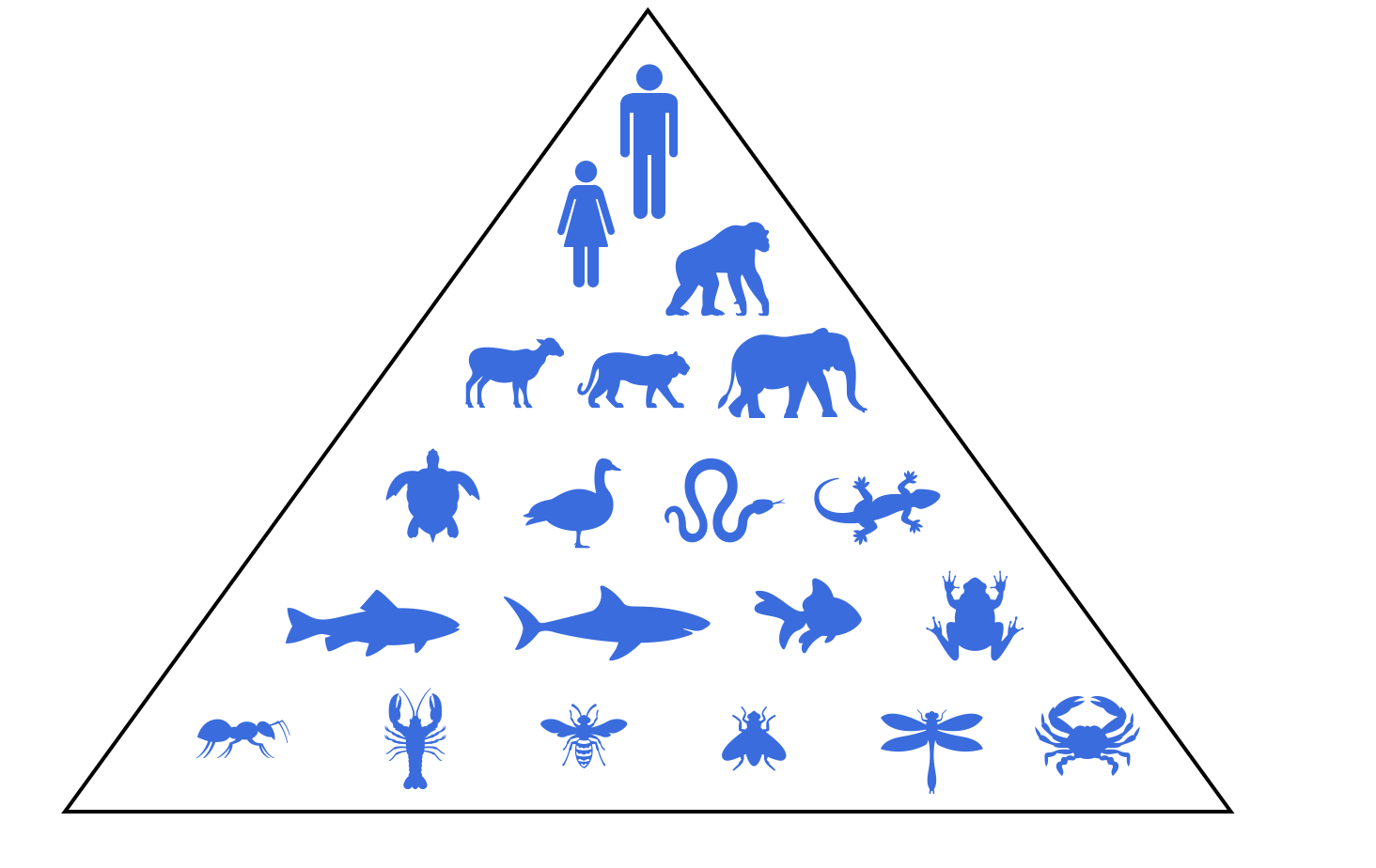

As we now know, life on Earth began more than 4 billion years ago. Instead of following a ladder form of evolution, it took the form of a rake or a comb. This calls into question the idea of a universal chain of beings extending without interruption from the atom to the highest angel (Bonnet, 1764).

In comparing mammals to reptiles, Porges makes three errors:

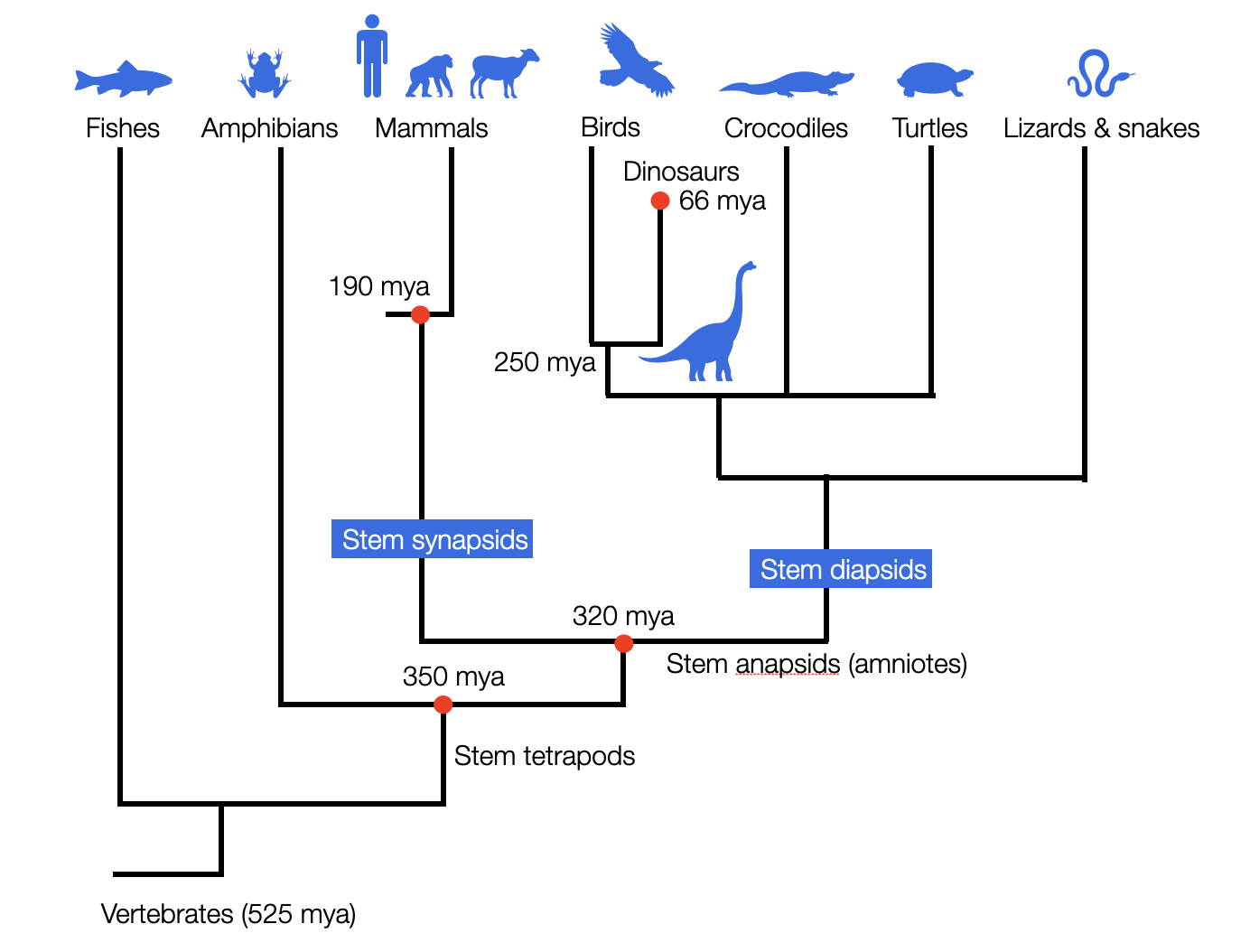

First, his phylogenetic model excludes fish, amphibians, and birds. He has chosen a group of animals that have been stigmatized since antiquity as mostly evil, asocial, and dangerous.

Second, he ignores that, according to modern biology, evolution is not a direct highway from single-celled forms to Homo sapiens. This road is more like a maze, representing myriads of different variations (mutations) that may or may not lead to present life forms.

Third, he tends to ascribe to the entire group of mammals qualities that qualify them as modern Homo sapiens, that is, shaped by thousands of years of culture. However, Homo sapiens, which appeared only 0.3 mya (million years ago), is one of 6400 species of mammals. The mammalian path, splitting from the future “reptiles,” began 320 mya. While humans are mostly very social creatures and breathe regularly, many mammals live solitary lives or are long-term divers. Similarly, while humans extensively use face and voice — but not only — to communicate, other mammals use global body language and scent. The PVT is an anthropocentric perspective.

Schematic representation of the three domains of life. Scientists estimate that LUCA (the Last Common Ancestor) was around 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago (©absb, 2024).

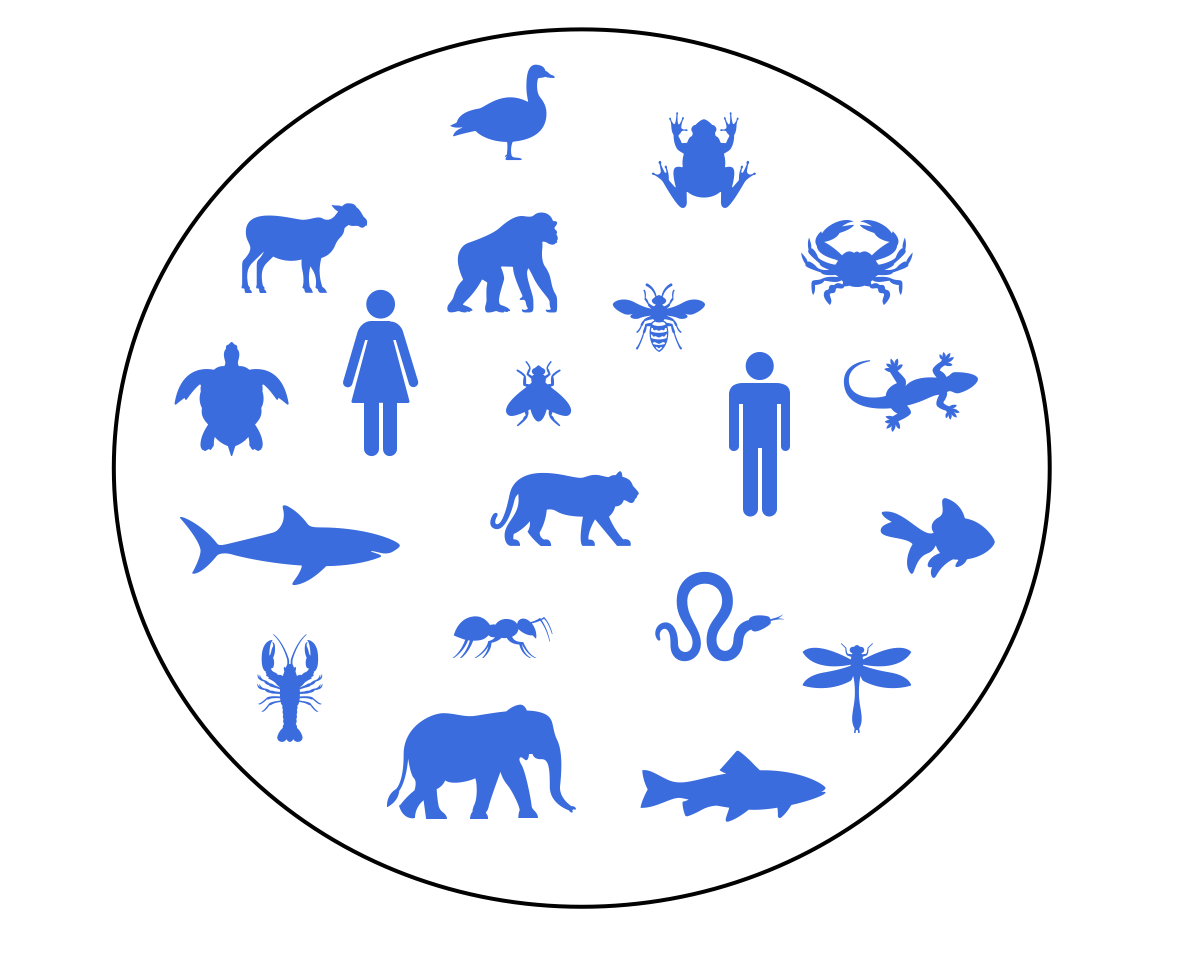

Cladistic perspective: This simplified diagram shows how the two lineages leading to “reptiles” and mammals separated about 320 million years ago. In this cladistic perspective, in contrast to the hierarchical ladder model, all existing species are placed on the same finish line since they have all survived to the present day (©absb, 2024).

Monophyletic perspective

This diagram shows the hierarchical model of the Scala Naturae as proposed by Aristotle and later adopted by the monotheistic religions. It sees creation as a monophyletic ascent from the simple to the complex. Darwin, however, had a polyphyletic vision. Modern evolutionary biology, especially the cladistic perspective, has vindicated him, for evolution shows how multiple living things successively evolve (mutations) and select (natural selection) new traits to adapt to their ecological niches. These processes often occur in parallel, as convergent evolution, in separate, unrelated clades. Wings in birds and bats or endothermy in birds and mammals are some examples. A strict unidirectional ladder model makes it difficult to understand how evolutionary acquisitions (e.g., myelination, sociality, language, diving reflex, fur, and migration from sea to land or back to sea) result in separate lineages (clades)(@absb, 2024).

b. Ontogeny

It describes the development of an organism from the fertilization of the egg to the adult.

Recapitulation

In the groundbreaking Ontogeny and Phylogeny, renowned biologist Stephen Gould devotes the first 200 pages to recapitulation. Based on the work of Meckel and Serres, recapitulation (Wikipedia) is best expressed through Haeckel's words: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” According to Harvey (1653), in the first days of life, “the egg begins to step from the life of a plant to that of an animal.” Later, all the steps of evolution are repeated until the final form — e.g., a human baby — is obtained. Although science later rejected the concept, it's still in the air. More on Recapitulation in Part “Ontogeny and Phylogeny?”

Although Porges clouds the idea of recapitulation with complex sentences, the synchronization of phylogeny with ontogeny, he suggests, is a form of recapitulation. Behavioral dissolution, following Jackson, is a reverse recapitulation.

In The Early Development of the Autonomic Nervous System Provides a Neural Platform for Social Behavior (Porges 2011, p.8), Porges writes:

“The development of the autonomic nervous system in the human fetus mirrors the broader phylogenetic progression described above. The oldest existing autonomic system, comprised of unmyelinated vagal fibers originating from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX), is also, embryologically, the earliest system to develop in utero.”

Although Porges takes the trouble to cite various sources (Cheng, 2004), (Nara, 1991), (Brown, 1990) to support his thesis, the argumentation is not convincing. After reviewing these articles and some more recent ones (Cheng, 2005, 2006, 2008), (Paxinos, 2012)(and Ashwell, 2012), Porges' claim seems unproven. Here are a few reasons:

First, since the authors describe the evolution of the nucleus ambiguus without distinguishing between branchiomotor and external formation, we cannot know how the ventral parasympathetic part developed.

Secondly, Porges makes no distinction between the appearance of the parasympathetic neurons, their migration, their extension to the periphery and their myelination — four different processes. It's clear that the process of myelination, like that of the other branchiomotor nerves (V, VII, IX), takes time and can last until birth and beyond (Hatta, 2007). The statement that the DMNX is the “earliest” system to develop is undifferentiated.

Prenatal development of the human nucleus ambiguus during embryonic and early fetal periods (Brown, 1990), cited by Porges, describes the first migration of neuroblasts (stem cells) in 4-6 week embryos toward the medial motor column. The following migration is to a position near the DMVN at 6.5 weeks and finally to the ventrolateral position at 7 weeks. By 9 weeks, a nearly adult organization is evident. The number of mature neurons gradually increases until 12.5 weeks.

According to Development of the peptidergic innervation of the human heart (Gordon, 1993), based on several sources, parasympathetic and intrinsic innervation of the heart precede sympathetic innervation in most mammals, including humans. In addition, other factors come into play early (neuropeptides) that Porges doesn't consider.

A parasympathetic activity is established around 20 weeks GA during pregnancy and matures rapidly by 30 weeks (Zwanenburg, 2021), and fetal HRV (fHRV) becomes measurable. It appears that ventral cardiac neurons are active long before complete myelination.

According to Cheng (2004), myelination of the vagus nerve begins between 14 and 17 weeks of development or earlier. However, the first swallowing reflex (NAmb) appears at 13 weeks. The NAmb contributes axons to the thoracic vagus nerve as early as 13 weeks of gestation. Full development of the DVMN (dorsal vagal motor nucleus) takes the same time. The connection to the NTS is not well-developed until the 24th week of pregnancy and cannot be adequately discussed.

Porges' argument would be correct if he were comparing two identical structures. However, the DMVN and the NAmb have radically different functions. Since the mammalian dorsal parasympathetic (DMVN) has, so to speak, outsourced its cardiac vagal neurons, its tasks are mostly subdiaphragmatic (e.g., digestion and metabolism). The embryo's heartbeat remains rapid until birth. Gradually, as the myelination of the ventral parasympathetic branch progresses, the heartbeat slows down.

There are two more articles to consider: Establishment of vagal sensorimotor circuits during fetal development in rats (Rinaman, 1993. p. 651) describes how, in rat embryos, the first motor neurons are seen in the NA region at E13 (embryonic day), as well as neurons in the dorsal region that migrate toward the NA. Labeled DVMN motoneurons are first seen at E14. The migration of NA neurons appears to continue after their axons have projected peripherally. NA motoneurons complete their migration between E15 and E16. NA motor axons enter the peripheral gastric field before DMVN motor axons.

Development of gut vagal innervation: guidance of the migrating nerve (Ratcliffe, 2011).

c. Anatomy

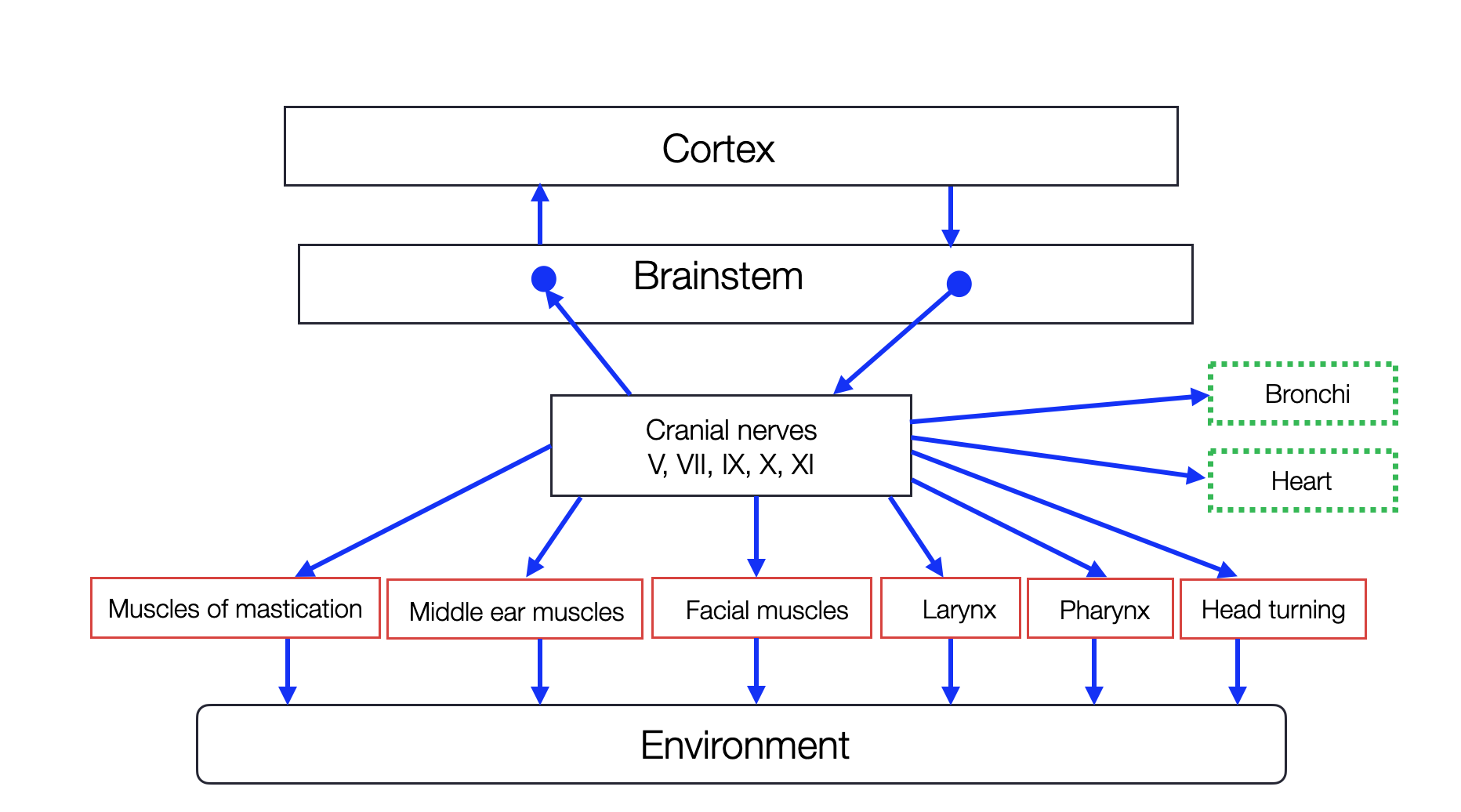

Polyvagal Model

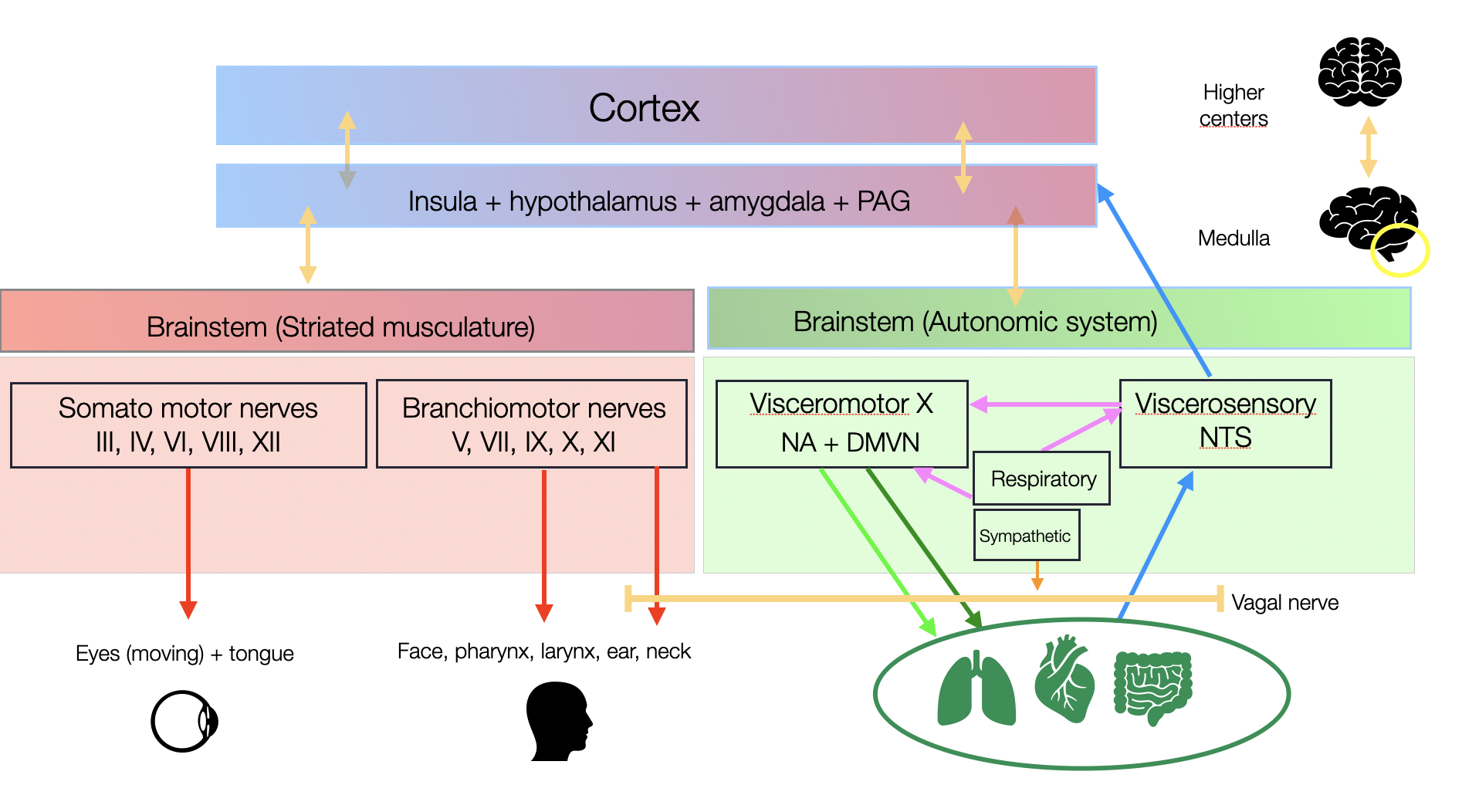

Porges proposes a schematic graphic representation of the ventral vagal complex. We doubt that any reader — except anatomists — knows the medulla's topography (the brain stem's lowest part). One might find a modern neuroscience book with colorful two-dimensional graphics. However, the brain is three-dimensional; unfortunately, most textbooks contain errors. Porges' “anatomical ladder” is more of a construct of the mind, postulating neural connections between different centers (e.g., cranial nerves V, VII, IX, and X) without sufficient evidence. It ignores other, more essential connections (e.g., between the NAmb and the NTS or respiratory centers). The portrayal of the DVMN (or the entire DVC) as a rudimentary relic is misleading — probably the most glaring misconception in the PVT.

Polyvagal Model

(redrawn and modified, based on Porges, 2012; ©absb)

Orthovagal Model

The apparent proximity of the branchiomotor nuclei (V, VII, IX, and X) is misleading. In the literature, we found no evidence of direct local connections between these nuclei. The new diagram highlights the functional disparity: one side representing the somatomotor component (striated muscles), the other, the visceromotor component (modulating cardiorespiratory functions). The nucleus ambiguus (NA) contains both types of nuclei, reminiscent of the divided sovereignty of Cyprus in the Mediterranean. Notably, we found no evidence of direct connections between the four regions of the NA. Conversely, the external formation (NAext), which originates the ventral parasympathetic pathway, is strongly connected to the NTS (nucleus tractus solitarius), the central hub for visceral functions.

Orthovagal Model

©absb, 2024

d. Neuropathology

The next ladder is downward — from a healthy to a pathological brain. Indeed, accidents (e.g., contusions, strokes, or epilepsy) can impair higher functions (as in the famous case of Phillips Gage) and disinhibit lower levels of the brain. Good manners may be gone. But to believe that any cortical tumor or lesion will set the savage free is naive. On the contrary, cortical inhibition (e.g., alcohol or drugs) can allow subcortical regions to unleash creativity — as in theatrical improvisation, automatic writing, or free jazz. Often, a lesion at a deeper level-subcortical or in the brainstem can cause problems. In this case, there is no Jacksonian resolution. The belief that the best of us (education and morality) resides in the “higher” parts of our brains is outdated. It smacks of colonialism. Frontal lobes can plan anything. Peace or war. Hospital or death camp.

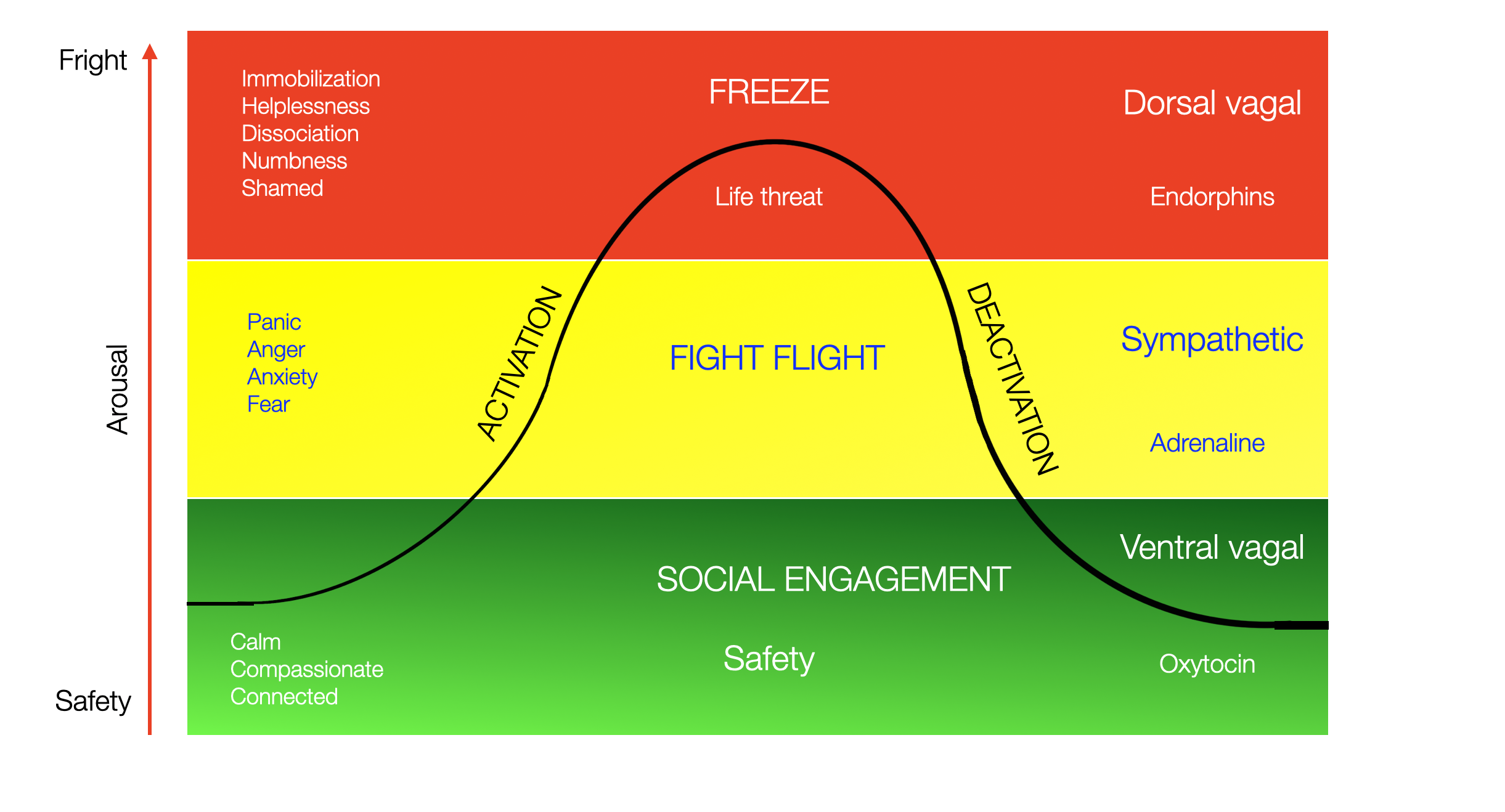

e. Physiology

The PVT describes how three physiological states overlap with specific emotions and behaviors. The ladder here is no longer temporal (as in phylogeny and ontogeny) but refers to a scale of threat: safe to lethal. Porges uses a color code to mark three psychological domains, from green (safe) to yellow (stress, alarm) to red (inescapable situation). The “green” ventral state is experienced in a safe interaction (e.g., positive mother-infant interaction), the “yellow” sympathetic state is a fight-flight situation, and the “red” dorsal state is qualified by immobility, fear, metabolic shutdown, and dissociation.

This is a typical “polyvagal chart” illustrating the curb of activation-deactivation. Using the red color for freezing is somehow counterintuitive!

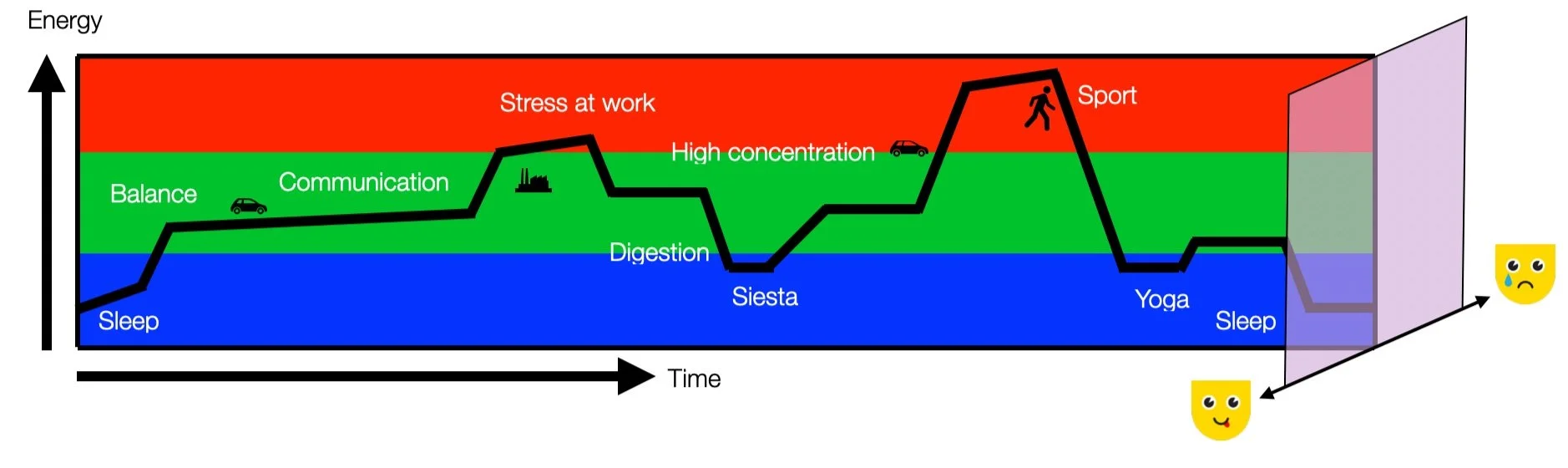

An energetic perspective

Instead, we propose a 3D model that integrates the three physiological domains from a non-pathological and non-hierarchical perspective. In a later chapter, we will present a more detailed diagram representing a typical day with three physiological energy domains. Energy and time are the first two coordinates (X and Y). The positive (pleasant) and negative (unpleasant) values are represented by the depth (Z). More about this topic under “What else?”

In the 'ventral, sympathetic, and dorsal' hierarchical model, Porges links three behaviors (social engagement, energetic movement, and immobility) to three autonomic functions. However, this model is not without its limitations. It applies a robust predator-prey model to standard autonomic functions (regulation, activation, and rest), which may not fully capture the complexity of these functions. It also blurs the line between physiology and psychotraumatology (or pathology), potentially limiting our understanding. Let's not explain the hills through Mount Everest. In light of these limitations, it's important to consider alternative perspectives that may provide a more comprehensive understanding of these phenomena. Moreover, the qualification of the 'dorsal' zone as a place of maximum threat is highly inconsistent with our current scientific knowledge, further highlighting the need for alternative viewpoints.

The ventral vagal branch (nucleus ambiguus) regulates most parasympathetic activity above the diaphragm. It slows down the heartbeat, including during deep diving by marine and terrestrial mammals (see “Diving Reflex” in the chapter “Shutting Down”). This reflex reduces the amount of energy expended. Birds, without even a “belly”, are highly social animals.

The sympathetic system is not limited to threatening situations. It intervenes when we stand up (orthostatic reflex), are excited, or are “physically engaged,” such as dancing, running, or making love. This sympathetic activation is not regression.

The dorsal vagal branch (DMVN) protects the heart and is anti-inflammatory. It regulates appetite and the digestive system. Since it is not connected to the motor system, it doesn't cause immobilization—this is the PAG in the midbrain. It also has no role in depression and dissociation, which are independent neurobiological systems.

The three rows of photos above represent diverse types of activities.

The first row shows socially engaged—some happy, others not.

In the second row, people are engaged in a physical activity. The surgeon, who doesn’t run, is highly concentrated – thanks to noradrenaline.

In the last row, four people and one dog are still – some with eyes closed —alone, contemplating and resting. No fear.

2.3.2

Not old, not primitive, but conserved

If we compare texts on evolution written 50 years ago with those written in the last decade, we find that the terms “old” and “primitive” have practically disappeared. Instead, authors speak of “ancient” and even more often of “conserved.” Think about it: would you say that the steering wheel of your — supposedly — new Tesla? While the “old” Tourer Ford-T4 (1924) already had a wheel? Certainly not. The most frontal part of the brain — the telencephalon — as “old” as the hindbrain. What has changed is the volume of the neocortex.

The VVC (ventral vagal complex) doesn't replace the DVC (dorsal vagal complex), which makes it “old.” The cardiac vagal neurons that migrated to the respiratory centers retained the same function: to slow the heart. Its fibers' myelination makes it more efficient, and its optimal position is close to the ventral respiratory group. However, the dorsal vagal complex continues to perform many vital functions (e.g., protecting the heart, promoting digestion, and regulating the immune system) that are the opposite of the “old” functions.

It is incorrect to say that vagal innervation of the heart precedes sympathetic innervation. According to Taylor et al. (2014), the heart of the first vertebrates is not innervated. The heart of the lamprey, however, has an initial vagal (cholinergic) innervation that, when stimulated, accelerates the heart (Taylor, 1992). It is a transition from hormonal heart control to neural heart control.

Take the wheel: different looks, different ages, but still the same structure — hub, spokes, and circle — and the same function — to roll. Identical to the steering wheel. No one would say that a wheel, or a steering wheel, is old — or primitive. Similarly, evolution has conserved patterns of organization (e.g., tripartite brain), molecules (e.g., enzymes, neurotransmitters), and genetic pools (e.g., homeobox). Thus, we can study human sleep mechanisms in the fruit fly (Drosophila) or immobilization in the zebrafish.

2.3.3

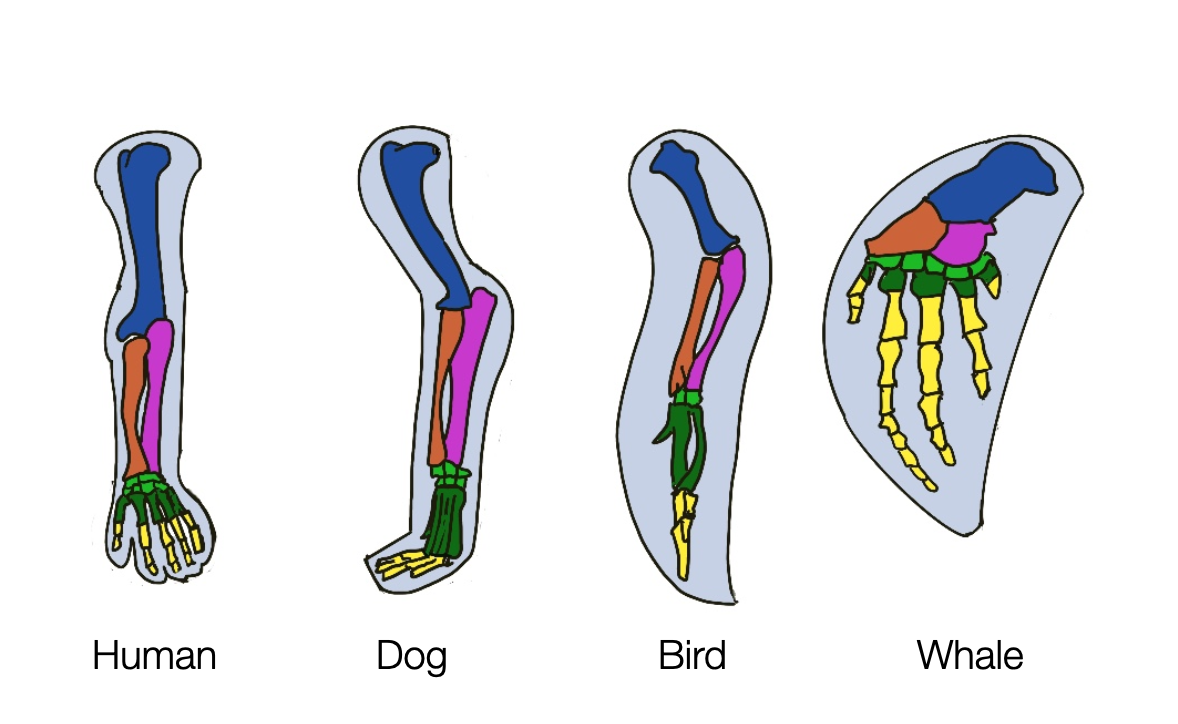

The homology principle contradicts the Polyval Theory

We speak of homology when two species descended from a common evolutionary ancestor show similarity in structure, physiology, or development. The limbs of humans, cats, whales, and bats are excellent examples of homology. Whether it is an arm, a leg, a fin, or a wing, these structures are based on the same bone structure.

(Greek ομειοσ homeios = similar, as in homogenous, homonym, or homosexual). The concept of homology is crucial to understanding why the hierarchical perspective proposed by MacLean and Porges doesn't fit modern biology. Even Aristotle and medieval scientists began to compare the anatomy of different species. In the early 19th century, Sir Richard Owen, a British anatomist and paleontologist, introduced the concept of homology: “the same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function.”

Homology and Research

Because there are so many homologies between simpler animal models (fruit flies and zebrafish), modern research uses fewer mammals (e.g., mice, rats, and cats). Instead, two models have become very popular in neuroscience: the zebrafish and the fruit fly (Drosophila). They allow the study of neural circuits of immobilization (freezing) and neural computation. The fruit fly brain has only 135,000 neurons instead of our 86 billion neurons, so genetic research is much easier.

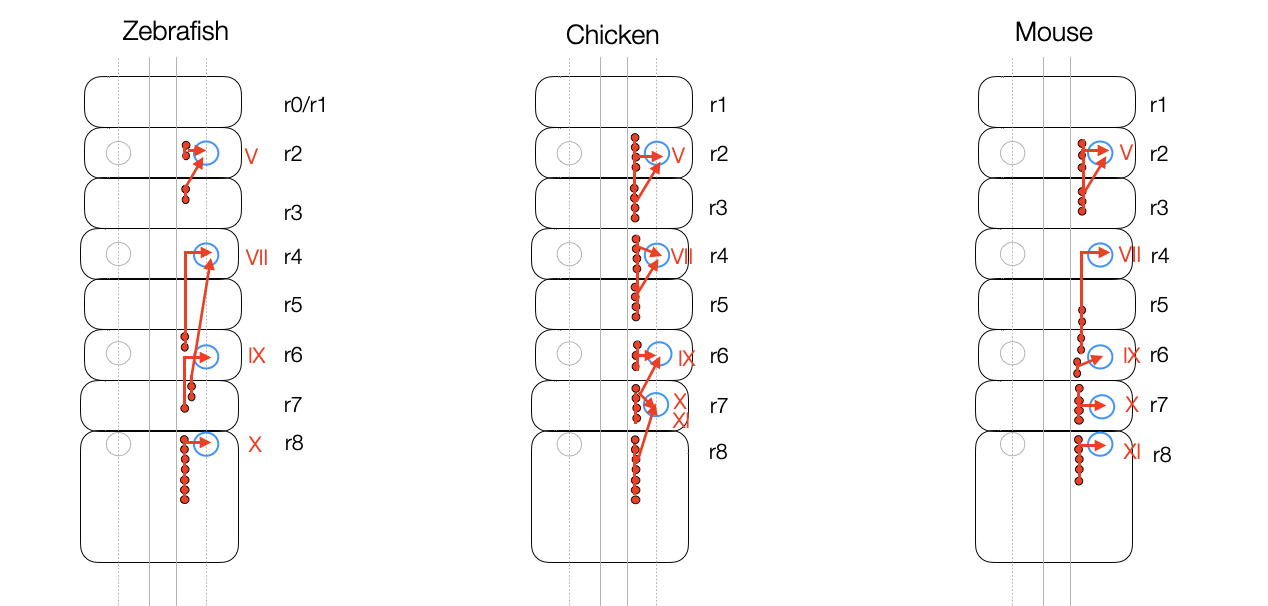

Simplified representation of the branchiomotor neurons in the hindbrain (rhombomeres 0-8), based on Fig. 1 in Chandrasekhar (2004). All vertebrates form homologous cranial nerves (V, VII, IX, X) and muscles allowing basic movements (e.g., capturing, chewing, and swallowing) (adaptation, ©absb, 2024).

The concept of homology has radically changed our view of brain evolution because scientists can show how different classes of animals (e.g., reptiles and birds vs. mammals) have taken different paths to develop super-brains. Therefore, the mammalian brain is not inherently better than the avian brain. We find similarities between the two groups.

With the advent of molecular biology in the 20th century, homology expanded beyond anatomical structures to include similarities at the molecular level, such as DNA sequences and proteins. In the second half of the 20th century, cladistics further refined the concept of homology by emphasizing the importance of identifying shared derived characters (synapomorphies) that indicate common ancestry.

The triune brain concept suggests that non-mammals lack superior cortical structures. However, modern anatomy has shown that “reptiles” and birds have evolved their brain variation; some birds have a reasoning power equivalent to primates — except for the genus Homo. Crabs are known for their cleverness. The concept of homology shifts the dialogue from a hierarchy of superior and inferior organisms to one that appreciates the diversity and adaptability of the anatomical structures of different species, including the brain. Understanding homology promotes a more nuanced and respectful view of animal life, recognizing that each species is adapted to its niche in unique and complex ways.

2.3.4

Are reptiles our ancestors, as Porges says ?

Unlike Aristotle, Porges uses a short evolutionary ladder, constantly comparing mammals to “reptiles,” leaving out of the discussion invertebrates, fish, amphibians, and birds, many of which are highly social and exhibit complex behaviors. In the most recent book (2023), Porges calls reptiles “our asocial ancestors.” These are three errors.

Reptiles are not our ancestors — neither are the “ancient, extinct reptiles.”

Approximately 350 million years ago, a key evolutionary split occurred among the stem tetrapods (from Greek, meaning 'four feet'). Unlike amphibians (e.g., frogs), which must lay their eggs in water, amniotes lay eggs with hard shells, allowing them to thrive independently of aquatic environments such as rivers, lakes, ponds, and swamps. Stem amniotes are sometimes called 'reptiliomorpha,' though this doesn't classify them as reptiles. For more information, see: Reptiliomorpha. Readers are encouraged to examine the cladograms at Sauropsida that illustrate the early divergence of pathways leading to modern reptiles and mammals.

Shortly after that, about 326 million years ago, another significant evolutionary split occurred between synapsids (the ancestors of mammals) and diapsids (the ancestors of “reptiles,” dinosaurs, and birds). A critical anatomical detail marks this divergence: openings in the temporal bone — none in anapsids, one in synapsids, and two in diapsids (Butler, 2005, pp. 80-82). Thus, reptiles are not the ancestors of mammals, contrary to Porges' repeated claims (Porges, 2023). Porges (2024, p. 11) insists in bold letters that his comparison of mammals and reptiles does not refer to modern reptiles, but to their ancestors (stem reptiles). This does little to change the fact that the last common ancestor of reptiles and mammals was an amniote — not a reptile. The notion of a “reptilian brain” (MacLean), which suggests ancient reptiles as our evolutionary predecessors, is inaccurate.

Reptiles don't represent all non-mammals

Porges creates an artificial construct by pitting social mammals against asocial “reptiles.” Regarding classification, “reptiles” is an artificial group — biologists call it a paraphyletic group — because the group of reptiles should include dinosaurs and birds. As we know, birds are very social animals, and their intelligence rivals that of primates. Moreover, the phylogenetic “predecessors” on the phylogenetic ladder are fish and amphibians, often more social than mammals. Why does the Polyvagal Theory leave them out? Reptiles Are Not Asocial

In Polyvagal Theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality (2021), Porges postulates that “evolution has repurposed the neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system to support sociality”. For him, there is evidence that the vagal system in mammals “has been repurposed to support and express sociality” (Porges et al., 2021). This concept, rejected by Grossman (2023), is scientifically incorrect in two ways. First, evolutionary theory doesn't welcome teleological claims. Even if domesticated mammals are somehow more social than “reptiles,” there is no original blueprint. Second, as we will see in the chapter “Social,” Many non-mammals, including invertebrates, lead highly social lives.

According to modern zoology–the study of living animals and a branch of biology–asocial reptiles are a myth, mainly due to a lack of careful study. In Breaking the Social-Nonsocial Dichotomy: A Role for Reptiles in the Study of Vertebrate Social Behavior? (2012), Doody describes how biases have distorted the study of reptiles. Most likely, Porges got his observations from the pet store. If we take the time to Google “social reptiles” or explore YouTube, we find countless examples of social reptiles. Of course, for some reptiles, amniotic development allowed them to lay eggs and leave them after a short time — for safety reasons. Humans think emotionally, but nature thinks economically. In retrospect, the reptilian way worked, as reptiles still exist today.

2.3.5

Phylogeny of the Nucleus Ambiguus

Extracting and dating bones from a billion-year-old animal is relatively easy. It is impossible to do the same with a soft structure unless fossilized. According to fossils, mammals appeared around 60 mya. Molecular biology puts them at 100 mya. However, the first mammals appeared at 326 mya. It is difficult to follow the evolution of smooth mammalian features such as breasts and fur.

Mammalian fur even disappeared in marine mammals. Therefore, the claim that ALL mammals and no other group have a “ventral vagal complex” (VVC) is impossible to verify. Many groups of mammals have disappeared during evolution.

At the very least, we should find in ALL modern mammals a complete migration of cardiac preganglionic vagal neurons (CPVN) from the dorsal to the ventral position (nucleus ambiguus) — parallel to a myelination of the ventral efferent fibers. This is not the case, because the migration and myelination of ventral vagal neurons doesn't follow an all-or-nothing principle. In the brainstem of modern mammals, some CNV are still dorsal, some are intermediate, and some are ventral (nucleus ambiguus) (Hopkins, 1998).

Moreover, some non-mammals — sharks, certain reptiles (Sanches, 2019), or primitive lungfish (Monteiro, 2018) — show myelination of the vagus efferent (without migration of dorsal cardiac neurons into the NA).

The claimed appearance of a “ventral vagal complex” as a new organ unique to mammals is problematic. It may sound intriguing and exciting, but it's a fallacy. Ninety percent of the elements that make up this fictional complex are present in non-mammals (cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, and XI). The only novelty is the migration of cardiac and respiratory vagal neurons (CVN and RVN) from a dorsal to a ventral position. The external formation (NAext) is now between the “old” compact nucleus ambiguus and the ventral respiratory column. In addition, these thin ventral parasympathetic B fibers are now myelinated, increasing transmission speed. However, in large animals such as sheep, we find dorsal fibers with the same velocity as ventral B fibers (Booth, 2021). Nothing is black and white here.

The claim that all mammals use the branchial apparatus (e.g., the face) as a primary communication interface, adding in the same breath that non-mammals don't communicate, is false.

2.3.6

Comparative Anatomy of the Brains

Open those impressive books on comparative anatomy (e.g., Nieuwenhuys, Butler & Hodos, or Kaas). You will be amazed at how vertebrates share the same gross scheme of organization. The only major exception is Homo erectus, and even more so Homo sapiens, because their brains showed an enormous increase in volume. But Sapiens is only one of 6,400 species of mammals.

Many still believe that “lower vertebrates” lack essential structures. Some write that “the brain stem is the oldest and innermost region of the brain,” as if there had been creatures in the distant past with only a brain stem for a brain. In The Long Evolution of Brains and Minds, Gerhard Roth (2013) describes how the evolution from a diffuse nerve network to a tripartite brain (forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain) took place long ago — about 600 mya. This was probably before the split between protostomes and deuterostomes (separation of mouth and anus). Our brains share many characteristics with chimpanzees, fruit flies, fish, and worms. Due to conserved genes (homeobox), most living complex animals share the exact basic blueprint. In addition, all vertebrates, from fish to mammals, have twelve cranial nerves (some even more) — including a nucleus ambiguus (or its homolog). Reading about zoology (e.g., fish, birds, and reptiles) and biology will make the reader aware of the connections between all living beings.

Beautiful diversity – so many expressions of life, still so many shared qualities! (Free adaptation of Butler & Hodos cover, 2005).

2.3.7

Life’s Universal Vertebral Blueprint

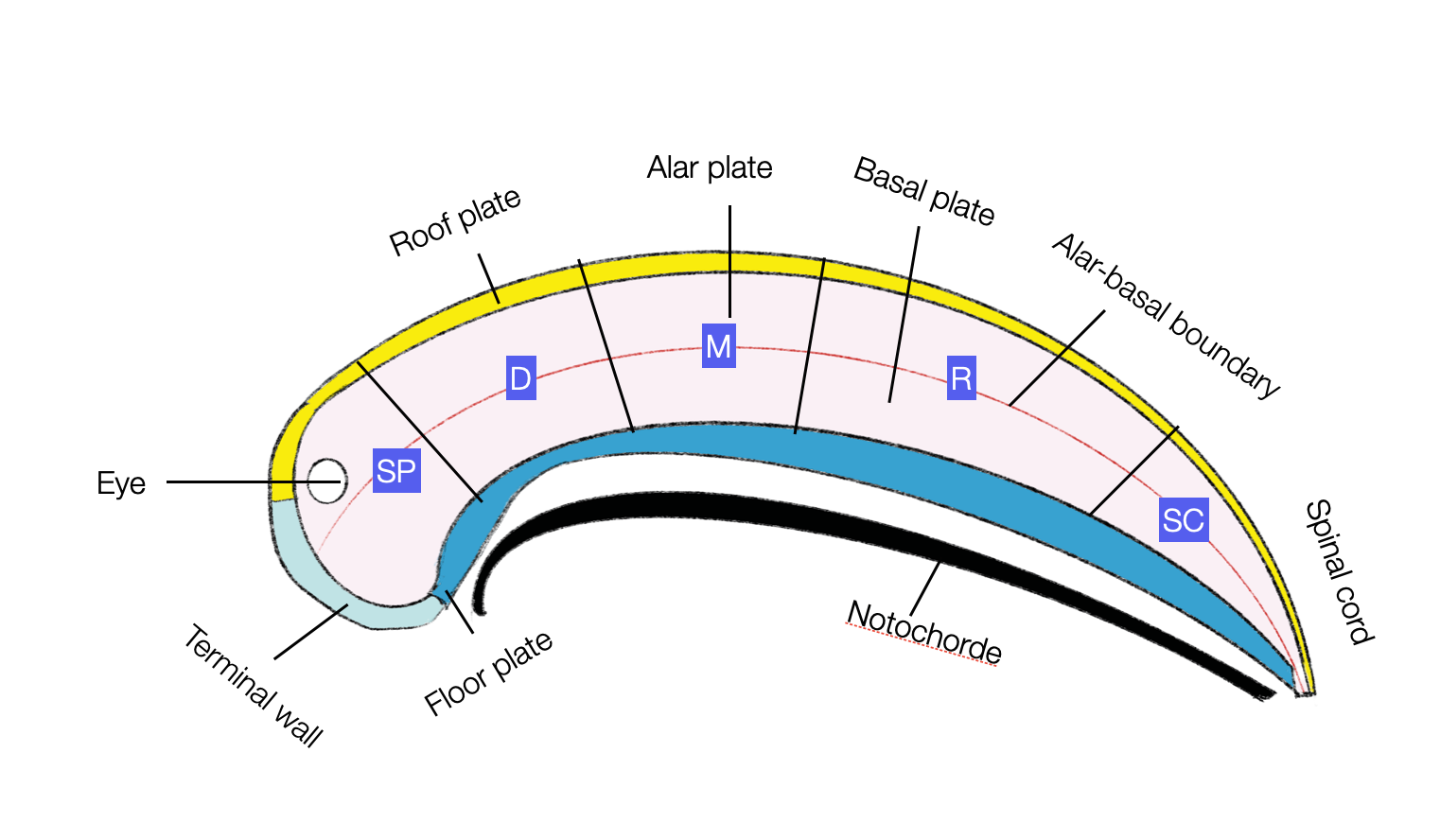

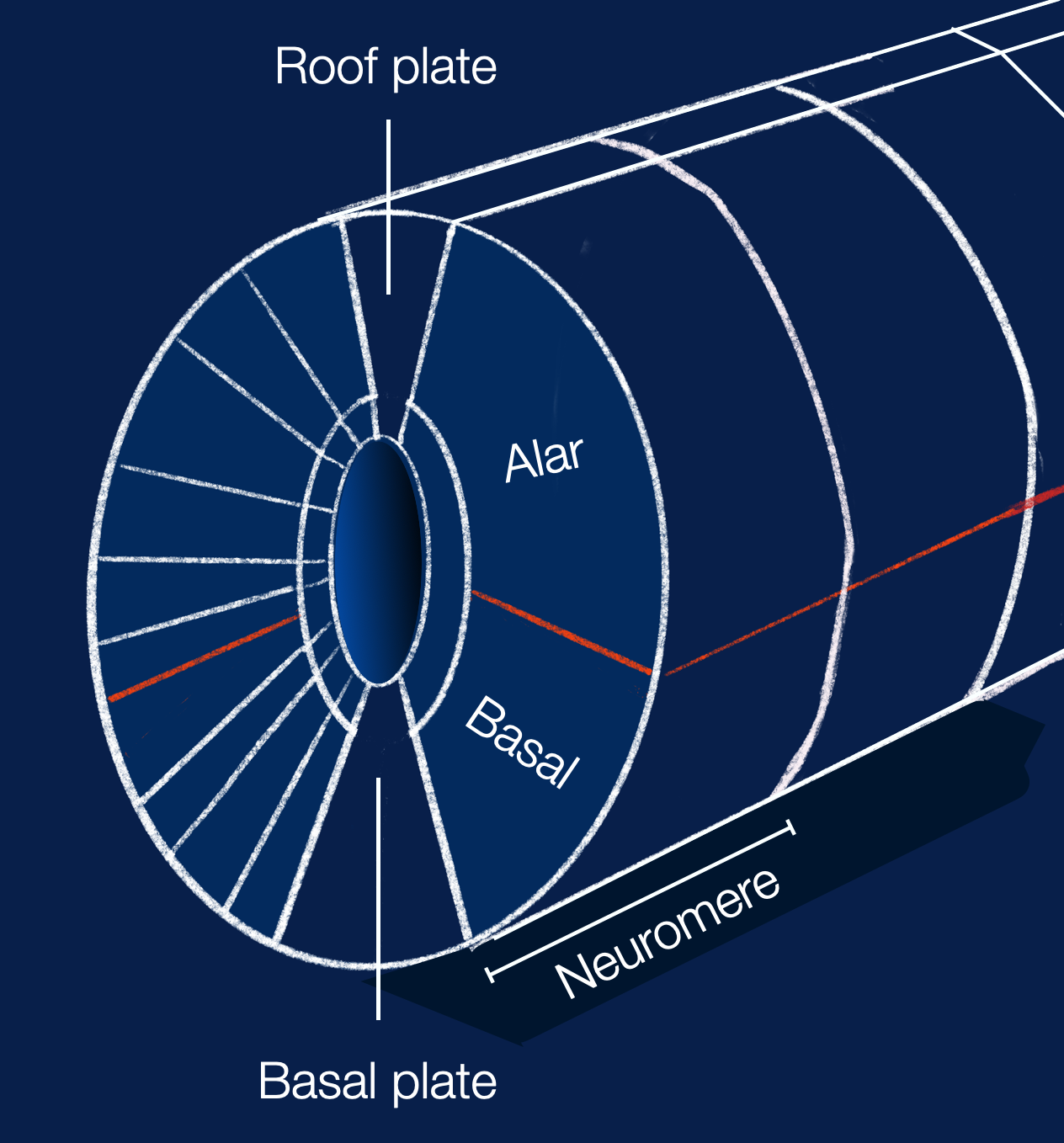

All vertebrates present a similar early embryonic organization of the brain. This diagram (©absb, 2024), based on Puelles (2013), shows the primary domains.

SP = secondary prosencephalon, D = diencephalon proper, M = mesencephalon, R= rhombencephalon, and SC = spinal cord.

Two renowned anatomists, Rudolf Nieuwenhuys and Luis Puelles, published 2016 Towards a New Neuromorphology as a print version of their PowerPoint presentation (2013) at the Max Planck Institute (Leipzig). The main idea is that all vertebrate brains start with an identical topological (topos = place, logos = discourse) distribution of neurons along the horizontal and vertical axes (front-back and dorsal-ventral). During individual development (ontogeny), this blueprint is significantly deformed by neuronal migrations and all kinds of deformations of the neural tube (e.g., curvature, elongation, thickening, evagination, invagination, eversion, or surface enlargement). But the “bladder” never explodes. Through all the processes of distortion, the relationships remain intact. Eventually, the brain displays a new form characterized by a specific “topography.

See also: Evolution of Cortical Neurogenesis in Amniotes (Cárdenas, 2018).

This diagram shows the different domains within a neuromere (cross-section of an early vertebrate embryo). The red line shows the boundary between the sensory (alar) and motor (basal) domains. The neural tube's development follows a strict distribution of neurons within plates (radial) and neuromeres (longitudinal), which is part of the universal vertebral blueprint. (illustration based on Nieuwenhuis, 2016, adapted ©absb, 2024).

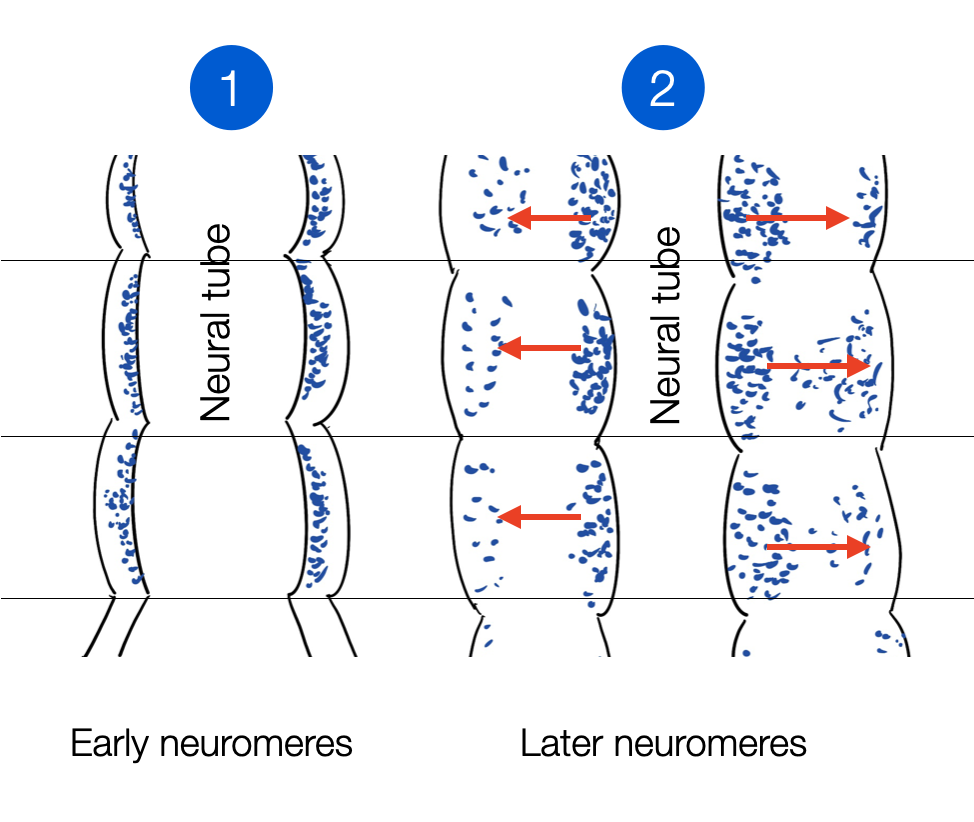

To explain the continuity through the profoundly transformative process (morphogenesis), Nieuwenhuys and Puelles describe “fundamental morphological units” (FMUs) as the universal building blocks of the brain. As they grow, they form segments like rings called neuromeres (neuro = nerve, meros = piece), i.e., the successive parts of the brain, with remarkable consistency across species. This has several concrete consequences for research. Researchers can use so-called “lower species” as valuable models, such as the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) to better understand our day-night rhythms or the zebrafish to discover the neuronal networks that initiate freezing vs. fleeing behaviors. The new anatomy has moved from classical anatomical exploration with a scalpel and microscope to genetic and molecular dissection.

The neuromeres develop radially, from the neural tube to the periphery, according to a genetic architecture that respects the original blueprint (adapted from Nieuwenhuys and Puelles, p. 66). They are like the bricks of the wall (©absb, 2024).

2.3.8

The Nature vs. Culture Debate

The PVT creates a two-class system — mammals vs. non-mammals — denying the latter social characteristics — and reduces the brain to the brain stem. It seems to ignore the work of a large group of researchers — see The Social Brain (Gazzaniga, 1985) — who have focused on the development of neocortical structures by Homo sapiens.

The nature versus culture debate is absent from the PVT. However, without tools, writing, and fire, any Homo sapiens with the same anatomy and genome as 300,000 years ago would be the same distance from a modern human as from a fish. Born into this contemporary culture, we believe love, tenderness, justice, smiling, and learning are natural. They are not.The PVT is based on two misconceptions about mammals. It reduces all mammals to a homogeneous group and applies a sweetened version of humans to the rest of mammals.

The PVT presents the evolutionary leap from “reptiles” to mammals as a radical, unhistorical step. It doesn't include the notion of time, of gradual evolution, as Darwin thought. Homeothermy (warm blood) appeared at about 260 mya, fur at 240 mya, lactation at 190 mya, and mammary glands at 180 mya. The PVT treats ALL mammals that have ever existed as a single group. However, most features attributed to mammals — such as homeothermy or myelinated vagal nerves — are not strictly exclusive to the three middle ear bones. Breathless diving and hypometabolic immobility are found in mammals. Sociability, crying for help, and parental behavior are not exclusively mammalian. The lines are not so clear.

Regarding HRV and mental health, the PVT focuses on modern humans. These studies do not represent the rest of mammals or even Homo sapiens. It ignores the difference between nature and culture. But the last 10,000 years represent only 3% of our presence as a species. We don't know if prehistoric humans smiled at each other. Cows and cats don't. The face is not the primary mammalian communication interface.

In conclusion, we can't observe humans as they have been shaped by technology and culture. Civilization has made us different— for better and for worse. The Anthropocene began with the first atomic bomb.

2.3.9

Primitive Brain and the “Savage”

It is a legacy of the colonial era to consider some people less human than “us.” This attitude is sadly reflected in the scientific descriptions of the past, which were mainly written by some “old white men.” It is interesting to observe how, in modern scientific literature, the terms old (as in “old vagal complex”) and primitive have been replaced by the more accurate formulation: conserved. Sometimes, words like “ancient” or “ancestral” are used, which are also respectful.

In popular culture (e.g., thrillers), the “reptilian brain” sometimes remains as the seat of our deep instincts. Too often, unethical actions are labeled as animal behavior. “He acted like an animal! A female concentration camp guard is called a “Buchenwald bitch." A mean woman is “a snake,” an informer is “a rat,” and an immoral man is “a pig."

While we might hope that 10,000 years of civilization (roughly the Holocene) would have educated us, we must face reality honestly. Let's do the math. The death toll from genocides and man-made famines between 1870 and 2020 ranges from about 36 million to > 85 million people. The death toll (civilian and military) from wars in the last 150 years (1870-2020) ranges from about 110 million to > 150 million people.

Witch hunts (1600-1900): The number of people accused of witchcraft and executed during this period is estimated at 40,000 to 60,000 deaths (mostly women), or even more. The massacre of Bucha (Ukraine) in 2022 shows us that brutal violence still exists. Can we blame some primitive part of us for this? Certainly not. Decisions to kill and rape are made at a high brain level in the cortex, if not by the soldiers, at least by the officers. Delusional belief systems, the causes of all wars, are cortical. No species takes conscious pleasure in torturing, humiliating, and starving fellow creatures.

In recent centuries, “civilized nations” have given themselves the right to loot and ruin other countries and continents to gain access to gold, tea, spices, oil, and cocaine. It is mankind's fate to inevitably develop the best and the worst in the same place. Alexander the Great spent most of his life making war. Napoleon revolutionized the French military, reorganized French education, and sponsored the Napoleonic Code — a model for later civil codes. But in those same 15 years, the Napoleonic Wars, caused by his urgent desire to dominate Europe, cost the lives of 1 million (French) and 2 million (European) soldiers.

2.3.10

The Omnipresent Polyvagal Anthropocentrism

“Man is not the measure to everything”.

A poem by Robinson Jeffer (1887-1962), (“The Humanist,” Collected 4:264)

In the first part of this website, we have seen how, after Darwin, the development of theories about the place of humans in creation split in two directions. Anthropocentrism is not a fallacy. It’s a bias, a distorted view, which eventually leads to fallacies. In the PVT, anthropocentrism is omnipresent.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, anthropocentrism views humans as separate from and superior to nature. It holds that human life has intrinsic value. At the same time, other beings (including animals, plants, mineral resources, etc.) are resources that can be legitimately exploited for the benefit of humanity.

Like other forms of contempt, anthropocentrism is subtle and often invisible. Most importantly, it uses an implicit logic. When Porges makes his case and mentions that reptiles are asocial in passing, the reader accepts it as a proven fact that doesn't need to be questioned. It goes without saying. It is self-evident. Have you ever seen crocodile mothers cuddling their babies? Of course not! Until you start to “Google and YouTube” them. You will find moving information (texts, images, videos): crocodile mothers carefully carrying eggs between their sharp teeth or turtles face to face, looking at each other (mother and child or couple). Indeed, a skin of thick scales — and short legs, fins, or wings — doesn't make hugging easy! But are we humans today really living up to the fantastic opportunity that Mother Earth has given us?

A distorted vision of creation — from the Scala Naturae to the Triune Brain (the ladder) — has paved the way for the anthropocentric polyvagal perspective. However, Porges' anthropocentrism is subtle, as he hides it behind a “mammals-first” paradigm. This dichotomous presentation constantly compares two groups: reptiles and mammals. This oversimplified view of the animal world (including humans) is problematic in many ways:

According to cladistic theory, there is no such group as “reptiles” unless we include birds, which the PVT doesn't do.

Taking “reptiles” to represent all non-mammals excludes fish, amphibians, and birds. Porges deliberately limits his argument by comparing some highly social mammalian species with reptiles, which are undoubtedly less social than fish and birds. The stereotypes of the solitary snake or the reptilian mother leaving her eggs unprotected are at hand, even though reptilian social life has long been described. In The Evolution of Parental Care (Clutton-Brock, 1991), parental care is not an exclusively mammalian behavior. See also (Doody, 2023).

Porges presents mammals as a unique, homogeneous group that exhibits parental care and social behaviors. This group is like a club to which members automatically belong if they have a myelinated ventral vagal branch originating in the nucleus ambiguus.

Linking brainstem evolution (dorsal-to-ventral migration of cardiac vagal neurons and myelinization of the ventral efferent vagus) to social behavior is problematic. Many species (e.g., toads and certain snakes) show migration or myelinization. «You must have both!” explains Porges in his Grossman commentary. « PVT proposes that only mammals have a myelinated cardioinhibitory vagal pathway originating from the ventral vagus. The foundational PVT papers have consistently stated that these two features, in combination and not independently, reliably distinguish mammalian RSA from respiratory interactions observed in other vertebrate species. ».

While Porges' argument makes sense, there are numerous caveats. The migration of cardiac vagal neurons CVN is often incomplete in many mammalian species, with some CVN remaining in the intermediate zone between the dorsal and ventral positions. Because the non-myelinated “dorsal” motor C-fibers have been identified primarily in small animals (cats and mice), researchers working with larger animals (e.g., sheep) have identified fibers with velocities comparable to B-fibers. This leads them to suspect the presence of myelinated dorsal motor fibers (Booth, 2021). Indeed, myelin and size are positively correlated — as we see with myelinated axons in an octopus (Boullerne, 2016), (Zalc, 2008). Porges, who rarely refrains from logical fallacies, accuses Taylor and Grossman of using a “straw man argument”: this is amusing. He is not wrong per se, but these skirmishes over “to be or not to be myelinated” are a smokescreen that hides more serious reservations about PVT. Obsessed with his social engagement argument, Porges doesn't see that the branchiomotor — or pharyngeal apparatus — was primarily developed and maintained for one crucial purpose: food! Secondarily, in terrestrial species, the laryngeal portion is related to respiration and vocalization, two highly interrelated functions.

Monophyletic

The hierarchical model of the Scala Naturae, as proposed by Aristotle and later adopted by the monotheistic religions, sees creation as a monophyletic ascent from the simple to the complex. Darwin, however, had a polyphyletic vision. Modern evolutionary biology, especially the cladistic perspective, has vindicated him, for evolution shows how multiple living things successively evolve (mutations) and select (natural selection) new traits to adapt to their ecological niches. These processes often occur parallel, as convergent evolution, in separate, unrelated clades. Wings in birds and bats or endothermy in birds and mammals are some examples. A strict unidirectional ladder model makes it difficult to understand how evolutionary acquisitions (e.g., myelination, sociality, language, diving reflex, fur, and migration from sea to land or back to sea) result in separate lineages (clades).

Anthropocentric traditional perspective

Ecocentric perspective

Utopia

From an anthropocentric perspective, the terrestrial niche-preferably temperate, around 70 °F (ca. 21 °C)-is the most desirable environment. Why evolve wings or fins when we have jets that slash through the sky and nuclear submarines that can stay underwater for months? But Homo sapiens, after 11,000 years of a spectacular Holocene, has pushed Mother Earth to the brink of a sixth massive extinction event. The Anthropocene, a still unofficial term, began around 1945. For the first time, humans demonstrated the destructive power of nuclear technology, which could soon destroy the planet — or make it uninhabitable for centuries. Such a possible event would repeat the catastrophe of the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 billion years ago. This time, humans would disappear, and perhaps water bears (tardigrades) would take over. We must invoke another pessimistic scenario — global warming — which is also a “man-made” process, but only slower. This bleak — though not unrealistic — vision should challenge the idyllic and naive Porgesian vision of humanity, which imagines citizens smiling at each other and “finding safety” in being together.

In Genesis, the male human — Adam — is presented as the crown of creation. Without challenging any religious tradition, the purpose of this website is to explore what modern science tells us about our species. Anthropocentrism tells us that we are unique in our ability to love, think, feel, and communicate. The PVT does this in a very particular way, praising all mammals for the qualities they are said to possess (such as parental care) and social life. It disqualifies non-mammals by attributing to their immobility and lack of sociality. The danger here is that we manipulate our knowledge of the surrounding creatures by believing that the diving reflex, tonic immobility, or social isolation are typical non-mammalian characteristics, which is wrong.

Crown of the Creation?

Mammalian utopia

Reptilian dystopia

The Veneer Theory

The veneer theory is a concept in evolutionary biology and anthropology that suggests human morality is a superficial layer (or “veneer”) that masks our fundamentally selfish and brutish nature. According to this theory, moral behavior is not innate to humans but a thin veneer developed to control and suppress our underlying, more primal instincts.

This theory is often referred to as Hobbesian because it echoes the views of Thomas Hobbes, a 17th-century philosopher. Hobbes famously argued in his work Leviathan that humans in their natural state are driven by self-interest and are in constant conflict, leading to a “war of all against all” (bellum omnium contra omnes). According to Hobbes, without the social contract and the imposition of laws and moral codes by society, human life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley also contributed to this perspective in Evolution and Ethics (1894). Huxley argued that the process of evolution, especially natural selection, does not favor morality or altruism but rather competition and survival. Therefore, ethical behavior is not a product of natural evolution but rather a cultural construct imposed to restrain our more basic, selfish instincts. This view is closely related to the veneer theory.

This resonates well with the prolific writings of Freud (the immoral unconscious), MacLean (the reptilian brain), and Porges (e.g., the monogamy switch).

Frans de Waal, a leading critic of the veneer theory, presents a compelling argument that morality is not a thin veneer over a fundamentally Hobbesian nature. His research on primates, especially chimpanzees and bonobos, suggests that the antecedents of human morality — such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation — are deeply rooted in our biology. So-called “humanity” is not a superficial or artificial layer but an evolved trait.

Moreover, as the chapter “Social & Communication” shows, social skills and parental behaviors are not limited to mammals but also occur in numerous other groups, such as fish, birds, and insects.

2.3.10

Further Reading

A History of Ideas in Evolutionary Neuroscience by Striedter in (Kaas, 2007).

Maturation of escape circuit function during the early adulthood of cockroaches Periplaneta americana (Libersat, 2005).

Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix (Smith, 2009). The appendix has appeared on several occasions. Is the appendix an advantage for humans?

The cecal appendix is correlated with greater maximal longevity in mammals (Collard, 2021). It has arisen at least 16 times in evolution.

From Mice to Mainframes: Experimental Models for Investigation of the Intracardiac Nervous System (Stoyek, 2021)

Intrinsic and extrinsic innervation of the heart in zebrafish (Stoyek, 2015). The zebrafish genome has recently been sequenced, and approximately 70% of human genes have at least one or more zebrafish orthologs (shared genes). The high degree of conservation of the zebrafish genome has made it possible to model the potential role of specific genes in many human diseases.

Zebrafish: a genetic model for vertebrate organogenesis and human Sleep-Active Neurons: Conserved Motors of Sleep (Bringmann, 2018).

Zebrafish a genetic model for vertebrate organogenesis and human disorders (Ackermann, 2003).

Origin of animal multicellularity: precursors, causes, consequences (Cavalier-Smith, 2017) is one of 17 articles on the theme: Evo-devo in the genomics era and the origins of morphological diversity.

Social interaction (Oram, 2022. During social interactions, male flies must identify potential mates (receptive female conspecifics) and fend off competition (conspecific males). Once a suitable female has been identified, males must respond to the female's cues in order to successfully copulate. Finally, males must balance their internal mating drive against the availability of mating partners, so they only court receptive females when their reproductive capacity is high. In Drosophila males, about 20 neurons have been identified that encode the arousal state of courtship.

Studying emotion in invertebrates: what has been done, what can be measured and what they can provide (Perry, 2017).

Environmental Ethics: Anthropocentrism and Non- anthropocentrism Revised in the Light of Critical Realism (Jakobsen, 2017).

From the scala naturae to the symbiogenetic and dynamic tree of life (Kutschera, 2011).

>> to the next chapter Sudden Death