3.2.0

Polyvagal Fallacies

When a researcher disagrees with a scientific hypothesis, one of the first things they do is look for logical fallacies or methodological flaws. This is a legitimate part of the scientific evaluation process. Critical evaluation of a paper's reasoning, assumptions, and conclusions is essential to scientific discourse. The term fallacy should not be understood as a moral judgment but rather as a logical error. Politicians, pastors, teachers, and lawyers use fallacies–for good or ill. Incidentally, fallacies are often called sophism, referring to the sophists of the ancient world– the founders of rhetoric. .

However, scientists must avoid sophistry, as it stands in the way of the truth. Moreover, being exposed by colleagues is a significant risk to reputation and credibility.

While a lawyer or a politician doesn't have to worry much about fallacies, a researcher avoids them at all costs. This chapter explores the world of fallacies and questions the logic behind the PVT. In our opinion, the PVT qualifies for many of the fallacies (or logic errors) we will describe. In the end, however, readers should decide for themselves.

In The Master List of Logical Fallacies, Williamson (2017) lists 146 fallacies. It can be difficult to distinguish one from the other. Fallacies are typically divided into two broad categories: formal and informal. We will focus here on informal fallacies, which we have grouped into five categories.

Fallacies are like playing cards with words and ideas – sometimes, building houses of cards.

Fallacies of Attention or Focus:

Shifting the argument to irrelevant details or misrepresenting the opposing position.

Grouping and Dividing: Errors in reasoning about groups and parts.

Cause and Effect:

Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc, and Cum Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc: Errors in inferring causation from correlation or consequence.

Non Sequitur: The statement doesn’t follow from the previous argument logically.

Circular Bias: The conclusion is used as the premise in circular reasoning.

Playing with the Words:

Ambiguous or misleading use of language.

Emotional:

Using emotion (pathos) rather than logic to persuade.

3.2.1

Fallacies of attention

False dilemma.

A cornerstone of PVT is what Porges calls the vagal paradox. In The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory (2017), he recounts the dilemma of a neonatologist who doesn't understand how vagal tone can be both positive and negative because newborns die from too much of it. This false dilemma narrows the focus to two possibilities and excludes any other possibility.

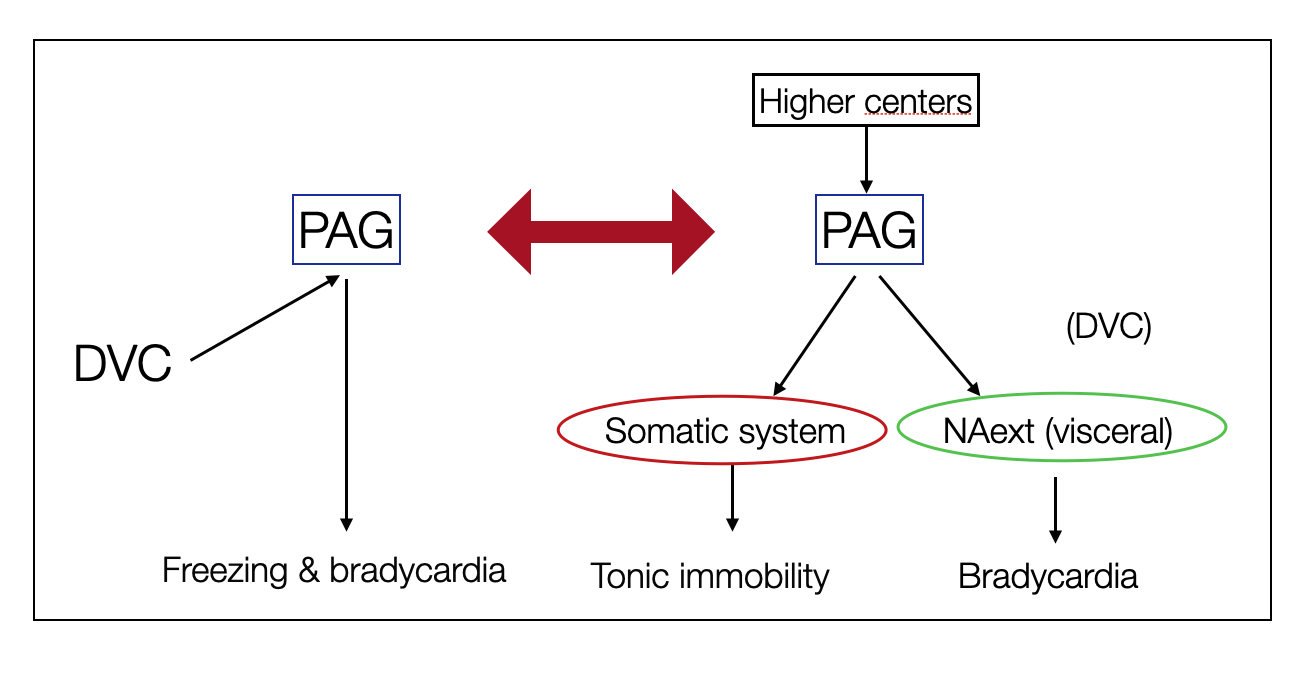

While we have seen that sudden death has many possible causes (e.g., genetics and environment), vagal heart slowing is virtually never the primary cause. Most cases in newborns and children are respiratory — not cardiac — arrests that are secondary to cardiac arrest. They very often imply genetic defects and a faulty environment (e.g., smoking parents). Moreover, new research based on optogenetics shows that the nucleus ambiguus (NAext) — not the DVMN — causes bradycardia (e.g., during the dive reflex).

False Dilemma

In Orienting in a defensive world: (1995), this paradox relates to the opposition between two types of down-regulation: RSA (phasic) and bradycardia (tonic). Here again, we see a false dichotomy. The PVT assumes that two different branches of the parasympathetic system are responsible for bradycardia (tonic) and HRV (phasic). But, as new research shows, the NAext creates the variability AND bradycardia, while the DMVN (dorsal) has more of a ventricular function, protecting the heart by hyperactivity of the Sympathetic or Heart stroke.

Attention deception (fallacy of attention) uses a mechanism similar to a street magician playing with cups and balls or an illusionist to divert and confuse attention. As Aristotle said about ethos, a rhetorical magician uses his words carefully to gain the trust of his audience. In the PVT, the complexity of the text quickly overwhelms readers, who focus on what they have already read or heard: “Reptiles are evil.” Understanding or challenging the PVT can take months or even years for a non-expert. There are so many topics! PVT has its paws all over the place.

Complexity is fascinating!

Porges likes to repeat that he was the first to be surprised by the positive response from a large non-academic audience. What he doesn't understand is the appeal of complexity. The use of sophisticated concepts leads to the fallacy of the argument from complexity. In his defense, we can see that some complexity is unavoidable because the PVT taps into highly scientific topics.

But, is it necessary to write something like “In a sense, psychophysiological parallelism implicitly assumed that the constructs employed in different domains were valid (e.g., subjective, observable, physiological) and focused on establishing correlations across domains that optimistically would lead to an objectively quantifiable physiological signature of the construct explored in the psychological domain.” (Porges, 2024)? Why not simply say: “Psychophysiological parallelism searches for measurable physical signs that correspond to psychological states?”

But the magic here is that Porges talks and writes about things that hardly anyone understands, including his peers, but at the same time uses a narrative that everyone understands: the snake, the good mother, or the lonely loser. He makes his audience feel that it's all very simple: a fallacy of oversimplification. The idea of a "big yo-yo" (dissolution-recapitulation) is tempting– it's hard not to like it!

3.2.2

Grouping and Dividing

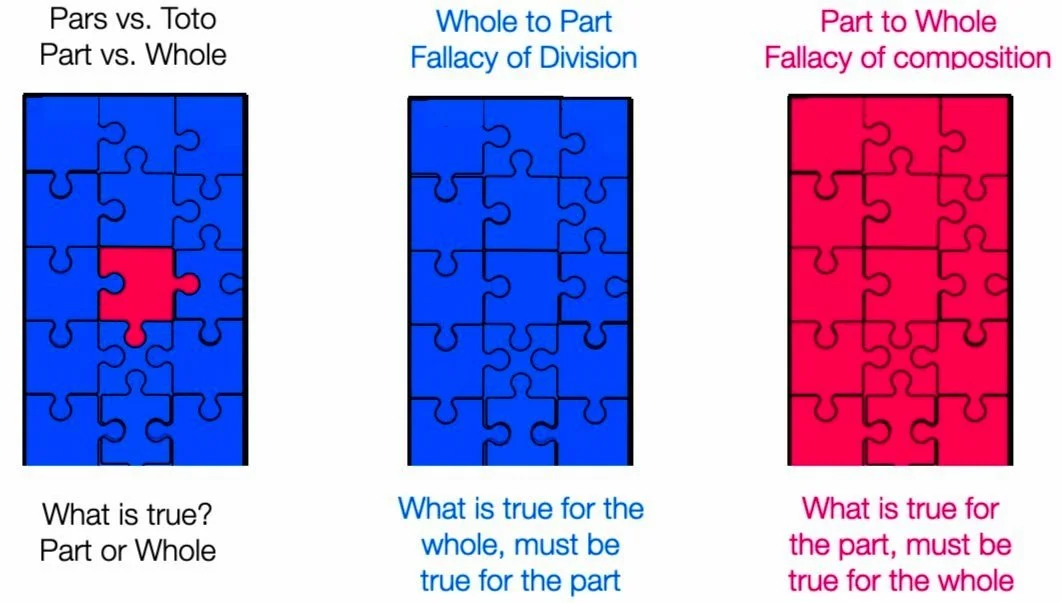

Composition plays with the relationships between parts and groups. An author can create groups (here the VVC) to serve his argument, exclude disturbing facts or select favorable elements (cherry picking), generalize, or misquote. This is also confirmation bias.

Hasty generalization occurs when someone makes a sweeping statement based on a small or insufficient sample size; Porges' conclusion that “reptiles are asocial” and “immobility is the default response of reptiles to a threat” seems to be based on only a few observations — probably knocking on the glass cage of a lizard in a pet store. The graph shows how an exception (a man with a “backpack”) becomes the rule.

Colligation is not a common fallacy, but it seems the most appropriate term to describe the linking (Latin: colligatio = connecting) of disparate elements. The overview presented in the last chapter shows how PVT "colligates" different temporal scales (e.g., phylogeny, ontogeny, psychology). Similarly, a sound engineer can lock a group of faders on his audio mixer and move them all together using only the master fader. Locking different faders or ladders (phylogeny, ontogeny, psychology, etc.) together creates an exciting narrative.

Compared to what?

One scale or many?

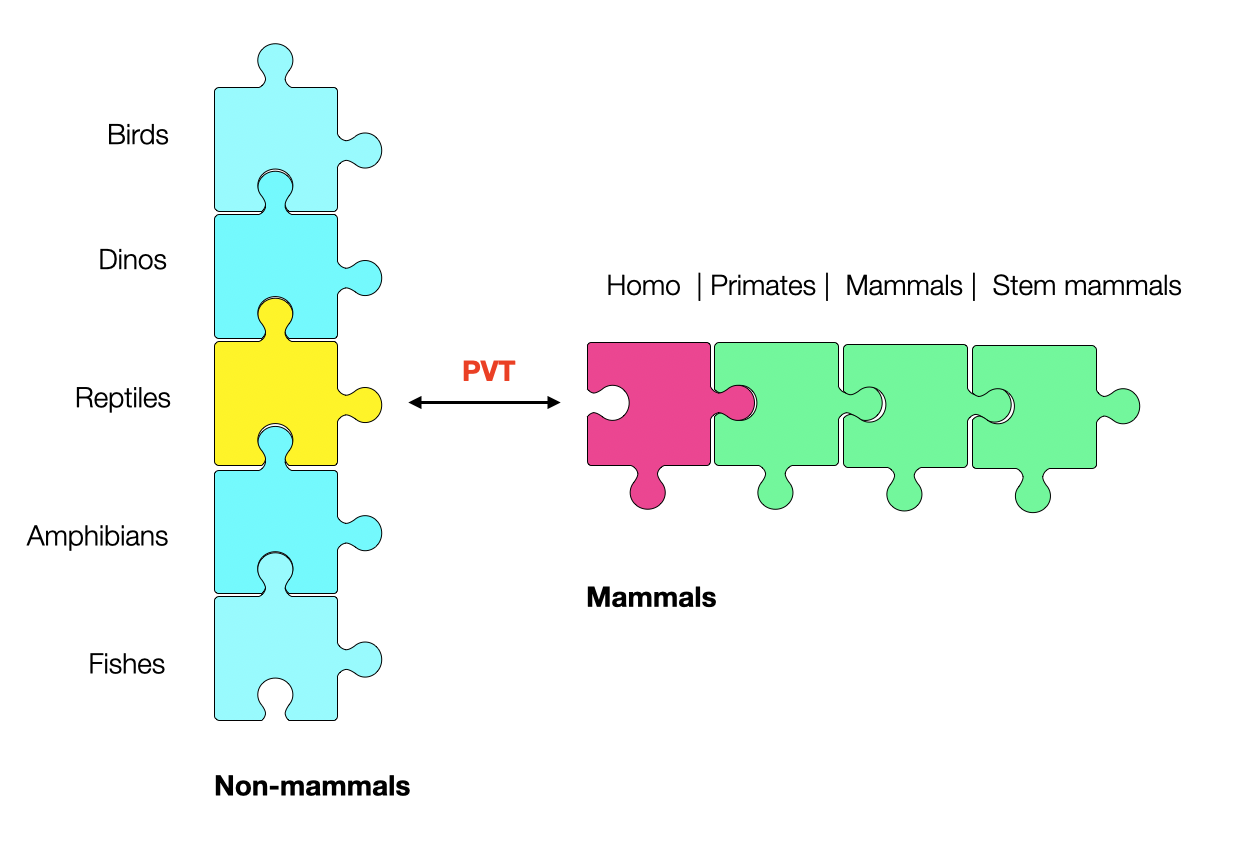

If we think of evolution scaled along a single medieval ladder (monophyletic genealogy), “reptiles” might represent the top level of non-mammals, and humans the top level of mammals. From this perspective, it is logical to compare these two groups. However, birds, dinosaurs, amphibians, and fish are omitted. If we take a cladistic (polyphyletic) perspective, which gives each group its path, we now compare humans with fish and birds–highly social animals. We may also compare the human brain stem with that of sharks, which share common characteristics. And why not compare mammals with some dinosaurs, which showed endothermy (like birds) and parental care?

The PVT focuses the debate on “reptiles” versus mammals. However, “reptiles” is an artificial paraphyletic group. In the polyvagal framework, “reptiles” remains not only for all sauropsids (birds, dinosaurs, and “reptiles”), but also for all non-mammalian vertebrates. (“fish”, amphibians). In addition, descriptions of mammalian behavior or anatomical patterns often refer to primates or modern humans. It doesn't include all synapsids (stem mammals and mammals). This is a double “pars pro toto” (part for the whole) fallacy or “fallacy of composition. Porges is caught in his ambiguity, believing he is comparing mammals to non-mammals, while instead comparing modern humans to crocodiles and snakes — cherry-picking?

Pars pro Toto

In a fallacy of division, the properties of the whole apply to the parts–if a car is heavy, then every part of the car must be heavy.

In a fallacy of composition, the properties of the part apply to the group–if an athlete is excellent, so is the entire team around him. If we observe some solitary reptiles in the desert, we might conclude that reptiles are solitary and asocial. These reptiles are non-mammals. Does this mean that all non-mammals are asocial, as the PVT implicitly suggests?

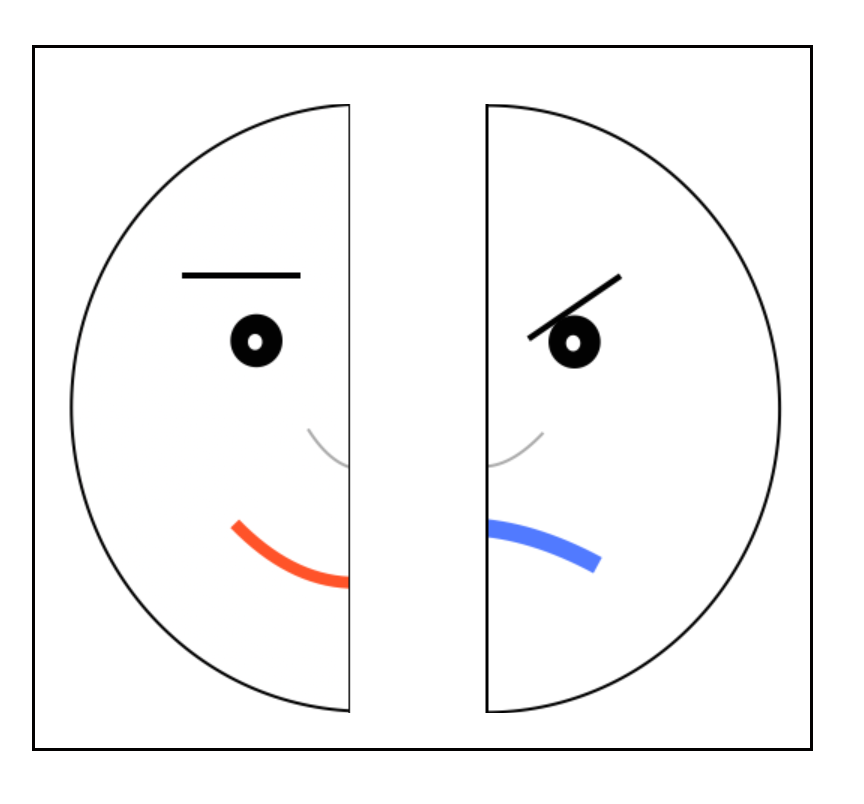

Two faces

According to the PVT, facial interactions help build a sense of security. But half of our facial expressions are positive, and half are negative. To assume that facial-to-heart communication (via the “smart vagal”) is reassuring by default isn't correct. It is a fallacy of composition.

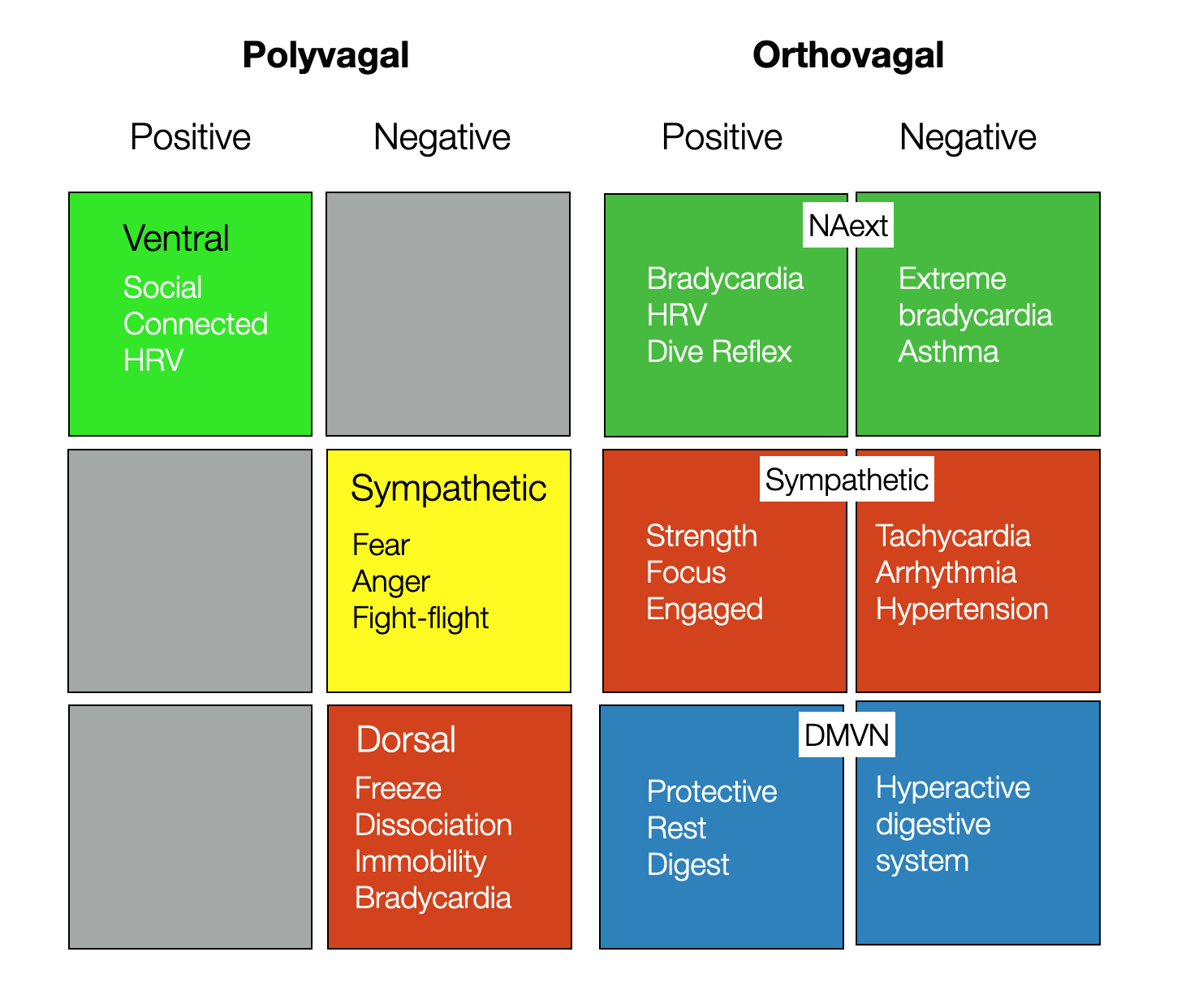

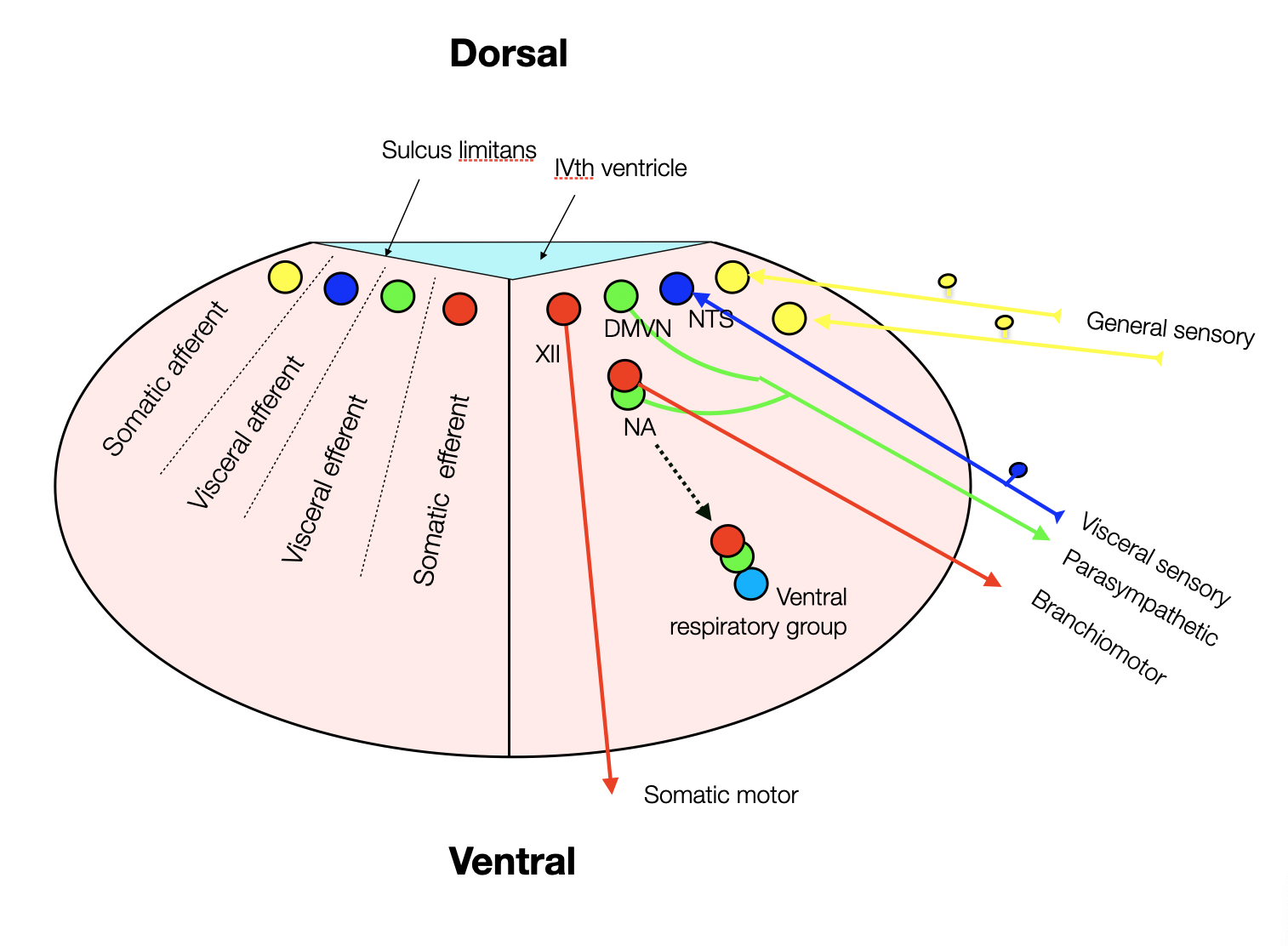

Another fallacy of composition: in the PVT, the ventral branch has only positive aspects, while the sympathetic system and the dorsal branch are mostly negative (with rare exceptions). From an orthovagal perspective, the parasympathetic branches have positive and negative aspects. So does the sympathetic system. To complete this, we should add the sensory vagal and the NTS. The DVMN has nothing to do with freezing, immobility, or dissociation, which are somatic behaviors and, for the latter, mainly cortical. Neuronal bradycardia is a product of the NAext (ventral).

More polyvagal fallacies of composition

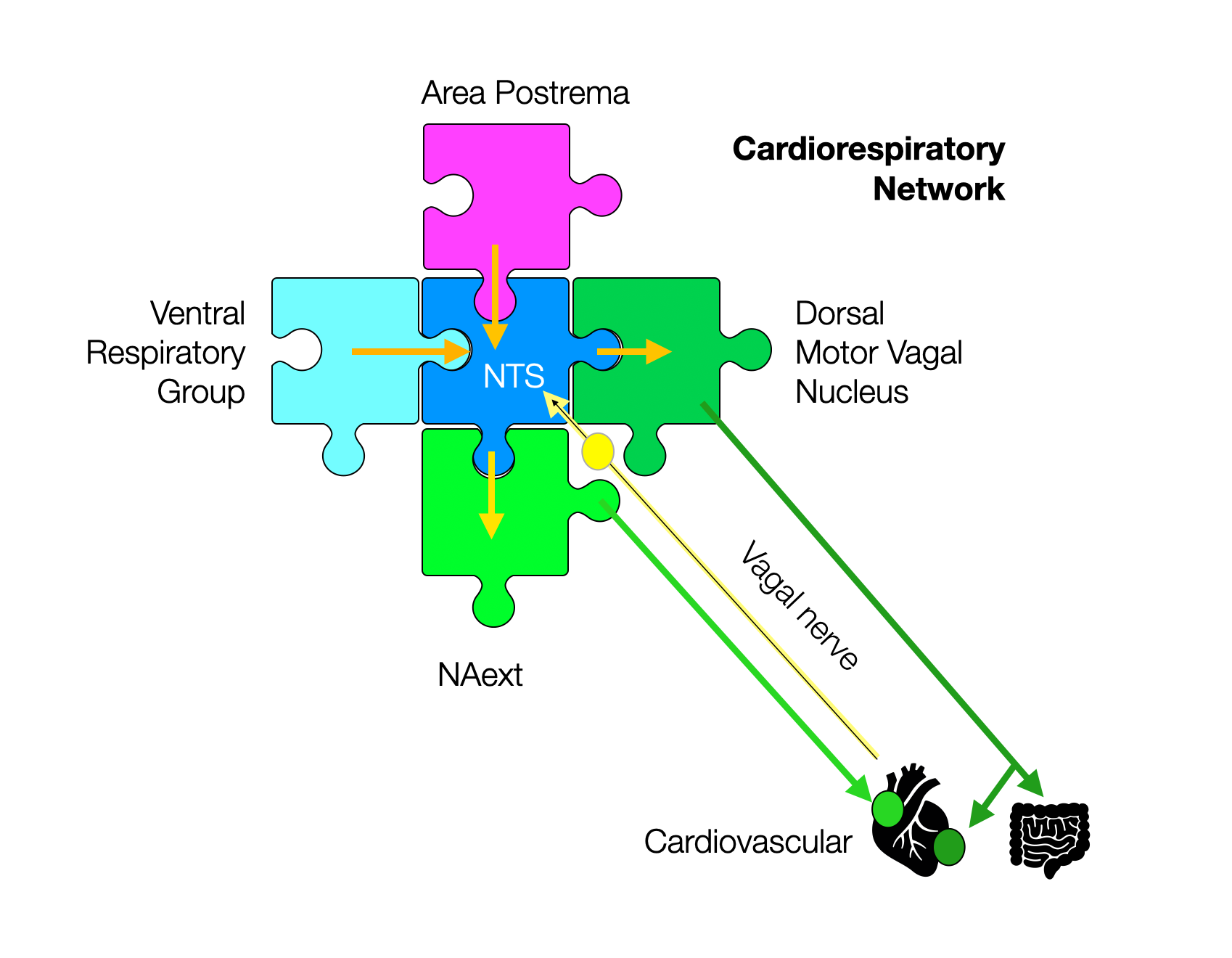

Does the fallacy of composition play a role in the polyvagal description of the brain stem? Let's put anatomical relationships aside for a moment and look at how the PVT has created antagonistic functional groups. To do this, we use a puzzle metaphor.

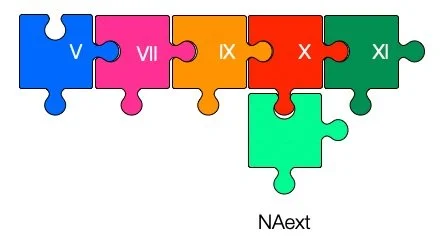

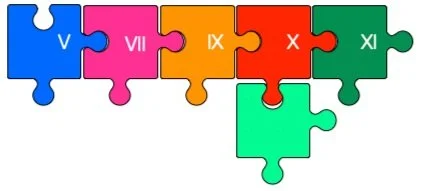

The PVT opposes two groups of cranial nerves.

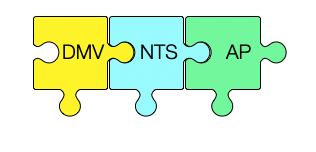

The Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC) or “Old Vagal” with the DMVN, the NTS, and the AP.

The Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC) or “Smart Vagal” with the five branchiomotor nerves and the external formation of the nucleus ambiguus (NAext).

The “New Vagal”

The “Old Vagal”

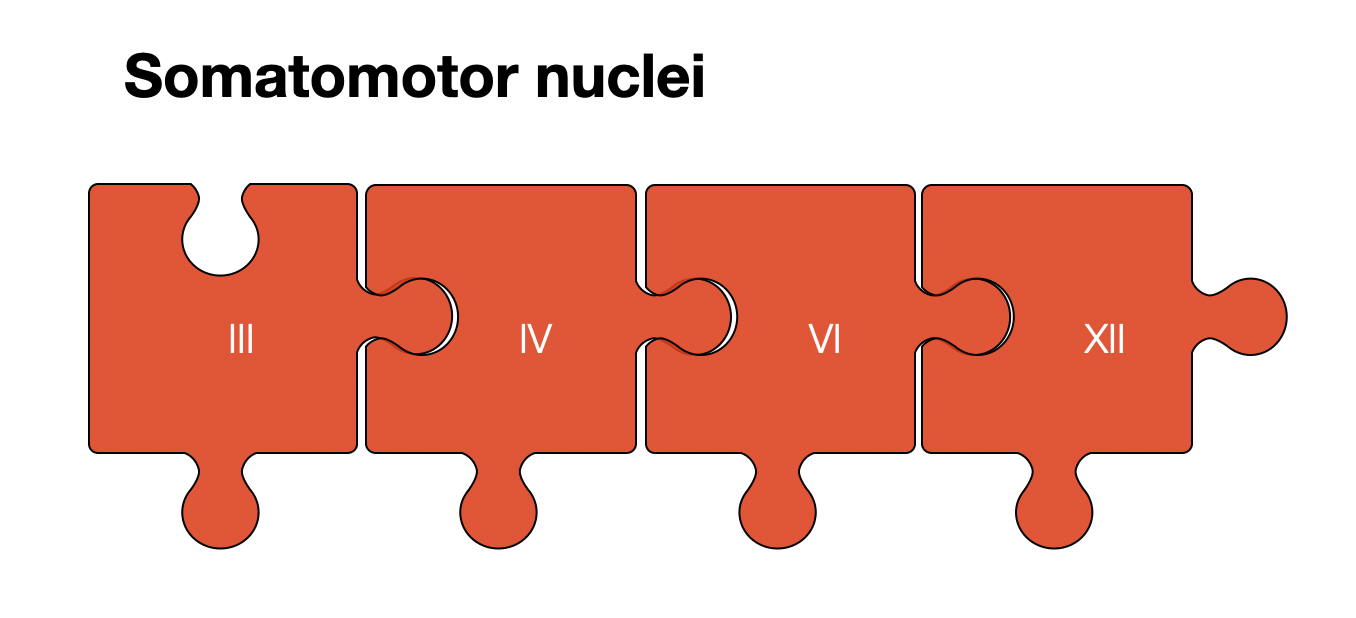

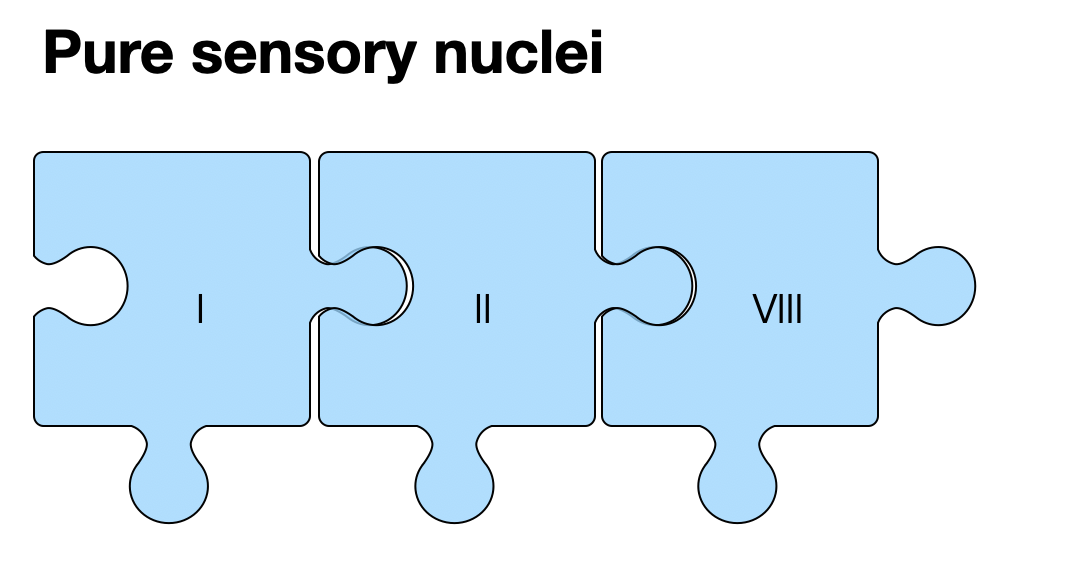

The PVT describes the ventral vagal complex (CN V, VII, IX, X, and XI) as the only neural support for communication. The somatomotor nuclei responsible for eye and tongue movements are not considered, nor are the cranial special sensory nerves (I, II, and VIII) responsible for olfaction, vision, balance, and hearing.

The Orthovagal model takes a different perspective.

All cranial nerves are involved in communication.

The NAext (ventral branch of the parasympathetic) is intensively connected to the NTS and functionally connected to the ventral respiratory group (via the NTS?).

Fallacies of association

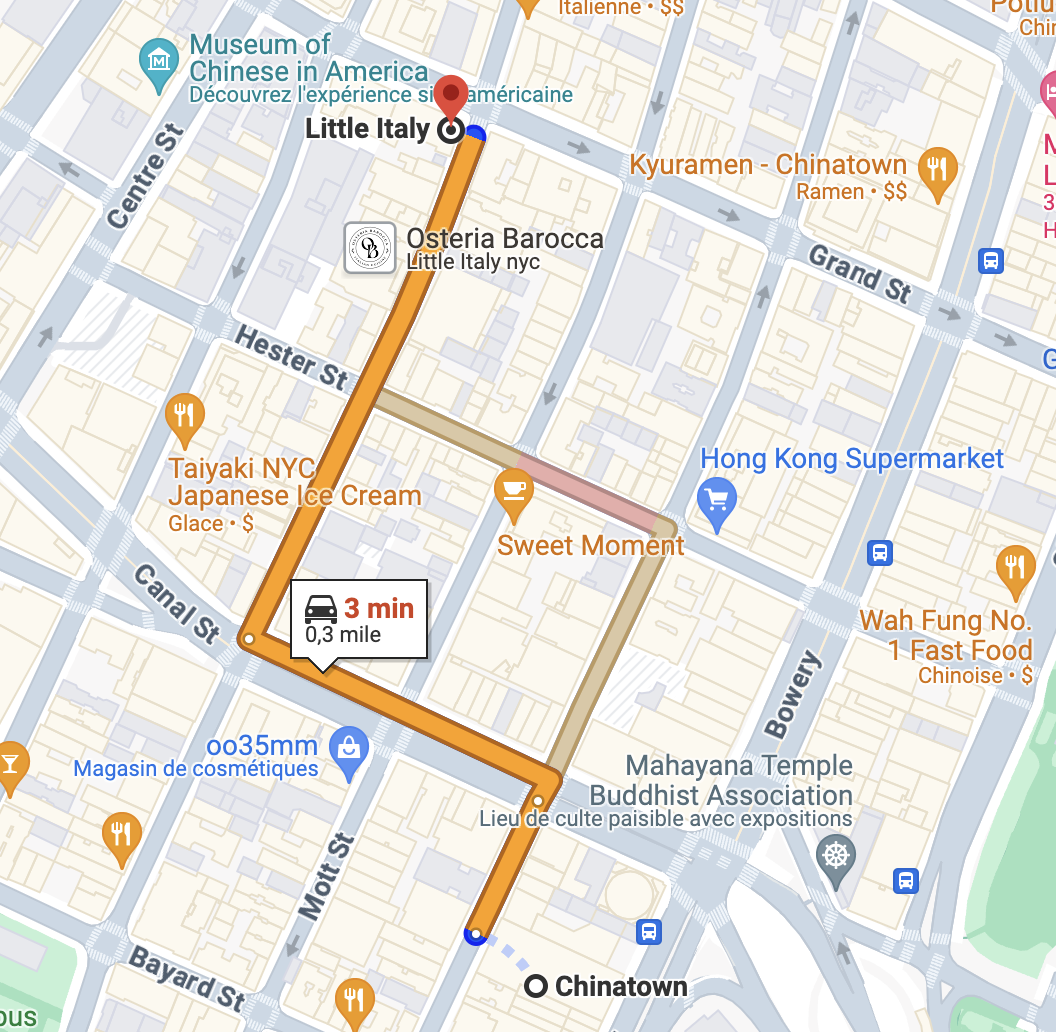

The discovery of the article by Bieger and Hopkins (1987) was undoubtedly the turning point in my quest, as I realized that the nucleus ambiguus wasn't a compact structure but a composite of at least four parts. The PVT commits several fallacies by assuming that the proximity of the dorsal and ventral parts of the NA predicts functional cooperation. To say that they communicate because they are neighbors is a form of association fallacy. It is as if we were to assume that the people of Chinatown and Little Italy in Manhattan must have a deep connection because of their geographic proximity. On the contrary, both populations certainly have interactions primarily related to their business and ethnic affiliations. Arriving within the same immigration period (especially 1880-1920) doesn't matter either. The assumption that being neighbors automatically entails communication can also be seen as a hasty generalization or ad populum fallacy. It erroneously concludes that physical proximity dictates similarity in actions or beliefs, ignoring individual differences.

In neuroscience, the anatomical proximity of two neural centers doesn't imply a functional connection. Neural pathways are complex, and communication between brain regions involves specific biochemical and electrical processes, not just proximity. In the first weeks of life, the human NTS (dorsal) and NAext (ventral) grow extensions toward each other and soon begin an intensive collaboration to regulate the heartbeat. No evidence exists for such extensive cooperation between NAext and the branchiomotor nuclei (cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, and XI).

Let's use some analogies (see below) to illustrate these lines!

Migration and Proximity

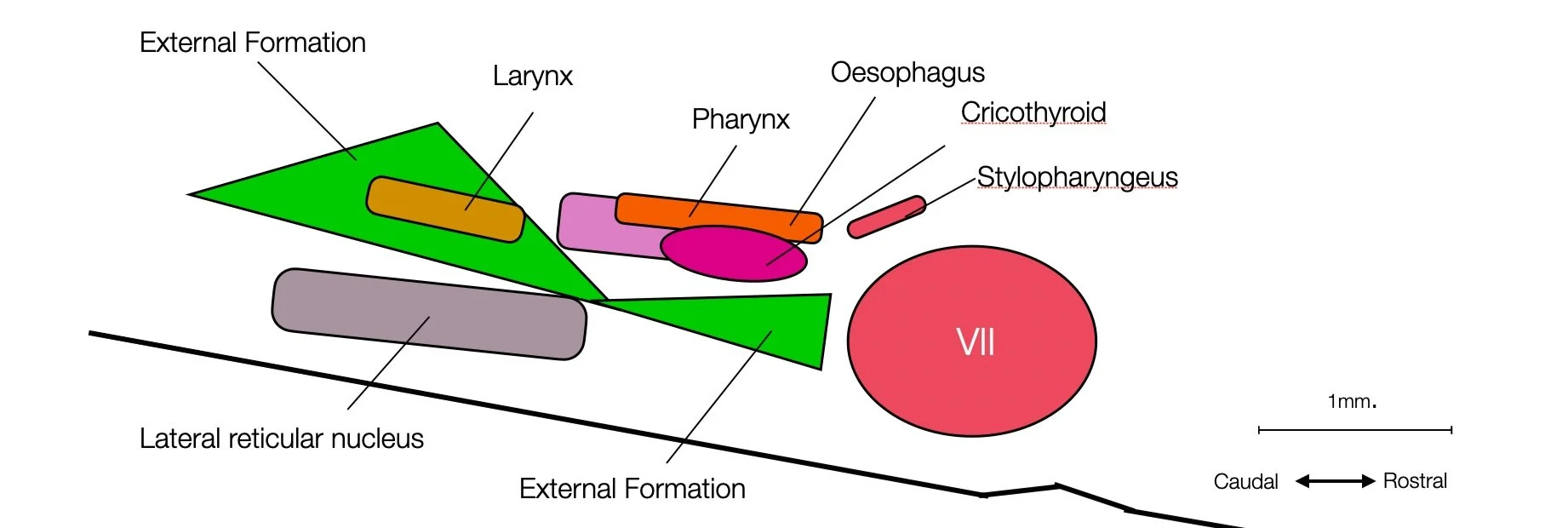

Anatomy is a geography on a different scale. Most neurons migrate radially (see graphic below) to the periphery as they first proliferate around the neural tube. This happens for the ventral and dorsal populations. Later, several populations migrate to a ventral position; this concerns not only the nucleus ambiguus (NA) but also the facial nerve, which shows an arcuate (curved) trajectory. However, anatomical proximity and similar timing don't imply physiological interaction.

Nucleus Ambiguus (NA) and External Formation (NAext) migrate in the same –ventrally. However, they retain specific functions before and after this migration. The NA relates to the pharynx and larynx; the NAext relates to the heart (bradycardia) and lungs.

Analogy: Here we compare neurons (anatomy) to human populations (geography and history). In the past, many populations from around the world migrated to Manhattan at the same time. Even though they lived in close proximity, each population retained a strong personal character. The Hong Kong Supermarket (see map) in Chinatown is unlikely to have a particular connection to “Little Italy” but instead to other Chinese American communities or even to Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Similarly, many populations of neurons share space in the brainstem without direct connection. They primarily coordinate at a higher level in the chain of command. Porges describes the branchiomotor neurons (CN V, VII, IX, X, and XI) as interconnected; we couldn’t find this connection at the medullar (brainstem) level. We didn’t find an evident connection between the two parts of the Nucleus ambiguus (NA and NAext).

The Embassy Quarter

This is another analogical comparison to illustrate the fallacy of proximity: Canberra, the capital of Australia, has the most extraordinary and compact cluster of embassies, often referred to as the “embassy quarter.” This Google map shows how the embassies are closely grouped. However, they don't share their secrets with their neighbors; they only share them with the foreign ministry of each country.

Proximity doesn't mean cooperation. The idea of a complex of branchiomotor neurons (CN V, VI, IX, X, and XI) based on proximity and phylogenetic commonalities (V, VI, IX, and X innervate branchiae in fish) is a proximity fallacy. We found some synchrony between the NTS (part of the “dorsal”) and the facial, related to respiration, but no local connections between branchiomotor neurons. On the other hand, the ventral part of the nucleus ambiguus (NAext) and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) develop a visible collaboration early in the development of the medulla.

Positioning the anatomical puzzle pieces

The PVT makes the NAext part of the Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC). The orthovagal model rearranges the elements, placing the NAext in contact with the NTS. Both structures share functional and anatomical connections very early in embryonic development. We don't find similar connections between the ventral (NAext) and dorsal part of the nucleus ambiguus (see Bieger, 1987).

Polyvagal vs. Orthovagal: In the first puzzle, the NAext (external formation) is positioned just below the group of branchiomotor nuclei that belong to this family of neurons. However, this grouping is in many ways arbitrary. The NAext is functionally connected to the NTS (dorsal complex) — the central visceral coordinator and the interface between the viscera and higher centers.

Here is a schematic representation of the Nucleus Ambiguus according to Bieger and Hopkins (1987). Many components are missing (e.g., respiratory, reticular and sympathetic centers). The dorsal area includes the compact, semi-compact and loose parts. The ventral area consists of the external formation (ventral parasympathetic) (©absb).

Fallacies of localization

In Le Médecin malgré lui, the famous French playwright Molière (1622-1673) depicts a group of doctors deliberating at the bedside of a sick patient. Each new symptom is interpreted as evidence of a single cause: “The lungs! The lungs, I tell you!” There is a danger in neuroscience of falling into the single-cause or localization fallacy, attributing a range of different behaviors or psychological functions to a limited anatomical group. Localization appears in Franz Gall (the bumps), MacLean (triune brain), Allan Schore (OPFC), and Porges (VVC vs. DVC). See (Lujan, 2019) on the “phrenological fallacy.”

3.2.3

Cause and Effect

The author inverts the cause and effect in this group, as if the river flows to the source. Time is inverted. Sometimes, synchronicity becomes causality (two simultaneous events are declared causal, one to the other). Finally, the hypothetical conclusion of an argument later becomes the accepted basis for the same opinion: a circular fallacy.

Although the PVT doesn't provide a clear description, it implicitly postulates a certain chain of causality: facial interaction > ventral parasympathetic activation > increased heart rate variability > sense of security > smile. In this loop, higher centers have little influence. Other non-facial causes (a bonus at work, a positive diagnosis from the doctor, or a nice comment on the Internet) are not considered. But won't these positive events trigger a “happy face” response?

In the PVT narrative, the “dorsal” causes a frozen response. It argues that some connection with the PAG (midbrain) is responsible. We see two errors here: first, the DVC is lower in the chain of command than the PAG, even though the NTS provides sensory information to the higher centers. Second, the PAG is highly connected to the Nucleus ambiguus (external formation). The bradycardia is caused by the NA and not by the efferent part of the DVC (DMVN).

Post hoc, ergo propter hoc

In this fallacy, the temporal sequence (B after A) is seen as a causal sequence. It's putting the horse after the car.

Cum hoc, ergo proper hoc (Correlation vs. Causation)

In this fallacy, which means “with it, therefore because of it,” the writer concludes that because two events occur together, one must cause the other. Below are two examples:

Depression and low HRV are often found together. It doesn’t necessarily mean that one causes the other. A third factor could be causing them, or their correlation could be coincidental. It's a mistake to infer causality from correlation alone. Proper scientific studies are needed to establish causality.

Most older people have reduced HRV. This does not mean they are more nervous or unhappy.

Young people with emotional dysregulation and conduct problems (Beauchaine, 2007) don't necessarily have reduced HRV (Beauchaine, 2019).

Ben is running with Suzy. They are both fast. Maybe "Coach Ben" is pushing Suzy. But could it be that "Coach Suzy" is pulling him forward? Or are they independent?

Circular fallacy

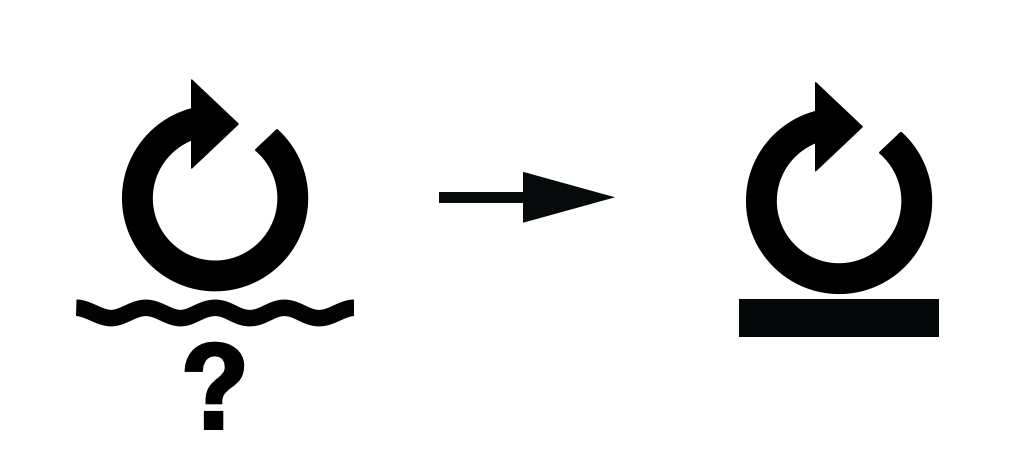

In this fallacy, the conclusion of the argument is used as a premise of the argument. The snake bites its tail.

In 1992 (Smart Vagal) and 1994 (Polyvagal Hierarchy), Porges laid the foundation for the Polyvagal Theory. As we have seen, the first argument (Sudden Death and the Polyvagal Paradox) is not convincing. However, over the next three decades, Porges built evidence from his hypotheses that he could apply to new fields (e.g., psychotraumatology, bird vocalizations, or autism) — appearing as an expert. Most of the premises about the PVT that appear in Orienting in a Mammalian World (1995) are presented as hypotheses. The word “propose” appears 17 times, “possible” 8 times, “possibility” 4 times, and “suggest” 9 times. He later presents these hypotheses as confirmed. Has he fallen into a Ponzi scheme where one hypothesis becomes evidence for the next hypothesis? What is the logic behind his repeated expression: “consistent with Polyvagal Theory?” From 1995 to 2005, Porges often cited articles written before 1994. Later, he rarely mentioned new scientific articles unless they confirmed the PVT. Is this the “confirmation bias” that all scientists know too well? He also cited himself extensively (hence our graphic of a self-serving snake), as if that were a sufficient basis. But what if the sources supporting his initial articles are outdated?

Through the circular fallacy, what Porges "proposes" in 1995 becomes a solid basis ten years later - the effect is then the new cause.

Confirmation Bias

After finding a dual vagal origin, which explains the duality of the parasympathetic system, Porges creates the term “polyvagal,” invents a social engagement system and a phylogenetic narrative–and never looks back. In this circular reinforcement, the first premise is never questioned. He keeps quoting himself or interpreting old sources to fit his theory. As a scientist, he should have considered all the articles and books on SID (sudden infant death) that challenge the vagal belief in sudden death, either in 1994 or later.

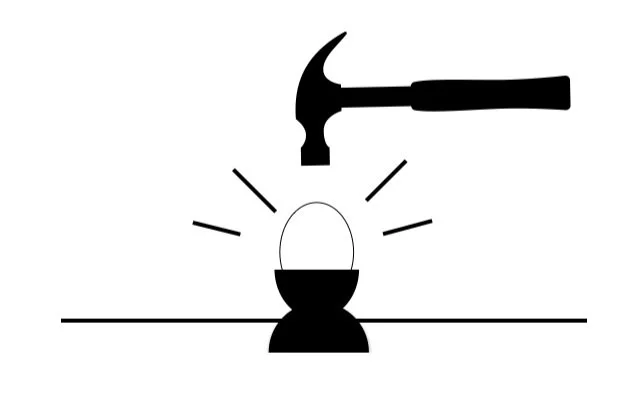

For Porges, the PVT must explain everything: autism, emotions, communication, psychotrauma, and much more. Isn't he like a handyman going around with his only tool — hammer — looking for problems to fix? That would be an instrumental fallacy.

If you only have a hammer, everything becomes a nail

3.2.4

Playing with the Words

As mentioned in the previous section on fallacies of attention, the PVT can confuse. This section looks more specifically at “playing with words.” It's in the nature of language to have words with multiple meanings. It also allows for omissions, repetitions, and other figures of speech that rhetoric uses to its advantage. For us researchers, all that remains is to patiently unravel the threads of the argument and meticulously clarify the terms. Only then will the inconsistencies of a theory begin to emerge one by one. The PVT undoubtedly benefits from a “charming” text that quickly subdues the reader. Many readings are necessary before one sees the possible rhetorical fallacies.

The juggler's art is to move the ball quickly to keep the audience's attention elsewhere. Similarly, a skilled rhetorician plays with words, moving swiftly through dense prose to gain authority over his audience.

Ambiguity

A recurring problem in the PVT debate is the “equivocation” of the concept of the nucleus ambiguus. For a good reason, this nucleus deserves the qualitative term “ambiguus,” which means “going two ways” (Latin: ambi = two sides and ago = going). This nucleus is like a Janus face: one side (dorsal) is branchiomotor, and the other side (dorsal) is visceromotor (parasympathetic).

Although Bieger and Hopkins provided a precise description of the Nucleus Ambiguus in 1987, many authors, including Porges, still discuss the NA's development, migration, and function without specifying which part they are talking about. This goes so far that Porges in Polyvagal Safety (2021, p.24) uses the term “preganglionic neurons” while talking about the motor nerves that target the striated muscles of the larynx and pharynx — a confusion with the parasympathetic nerve. Another ambiguity arises when Porges describes the maturation of the ventral vagal nerve during embryonic development. It's unclear whether he's talking about the maturation of the neuron (its total growth from soma to target) or the complete myelination — two different processes.

False attribution fallacy

False attribution is a misrepresentation of evidence (including stating something as a fact when it's not true or only partially true). It occurs when a speaker or writer, often without misleading intent, attributes a statement or belief to a source that did not make that statement.

This fallacy can take several forms, including:

Misquoting: Changing or taking the source's words out of context.

Fabrication: Making up a source or statement and attributing it to an actual or invented source.

Misattributing: Attributing a statement or belief to a source who did not make the statement or hold the belief.

Assuming that the "dorsal" is the cause of cardiac death, Porges concludes that Voodoo death results from diastolic dilation, proving the role of the dorsal vagal. However, when the heart stops — for example, after a respiratory arrest — the oxygen-deprived, exhausted heart muscle logically ends with relaxation. This isn't vagal; it's just mechanical. Porges (1997) thinks he has it covered, but — in our opinion — he plays with the sources. He quotes only those parts of Hofer (1975) that support his theories. However, Hofer did report that one-third of the test rodents responded to sudden immobilization with tachycardia instead of bradycardia. He is also much more cautious than Porges in his explanations of arrhythmias.

False attribution in scientific work can have serious consequences. It can mislead readers, making an argument appear more credible or authoritative than it actually is. This can lead to the spread of misinformation, undermining the integrity of the scientific process. Therefore, accurately attributing statements and beliefs to their proper sources is not just important, but essential.

False analogy

Jackson's dissolution and emotional regression

A “false analogy” or “faulty analogy” is when an argument compares two things based on common characteristics while ignoring significant differences. The idea is to demonstrate the logic of one situation by comparing it to another that is more easily understood by a large audience. However, the analogy falls apart if the two things being compared are too dissimilar. Often, a false analogy undermines the validity of an argument by oversimplifying or misrepresenting the situation's complexity.

In comparing the behavioral response (threat) to Jackson's dissolution, the PVT links two distinct domains: neuropathology (epilepsy or brain injury, inflammation, or tumor) and psychophysiology. These domains have significant differences in time scales. Neurological diseases generally develop over months, while physiological changes are on the scale of seconds or milliseconds. Moreover, as Striedter (in Kaas, 2007) reminds us, “Jackson tried to apply evolutionary ideas to clinical neurology, but his efforts failed."

Porges also believes that he is aligning his polyvagal perspective with the Triune Brain concept. However, they describe different anatomical areas. The MacLean description encompasses the entire brain, while the PVT describes the lower part of the brain stem, located in the “reptilian brain.

Don’t compare apples and oranges …

Truismus

Although not a true fallacy, many politicians and preachers use it to influence or manipulate their audience. It says nothing new, but reminds the listener of some old wisdom. If you add something like: “An old man told me” or “As my grandmother used to say,” the arguments are even more powerful. Truisms can help remind us of fundamental truths but can also be used manipulatively. The “yes” technique in NLP involves asking obvious questions to which the client is likely to say yes, making them more inclined to say yes–again– to more challenging questions.

The famous French playwright Molière (1622-1673) once wrote a famous dialogue in his play “Le Bourgeois gentilhomme” (The Middle-Class Gentleman), in which a newly wealthy man takes elocution lessons. He is astonished to learn that he has spoken “in prose” all his life; like most people, he does not talk in verse. Many readers of Porges may be similarly delighted to learn that they are practicing “neuroception,” a mammalian exclusive, without knowing it.

The polyvagal neologism “neuroception” (neuron νευρον = nerve, per-cipio = perceive) is indeed such a word, for it says nothing more than "perception through the nerves.” We have difficulty following Porges when he explains that neuroception explicitly designates the mammalian unconscious assessment of the environment in search of safety. Why should it be specifically mammalian? Because of the “intelligent vagus,” answers Porges. Do non-mammals not use their unconscious perception to assess their environment? If this perception is conscious, is it no longer “neuroception?” Do non-mammals not also constantly search for safety?

A truism says: “Drinking still the thirst,” “The rain is wet,” or “The moon is far away.” These statements are generally accepted as self-evident and uncontroversial. Truisms are often used in everyday conversation and various forms of writing. Still, they do not contribute unique insight or profound understanding unless presented as profound wisdom. For example, “Life is unpredictable” is a truism; it's a widely accepted statement that provides no specific insight or detailed observation. For “neuroception,” a neural system is mandatory. Bacteria, flowers, and trees are out! But starting with cnidarians, all animals have a neural system. Why does Porges reserve this term for mammals, the proud owners of social engagement?

Life is a story of threats and struggles for survival - an arms race, starting with single-celled forms. Constant perception of threats is the rule. The nervous system functions mainly without consciousness for economic reasons.

3.2.5

Appeal to Emotion

The appeal to emotion fallacy occurs when an argument is made by manipulating emotions rather than using valid reasoning or factual evidence. Examples include appealing to fear, pity, happiness, or a sense of justice to influence opinions or decisions rather than using logical reasoning or empirical evidence. It can also include using a particular tone of voice, images, or music.

Authority fallacy

As mentioned above, Porges has set himself up as the ultimate scientific authority for the entire community of polyvagal believers. We have seen from Pat Ogden how the cascade of quotes landed on Porges, who in Emotion: an evolutionary by-product of the neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system (1997) states without much ado that “although adaptive for the reptile, hypoxic triggering of this system may be lethal for mammals.” Porges never corrected this statement, although according to new knowledge, the mammalian diving reflex to hypoxia, a shared sympathetic and parasympathetic (ventral branch) phenomenon, is present in most mammals (Panneton, 2013, 2020), (Kjeld, 2021), (Veerakumar, 2022). In this study, Porges doesn't elaborate further, citing On the Phenomenon of Sudden Death in Animals and Man by Richter (1957): “Richter provided no physiological explanation except the speculation that the lethal vagal effect was related to a psychological state of “hopelessness.” In the last 25 years, though, “hopelessness” becoming “helplessness” has become an object of solid scientific research (e.g., Peterson, 1993; Greenwood, 2003; Maier, 2016; Fore, 2019; Bühler, 2021) implicating the mPFC, the medullar raphe, and the habenula.

I’m concerned that scientific authors have begun to cite Porges as a valuable source of information in anatomy, physiology, or evolutionary biology (e.g., Manzotti. 2024).

Too often, the one pointing out the sun casts the listeners into the shadows

Name-dropping

Excessive “name-dropping” or “quote-dropping” is another logical fallacy, mainly when it's used to persuade an audience based on the authority or popularity of the person being referenced rather than on the strength of the argument itself. This could be considered an “appeal to authority,” which argues that a claim must be true simply because a valid authority or expert on the subject has written or said it, without providing any other supporting evidence. This fallacy is often committed when the authority cited is not a specific expert (e.g., Porges is cited as an expert in biology or psychotraumatology).

In addition, if these names or quotes are misused or taken out of context, it could be considered a “quoting out of context” fallacy or a “misrepresentation of evidence” fallacy. Someone may omit parts of a statement to change or distort its intended meaning. While citing authoritative figures or quoting experts adds weight to an argument, it should not be the sole basis of the argument. The argument should also stand on its own merits and be supported by relevant, reliable evidence.

Let's look at an example of a chain of authority in polyvagal literature: Trauma and the Body. A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy (Ogden, 2006) was published in the Norton series with an editorial foreword by Daniel J. Siegel and a foreword by Bessel van Der Kolk. Ogden presents her work extensively here, supported by a considerable body of theory. The book is recommended by Allan Schore, Onno van Der Hart, and Christine Courtois. Pages 5-8 present the Triune Brain in detail (with a surprising quote from LeDoux, who despises MacLean). The polyvagal hierarchy is presented on pages 29-33. On page 97, Ogden supposedly quotes Bergman (2004:) “The increase in dorsal vagal tone has been observed in newborns who become hypoxic.” The article by Bergman (Bergman, 2004) does not contain the word “dorsal vagal”, but cites an article by Schore (2001), who cites Porges (1997) describing how the DVC can be lethal in mammals. Porges’s affirmation is based on On the Phenomenon of Sudden Death in Animals and Man (Richter, 1957). In this article, Richter concludes: “A phenomenon of sudden death has been described that occurs in man, rats, and many other animals apparently as a result of hopelessness; this seems to involve overactivity primarily of the parasympathetic system.” Three authors (Peterson, 1993), (Maier, 2016) and (Seligman, 2018) later repeated these experiences and similarly concluded that the rats died of hopelessness (or helplessness). It is a fact that rodents swim longer when they are given antidepressants. As Richter describes (p. 196), “After elimination of the hopelessness, the rats do not die.”

In summary, Ogden 2006 reports a theory based on observations she ultimately never read directly, made 60 years ago, that strongly suggest a different explanation.

Ad hominem and Ad Nauseam

Repeatedly disregarding polyvagal statements (e.g., “the asocial reptiles” or “the old dorsal”) is a variation of the ad hominem fallacy — in this case, toward animals or anatomical structures — even if unintentional. Politicians giving nicknames to their opponents are good examples of the ad hominem fallacy (e.g., “Sleepy Joe” or “Crooked Hillary”). See also Obama-Trump campaigns. Those statements are repeated “ad nauseam” (another fallacy) until fully implanted into the readers' brains.

Ad Hominem and Personification

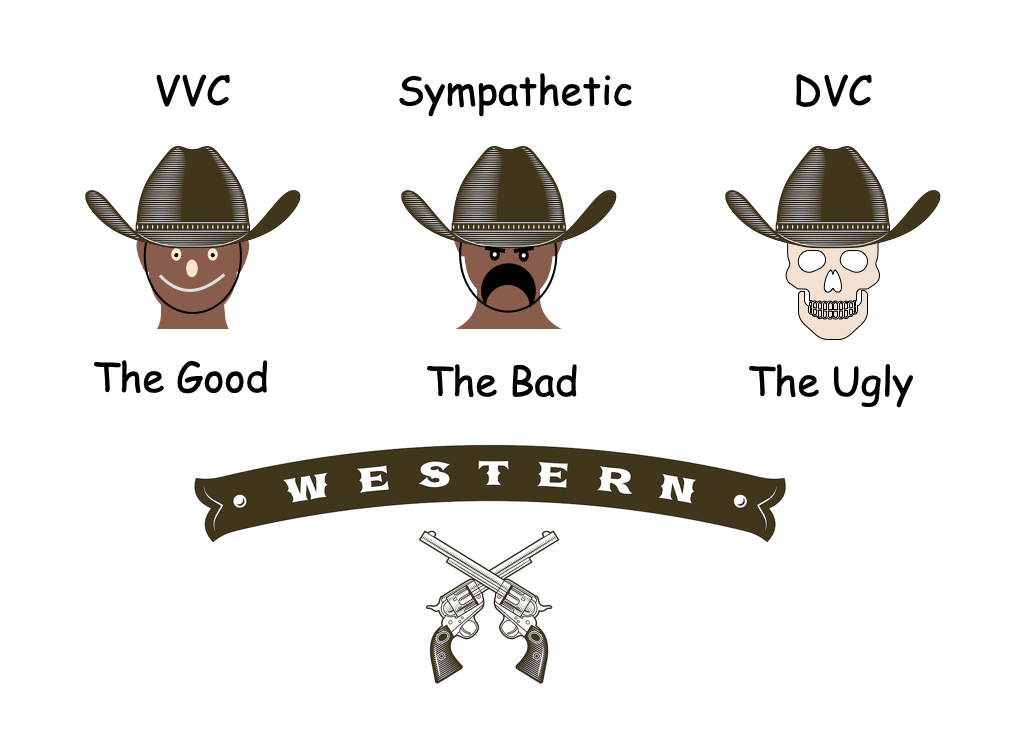

To promote the Polyvagal Theory, Porges and Dana literally create characters worthy of a classic western. The DVC (Dorsal Vagal Complex) becomes the "Old Dorsal" and the branchiomotor group becomes the "Smart Ventral". Dana, bypassing a scientific understanding of the brain stem, uses these clichés to role play.

Ad Basculum

When a person uses threats, it is a fallacy of power. These threats can be implicit or invisible and can come from an individual, a community, or even a society. In tyrannical situations, it can be dangerous to express independent thought. We have heard and experienced situations where public criticism of the PVT can result in negative consequences, ranging from disapproval and polite silence to outright threats.

Ad Populum (everybody knows)or Appeal to Popularity

According to the PVT, everyone needs love, contact, sex, intimacy, and a social life. While this may be true in an absolute sense, it is not so in real life: love often brings a lot of pain, social contact can be exhausting, and sex — not mandatory for a happy relationship — can be bliss or torture. Socializing with your angry boss isn't soothing. Reptiles are not necessarily solitary, and mammals are frequently lonely outside of mating.

This “appeal to popularity” or “ad populum” fallacy occurs when something is assumed to be true or good because it is popular or widely held. Unless the assumption is supported by significant psychological or sociological research, we have an ad populum fallacy. The problem typically occurs when general findings are applied universally without acknowledging individual differences and exceptions (e.g., reptiles). In today's ubiquitous social media, popular opinion can easily be mistaken for fact. People often prefer exciting stories to dry, reasonable facts.

Capitalization

Like a truism, “capitalization” is not a true fallacy. There is no false reasoning. It is, however, an easy way to influence readers. Depending on whether you write: “Planet Earth is burning” or “PLANET EARTH IS BURNING” makes a big difference. Of course, this typographical difference is taken as a metaphor: capitalization here means “making a mountain out of a molehill” or exaggerating the significance. It occurs when someone blows a small decision or difference out of proportion, treating it as if it were a matter of life and death or crucial importance, when in fact it is not.

The Latin word's origin is caput, capitis, meaning “head.” It has derivatives as the capital of a country (Paris for France), the Capitole, or a capital punishment (to be beheaded).

Does the term “capital” fit this biological context? We think that the PVT capitalizes on the different location of the NAext and the myelination of the ventral parasympathetic, as if this would give mammals a huge advantage. However, the exchange between the heart and the brainstem is faster in a lizard (with a short neck) than in a giraffe (with a 2-meter-long neck). In most mammals, the migration of cardiac vagal neurons (cVPN) to a ventral position is incomplete.

Appeal to Belief

The concept of an appeal to belief fallacy can be observed throughout the development of Polyvagal Theory (PVT). Although Porges probably did not intend to mislead his audience, the theory has evolved into something akin to an “appeal to faith,” where belief in the theory persists even in the absence of definitive evidence. In contrast to faith, science requires evidence.

Developing a theory based on circular reasoning involves logical fallacies such as “begging the question,” where the conclusion is assumed within the premises. This is similar to building a theory without a solid evidential foundation, similar to a “non sequitur,” where the conclusions do not logically follow from the premises. The demand for evidence may diminish for those deeply invested in the theory, leading to potential consequences that underscore the importance of avoiding such logical fallacies.

During this research, surrounded by enthusiastic PVT proponents, we were reminded of Hans Christian Andersen's tale of the Emperor's New Clothes. Such collective beliefs have always existed, only to be replaced by new ones. This idea is explored in the philosophy of science, especially by Thomas Kuhn, whose work on scientific revolutions and paradigm shifts provides a framework for understanding how paradigms can persist for centuries until a scientific revolution challenges and replaces them.

Does the PVT create a collective belief system?

In our opinion, the PVT has created an epistemological bubble in applied psychology and self-development. It isolates readers and practitioners from modern science and creates a vast corpus of questionable belief systems. Escaping this collective thinking is not easy. The psychological pressure within the group is intense, and most readers need more capacity for rigorous fact-checking. The lack of clear red flags makes breaking free even more problematic for those untrained in scientific thinking.

Fear of ostracism and a strong desire to belong are essential factors in maintaining adherence to PVT. The reluctance to admit error or appear foolish further perpetuates the belief.

Will PVT eventually collapse, as many collective constructs have in the past? We don't see it ending any time soon. Too many people have a vested interest in continuing to believe it.

Despite our belief that PVT is based on false assumptions and that its adherents are given a distorted scientific view of the brain, we are open to challenging these views. We encourage a respectful and inclusive dialogue.

Science and Faith

In an epistemological sense, faith and science are different approaches to knowledge and belief.

Science relies on empirical evidence and the scientific method to understand the natural world through observation, experimentation, and the formulation of testable theories and laws. The scientific method emphasizes repeatability, peer review, and the accumulation of evidence to support or refute hypotheses. Scientific knowledge is reliable because it is based on empirical evidence and logical reasoning. It is always subject to revision in light of new evidence or better arguments.

Faith is more subjective and personal, often based on trust in authority, tradition, or personal conviction. It doesn't change in response to new empirical evidence, as science does. Faith does not require proof or evidence in the material sense. It often exists in personal or community beliefs that are accepted without empirical validation. Faith can provide a sense of understanding, purpose, and meaning that transcends the material world and is not dependent on the scientific method.

Do we need Science?

While we acknowledge that science is not the only source of knowledge, it is essential to consider the following:

One can believe that the earth is flat and still travel comfortably across the continent. However, with such a belief, one can hardly plan a trip to the moon or a simple one-way trip around the globe. Similarly, things may go well if readers stay inside the Polyvagal Bubble with other Polyvagal followers. On the other hand, as soon as they move into a more rigorous scientific field (e.g., biology or physiology), it will be problematic. Your colleagues will shake their heads.

Many people question the validity of science, forgetting that it enables the use of advanced technologies such as the Internet, video channels, and smart phones for communication. They appreciate medical advances, sophisticated surgery, and painless dental work. In a word, science is valid and helpful.

The misuse of science to promote psychological services, often at the expense of accuracy, is disturbing. The growing self-help and human development business should not claim ownership of neuroscience, as it undermines the integrity of the field.

3.2.6

Porges, Grossman, and the Straw Man

A “straw man” argument is a logical fallacy in which someone misrepresents their opponent's argument to make it easier to attack or refute. Instead of addressing the actual points, they create a distorted version of the argument (the “straw man”) that's weaker or more extreme and then knock down that distorted version.

For example, if person A says, “I think we should have more regulations on industrial pollution,” and person B responds, “So you want to destroy all our industries and put people out of work?” Person B is setting up a “straw man” argument. Person A wasn't arguing for the destruction of industries; he was arguing for more regulations on pollution.

Straw man arguments are often used to avoid addressing certain parts of an argument and can distract from the issue at hand. It's considered a dishonest tactic because it involves misrepresenting the opponent's position.

In 2023, P. Grossman published Fundamental challenges and likely refutations of the five basic premises of the polyvagal theory (Grossman, 2023), repeating different points of his post, arguing that «The polyvagal hypotheses assume that RSA is a mammalian phenomenon, since Porges (2011) states “RSA has not been observed in reptiles.” I will here briefly document how each of these basic premises have been shown to be either untenable or highly implausible based on the available scientific literature. I will also argue that the polyvagal reliance upon RSA as equivalent to general vagal tone or even cardiac vagal tone is conceptually a category mistake (Ryle, 1949), confusing an approximate index (i.e., RSA) of a phenomenon (some general vagal process) with the phenomenon, itself.»

In response to the post and article by Grossman, Porges strongly criticized the expression« category mistake,» saying Grossman was ” using a straw man argument.» So, did Grossman use such an argument in his article?

Mammals have two specific new characteristics: the partial or complete migration of the cardiac parasympathetic neurons from a dorsal to a ventral position in the medulla AND the myelinization of the nerve. Porges is right about that, but Grossman addressed another issue of the PVT. He challenged the polyvagal postulate of “RSA, as equivalent to general vagal tone or even cardiac vagal tone.» This has been treated by Marmerstein (2021) in Direct measurement of vagal tone in rats does not show correlation to HRV. Therefore, I disagree with Porges' epistemological correction.

3.2.7

Inconsistencies & Cognitive Dissonance

The Polyvagal Theory (PVT), although presented as a scientific framework, contains significant inconsistencies that call into question its status as a robust theory according to the principles of scientific methodology. While the intention to emphasize the importance of the body in neuroscience is laudable, PVT's approach seems more populist than rigorous, particularly in its opposition to the so-called “cortico-centric” perspective. Science is not a battleground for political allegiances; facts govern it. The selective use of facts to support a populist narrative undermines the integrity of any scientific theory.

Here are some of the most apparent logical flaws and inconsistencies within the theory:

Inconsistent role of respiratory centers: In his recent work, Porges emphasizes the importance of breathing as a regulator of emotional states. However, the PVT largely ignores the role of respiratory centers in initiating heart rate variability (HRV).

Inconsistent use of the Triune Brain Model: Porges celebrates the triune brain model, which places the reptilian brain as the most primitive, rigid, and instinctual part of the brain. MacLean locates the source of emotions in the limbic system in the front brain. Porges, on the other hand, asserts the unique role of the brainstem in regulating emotions. Yet the brainstem, according to MacLean, is part of the reptilian brain. Isn’t it confusing?

Narrow definition of “body”: While PVT aims to restore the importance of the body in emotional regulation, it focuses almost exclusively on the visceral organs, neglecting the essential role of the somatic body-skeletal muscles, proprioceptors, and skin receptors in these processes.

Unsubstantiated claims about the ventral vagal complex: Porges introduces the concept of the “ventral vagal complex” as an interconnected system that governs emotional regulation. However, no empirical evidence supports such an interconnected network among the cranial nerve motor centers (V, VII, IX, X, XI). These centers take orders from higher cortical regions, coordinating muscle actions (e.g., PAG and frontal cortex)–they don’t operate as an autonomous emotional control system.

Misinterpretation of phylogeny: Porges repeatedly refers to “our reptilian ancestors,” a notion at odds with modern cladistic phylogeny. This outdated understanding of evolutionary biology calls into question the basic assumptions of the PVT.

Lack of a coherent theory of emotion: The PVT posits that a group of cranial nerve centers (V, VII, IX, X, XI) influence the vagus nerve to increase heart rate variability (HRV), which supposedly induces a state of safety. However, this model does not explain how these brainstem circuits alone can produce positive emotional states without the necessary involvement of higher brain centers. Emotional states such as joy, safety, and social bonding are perceptual and cognitive processes that require more than autonomic feedback.

Questionable “neuroception” mechanism: The concept of “neuroception” in PVT is rooted in the idea that the “smart vagus” (located in the most primitive part of the brain) is responsible for detecting safety cues. However, this structure is primarily motor, not sensory, so it is unclear how it could perceive safety cues or regulate emotional responses without input from higher cortical regions that process sensory information.

Incomplete representation of sensory feedback: While Porges emphasizes the role of visceral feedback, he neglects the somatic and sensory inputs-such as olfactory, visual, auditory, vestibular, and gustatory cues-that are critical to emotional perception and regulation. Furthermore, feedback from the visceral organs, mediated by the vagus nerve, converges in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), part of the “dorsal vagal complex,” which Porges himself links to extremely adverse outcomes such as depression and dissociation. This contradictory view of the same structure as both beneficial and harmful is problematic.

Co-opting

During her 2024 campaign, Vice President Kamala Harris was accused of co-opting because she declared: “I have a gun at home (...) if someone breaks in, I will shoot.” (New York Times, 2024 October 7). Intentionally or not, she was borrowing Republican rhetoric. The Democrats still want to ban guns. We have criticized the PVT for insufficiently reflecting new scientific evidence. However, Porges may have found a subtle way to adapt his theory to the present without sacrificing the core theory (hierarchy, neuroception, co-regulation) by using ad hoc fallacies. Another way is to borrow rhetoric (e.g., psychotraumatology.) Finally, he cites articles by authors such as Gourine and Machhada that fundamentally challenge the PVT–neglecting new research (Gourine, 2019, Macchada 2020) showing that optogenetic DVMN stimulation increases the left ventricle ejection fraction by 26%.

In some cases, co-opting can be seen as cultural or intellectual appropriation — for example, when one author adds elements from other authors. Does Porges do this by incorporating attachment theory, Jacksonian dissolution, Darwin's writings, and more) to serve his theory?

Ad Hoc Fallacy and Special Pleading

I have long been discouraged by the fact that as soon as I thought have found a flaw or a contradiction in the polyvagal construction, I quickly found a statement by Porges making an exception.

In The Significance of Stillness, in Polyvagal Safety (Porges, 2021. p.232), Porges explains: «Most people conceptualize the sympathetic nervous system as a fight-and-flight system. However, (…) it has other more prosocial functions and supports energetic activities. Without a well-functioning sympathetic nervous system, we would be lethargic. Our exuberance and upbeat movements and feelings depend on the sympathetic nervous system as an energy source.

In Love’s Brain: A Conversation with Stephen Porges (Loizzo, 2018), Porges says: “In my own model, the older evolutionary part of the vagus —with is circuits in the back-facing dorsal side of the brainstem—is a very powerful system of calming that enables the deepest forms of connectedness and intimacy.”

Concerning the theories of emotions: “There are both top-down and bottom-up signals that regulate our physiology” (Porges, 2021, p. 179).

Gestures (Polyvagal Safety, p. 177) participate in the communication.

But didn't Porges spend the last 30 years equating sympathetic responses with a phylogenetic regression, the dorsal vagal with a potentially lethal one, promoting a bottom-up theory of emotions, restricting the Social Engagement to face and voice? We see a pattern here. Porges tries to cover all the angles. Going back to the study of fallacies, we found a logical fallacy called ad hoc reasoning. This fallacy occurs when someone continually adds new, often arbitrary, justifications or exceptions to a theory to explain away any evidence that contradicts it, rather than revising or discarding the theory itself. In this case, the person is trying to “patch” the theory to protect it from falsification, making it more convoluted and less credible.

We must distinguish opinions from scientific statements. The fallacy here can be categorized under informal fallacies, specifically within the broader category of fallacies of inconsistency. Here are two possible classifications:

Ad hoc fallacy: As mentioned earlier, this is when exceptions or modifications are introduced to save a theory from counterexamples or contradictions. It shows an inconsistency in reasoning, where the theory is repeatedly adjusted to avoid disproven instead of being revised or rejected.

Special pleading: This is another closely related fallacy, where someone applies standards, principles, or rules to others but exempts themselves or their theory without a valid justification. Adding exceptions to preserve a theory without a clear, logical explanation could be considered a form of special pleading.

The two fallacies fit best under the fallacies of inconsistency due to the contradictory and arbitrary nature of adding exceptions, which undermines the theory’s coherence.

Of course, we expect Porges to claim that we, like Grossman, are setting up a strawman fallacy. This is indeed debatable. We may have missed some pages of his books or articles and misquoted him. But we must maintain our rejection until he integrates the exceptions and reformulates his theory.

In summary, we consider the polyvagal theory to be characterized by significant cognitive dissonance, logical gaps, and selective use of evidence. By cherry-picking facts to fit its narrative and ignoring well-established physiological and neurological principles, the theory struggles to present a coherent and scientifically credible model of emotional regulation. Rather than advancing our understanding of neurobiology, PVT risks distorting the complexity of human emotional processes with oversimplified and sometimes misleading claims.

>> to the next chapter Polyvagal Informed