4.1.0

Polyvagal Informed

Are you “Polyvagal-informed?”

This chapter briefly examines the various practical applications of the polyvagal theory. As many therapists have become interested in PVT, they have reframed their work: new clothes, same body. Porges has forged the expression “polyvagal-informed” or “informed.” Once again, recalling the “neuroception” truism, he creates an elite group of followers who are “in the know.” As a result, a new trend of treatments based on PVT has emerged. Whereas yesterday, laypeople could become hypnotherapists or NLP coaches in a matter of weeks, today it is possible to become polyvagal overnight and, more importantly, to advertise oneself as such.

In The Dark Side of Polyvagal Theory Brian Dunning (2022) criticizes the phenomenon of polyvagal coaches, comparing the short polyvagal training with the extensive training of a certified coach.

Why do yoga teachers suddenly give sophisticated explanations about a healing practice that has been around for centuries? Why do body workers play polyvagal coaches and engage in questionable psychological interpretations? Does the convergence and pressure of the marketplace require such forms of self-promotion? For a historian, it's reminiscent of the heyday of psychoanalytic practices in the 1960s, when “wild psychotherapy” was practiced. A cook or a secretary with enough ambition could open a practice without worrying.

I read every chapter of those polyvagal books and couldn't find an exercise we didn't know. We were confused and doubted our judgment: What is new?

Read: What is a Polyvagal Therapist, and How Can They Help You?

Reminder

To be clear, most of the vagal exercises recommended by various authors and experts — such as breathing, humming, and gargling — are, in my opinion, beneficial and generally safe, although we make no guarantees. I don't doubt the results. But that's not the core issue. My concern is with the Polyvagal Theory (PVT): while the polyvagal pep-talk surrounding it may help with promotion, the theory remains so problematic that it should, at some point, worry practitioners and clients.

Does your yoga session have to be “polyvagal”?

4.1.1

Polyvagal Informed Neuromarketing

Does it help your business to call it “Polyvagal -informed”?

In discussing the differences between specific auditory training (e.g., Tomatis, Bérard, or the Listening Project), Porges offers a candid observation (Porges, 2014). He states: “Although LPP is a 'sound therapy,' it is not a traditional clinically available AIT (e.g., Berard, Tomatis) and differs from these procedures in method and theory. First, LP is based on polyvagal theory and reflects a strategic attempt to address the neural regulation of specific structures involved in the social engagement system.”

At the risk of sounding polemical, this statement seems more like a sales pitch than a scientific one — it is neuromarketing. How the therapist presents his treatment plays a significant role in creating a powerful placebo effect. And it sells!

On the NIBCAM website, we read how Ruth Buczynski, PhD, has been combining her commitment to mind-body medicine with a savvy business model since 1989. The business is good. The buzzwords are: “polyvagal, shame, compassion, trauma, or abandonment.” ISC also brings in “attachment, shame, anger, or self-compassion." Why not?

Is this new old jargon just a way to follow the hype, or does it add real value?

I regularly encounter colleagues who argue passionately for the importance of attachment as if it were a brand-new discovery. Yet, Bowlby (in the '50s) and Ainsworth (in the late '60s) had been publishing on the subject for a long time.

Adopting the PVT can have significant economic benefits in the coaching and therapy market. Adopting and promoting a “polyvagal informed” approach transforms anyone who has taken the training (e.g., NIBCAM) into an “informed expert” who is in the KNOW! This comprehensive neurobiological, phylogenetic, ontogenetic, trauma-informed and compassionate approach provides certainty and recognition in an uncertain field. Is it a revival of the golden era of psychoanalysis when in the French 60's Jacques Lacan claimed the strange meme: “Le psychanalyste ne s'autorise que de lui-même” (the psychoanalyst authorizes himself only from himself)-meaning that anyone could claim the title of psychoanalyst and charge therapist rates?

Understanding the “polyvagal yo-yo” doesn’t take hours. It’s so logical and catchy that no anatomy or biology knowledge is needed.

4.1.2

Can We “Heal the Vagus Nerve?”

We are told to train, stimulate, or heal the vagus nerve. This is often touted as a new piece of wisdom that can work miracles — books and videos on the subject abound.

My exploration of bookstores in various countries and languages has revealed various publications, generally offering two different perspectives:

The authors propose vagus nerve training but notably omit the Polyvagal Theory. For example, Activate Your Vagus Nerve (Habib, 2019) conspicuously omits the parasympathetic portion of the nucleus ambiguus (NAext), which modulates the heartbeat.

The authors spend the first half of their book on polyvagal theory, typically with a touch of generalization and fantasy. Their writing is engaging, but they remain silent on the vagus nerve's role in digestion, immune responses, heart protection, appetite regulation, or metabolism — not a mention! The dorsal is consistently portrayed as responsible for metabolic shutdown, depression, and dissociation–which is unscientific.

Despite their differences, both groups unanimously advocate breathing exercises, good sleep, healthy eating, and anti-stress techniques: nothing specific. They present these age-old practices with scientific or pseudo-scientific explanations in a new light, effectively repackaging the same medicine in a new bottle.

4.1.3

Polyvagal Informed Osteopaths

For some reason, osteopaths have made PVT a big deal. Since they treat soft structures and not just bones like a classical chiropractor, they can logically deal with compressed nerves like the vagal nerve — why not? The inconvenient part is that, based on a modest knowledge of such a complex subject, they write exciting books about the PVT that find an enthusiastic audience.

Stanley Rosenberg

In Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve (2017), Stanley Rosenberg, “an American-born body therapist living in Denmark,” offers interventions for body workers and self-help exercises for laypeople.

The trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles

Rosenberg describes in detail this group of muscles that allow the head to be turned and the shoulder blade to be raised. They are innervated by the spinal portion of the XI cranial nerve, meaning the roots originate in the spine at the C2-C4 level of the cervical spine (see more in the section below).

In Treating Autism (p. 177), Rosenberg describes a tension in the sternocleidomastoid muscle in every client diagnosed with ADHD or autism. Based on Long-term developmental outcomes in patients with deformational plagiocephaly (Miller, 2000), Rosenberg pretends that both groups have a flat back of the head (plagiocephaly). This is pure invention–a fallacy of attribution. Miller doesn’t mention ADHD or autism in his article! Trying to associate a flat head with a dysfunction of social engagement and autism is quite a leap.

The “Basic Exercise”

“The goal of this exercise is to enhance social engagement,” promises the author. Holding the head still, readers are asked to turn the eyes horizontally far to the right and then to the left. “After thirty or even sixty seconds, you will swallow, yawn, or sigh. This is a sign of relaxation of your autonomic nervous system.” According to Rosenberg, a direct neurological connection exists between the sub-occipital muscles (neck) and the muscles that move our eyeballs–which don’t belong to the VVC.

Our comment: Muscle stretching induces relaxation — nothing new! A simple exercise proves it quickly.

Instead of stretching the ocular (eye) muscles, slowly rotate your head to each side to the maximum angle possible (if you have no medical conditions). Wait for the yawning! You can also lie on your back and pull your knees toward your head with your hands. This is very relaxing. Most yogic asanas involve stretching (and breathing) to induce peace of mind. This is not a secret, and this is not polyvagal.

Suggesting that the reader may yawn creates an expectation (placebo effect). The sixth cranial nerve (abducens) turns the eye outward horizontally. It's not a branchiomotor nerve (social engagement). CN VI has no direct connection to the ambiguuus nucleus (NA). Also, the deep neck muscles don't belong to the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid groups. The vestibular system (balance), the visual system, the motor control of the eyes, and the neck are constantly adjusting. However, this is done in the midbrain and higher centers.

Sighing is caused by the activation of respiratory centers and the phrenic nerve. Yawning is a complex reflex in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and brainstem. It is executed by muscles controlled by cranial nerves V, IX, and XII. Both branches of the X originating in the NA and DMVN control swallowing. Rosenberg's arguments are, therefore, unconvincing. However, we don't question his manual expertise or the usefulness of his exercises. Only ... they are not even polyvagal.

In his book, Rosenberg presents a collection of polyvagal hypotheses that don't make much sense from a current scientific perspective. Here are a few examples:

The dorsal vagus, acting on its own, brings about a state of metabolic shutdown (2017, p. 41). Fact: The dorsal branch of the sympathetic activates digestion, regulates inflammation, and protects the heart.

Immobilization with fear (p. 41). Fact: The vlPAG (midbrain) activates the immobilization pattern related to the striated muscles. Fear involves higher centers (e.g., amygdala).

Slowdown and energy conservation (p. 42). Fact: Every animal tries to conserve energy. Lions, sloths, bears-all mammals-run only when necessary. Because mammals and birds are endotherms (they produce their own heat), their metabolism is much higher. They need to eat more and more often. It's that simple!

They may contemplate, attempt, or commit suicide. These can all be symptoms of activity in the dorsal branch of the vagus nerve (p. 44). Fact: This is psychiatric nonsense. The dorsal branch plays no role in depression, which involves serotonin- and norepinephrine-driven circuits.

Dissociation (p. 47). Fact: The author confuses dissociation with distraction, depression, and lack of energy. The DSM-5 gives an entirely different definition.

Eric Marlien

Rosenberg has his perfect counterpart in the French-speaking world. In Le système nerveux autonome de la théorie polyvagale au développement psychosomatique (The autonomic nervous system from the polyvagal theory to psychosomatic development), Eric Marlien, a French osteopath, provides a comprehensive presentation of the polyvagal theory (Marlien, 2018). This book presents various osteopathic manipulations from a polyvagal perspective. He uses a symptom questionnaire inspired by Porges' Body Perception Questionnaire. Symptoms such as oily skin, depression, dissociation, nausea, diarrhea, farts, and fainting, to name a few, are all attributed to the "old vagal". Even more surprising are the "new vagal" symptoms: dizziness, hyperglycemia, tinnitus, and more. All of this is far from current medical knowledge. Again, we do not doubt that Marlien is an exceptional body therapist. However, the theory behind his work has too many flaws.

4.1.4

The Accessory Nerve CN XI

As Rosenberg explains, the Accessory Nerve, the 11th cranial nerve, has two components. The upper part originates in the medulla, in the nucleus ambiguus. This motor nerve innervates muscles of the throat, and not of the neck. Most part of the accessory nerve originates from the spine, though. It reenters the skull and exits with the other part, before it separately innervates the superficial muscles of the neck: Trapezoid and Sternocleidomastoidien. Other muscles – such as the Supraspinatus and the Levator scapulae – are deeper muscles, which also participate in the mobility of the head and the neck.

Does the Spinal Accessory Nerve (SAN) belong to the Social Engagement System? Does it belong to the head or to the trunk?

The nerve fibers of the spinal accessory arise from the spinal cord segments of C1 to C5, with the primary contribution typically coming from C1 to C3 or C4. These fibers ascend into the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum, join with the cranial accessory, and, together with the CN IX and X, exit the skull through the jugular foramen to innervate the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

In Is the cranial accessory nerve really a portion of the accessory nerve? Anatomy of the cranial nerves in the jugular foramen, Ryan (2007) questions the existence of one accessory nerve.

Anatomically, the accessory nerve consists of two components: the cranial accessory nerve, which innervates the pharynx and larynx muscles, and the SAN, which innervates the neck muscles, including the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. In Transitional Nerve: A New and Original Classification of a Peripheral Nerve Supported by the Nature of the Accessory Nerve (CN XI), Benninger and McNeil (2010) reviewed papers on anatomical, embryological, and molecular studies. They propose that the SAN is a transitional nerve that belongs neither to GSE (somatomotor CN III, IV, VI, and XII) nor SVE (branchiomotor CN V, VII, IX, X, and XI).

In Evolutionary and developmental understanding of the spinal accessory nerve, Tada et al. (2015) conclude that the SAN is a novel structure specific to living gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates). It arose by repatterning pre-existing spinal motoneurons in the hypothetical jawless ancestor. The ancestral SAN may have acquired intermediate branchiomotor properties through de novo upregulation of cranial nerve-specific regulatory genes (Benninger, 2010). Thus, it is impossible to characterize the accessory nerve based on a simple head/trunk dualism; rather, it is a third category of the peripheral nerve.

Deep muscles of the neck

All four figures from (Sobotta, I, 1922), modified

As we can see, the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius are part of all the muscles involved in moving the head (e.g., rotating, tilting, inclining, or raising the head). Reducing the neck muscles to the first two muscles is a group misconception. It ignores the other muscles and functions of the neck (e.g., those involved in catching food, maintaining balance, and supporting the visual system).

-

The supraspinatus muscle is primarily innervated by the suprascapular nerve, which originates from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, deriving fibers from the C5 and C6 nerve roots.

The levator scapulae muscle is innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve (C5), which also originates from the brachial plexus, and by direct branches from the cervical nerves (C3 and C4).

The suboccipital muscles, which enable the head to rotate and tilt, playing a crucial role in head and neck mobility. are innervated by the suboccipital nerve. This nerve is the dorsal ramus of the first cervical nerve (C1).

4.1.5

Can Stretching Heal the Vagus Nerve?

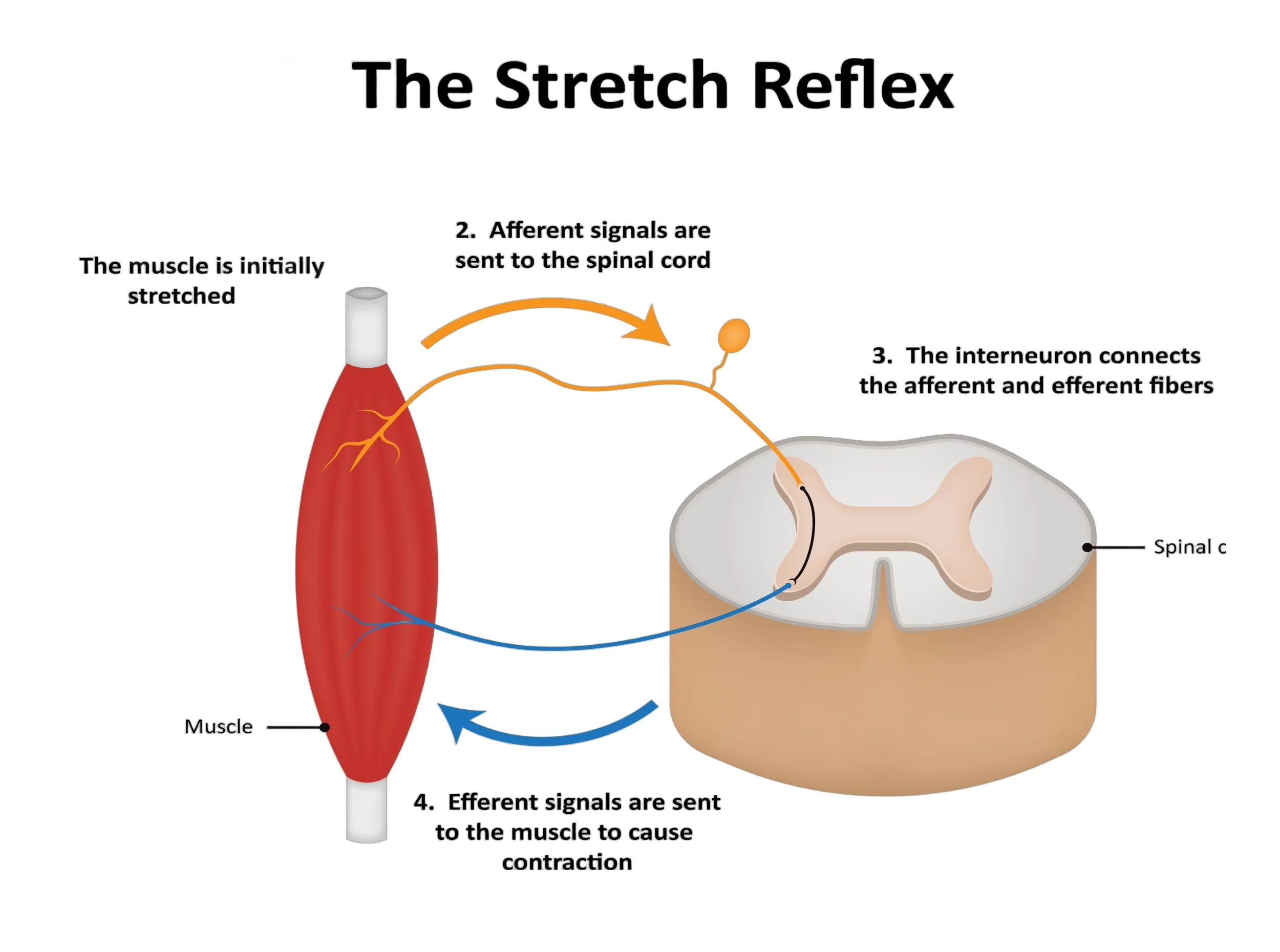

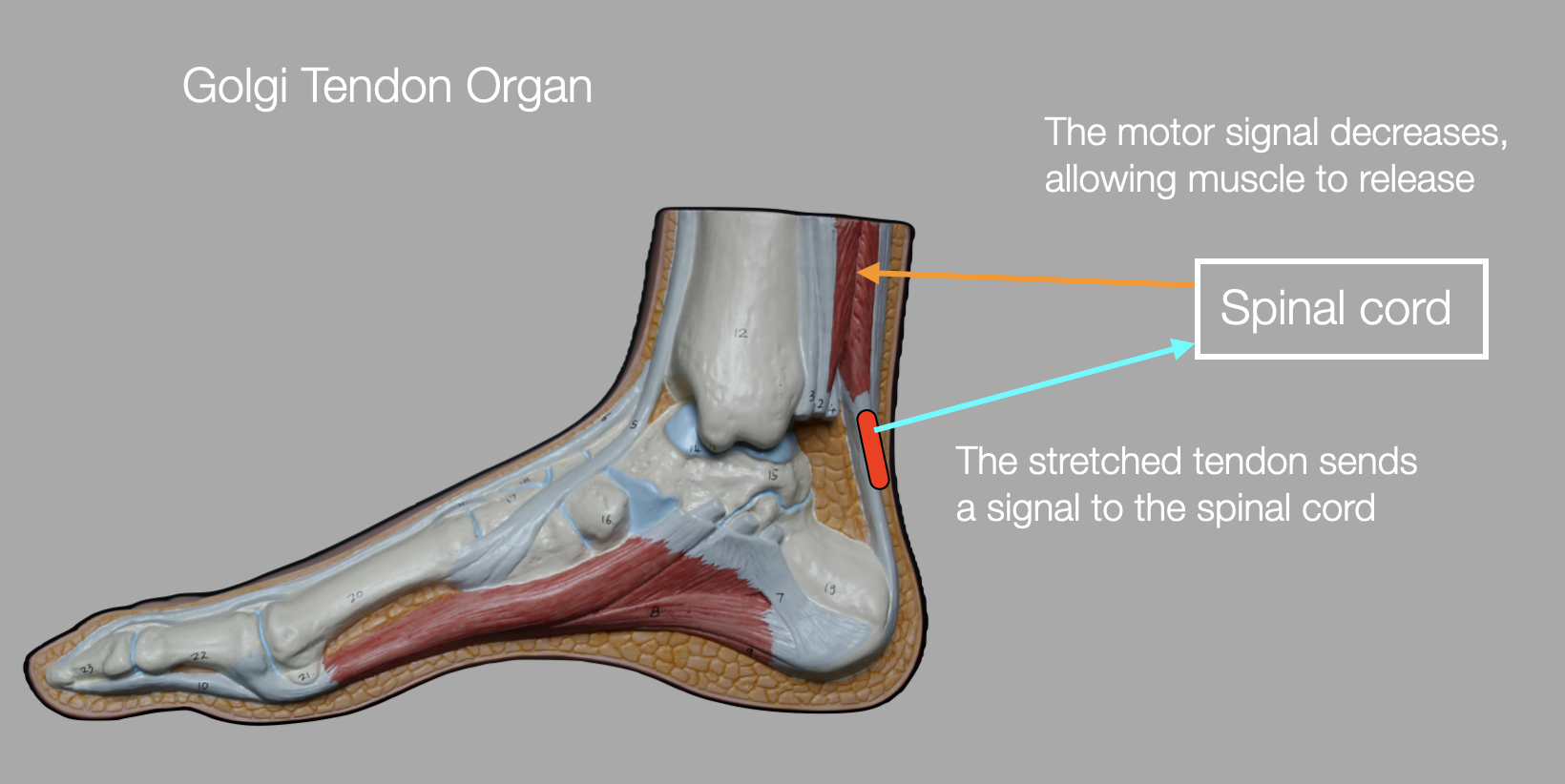

Writers and therapists regularly suggest stretching exercises to heal or trigger the vagus nerve. Again, this is a confusion between the somatic and visceral systems. Muscle stretching stimulates the somatosensory system, which responds with pleasant relaxation. This somatosensory reflex is based on two types of receptors that help the body adapt to effort and movement. Here, we describe two basic reflexes:

Stretch reflex: In the muscles, small muscle fibers with sensors, called muscle spindles, respond to stretching. These send signals to the spinal cord. Through interneurons and efferent motor fibers, a signal is sent to the muscle to cause contraction.

Release: When you stretch a muscle, you may initially feel an uncomfortable pull. After a few seconds, however, the muscle adapts. This adaptation is facilitated by the Golgi tendon organ, which sends a signal to the spinal cord. In response, the spinal cord inhibits the motor signal to the muscle, resulting in less muscle contraction and a feeling of relief.

Yoga asanas (Swanson, 2019), stretching sessions, or Pilates classes all work to release chronic muscle contractions. But they also strengthen the muscles. As a result, the body can better adapt to its needs, alternating between contraction and relaxation. Depending on the situation, we feel safer with a strong and responsive body or, on the contrary, let it go and indulge in laziness. This feeling of strength and security is directly related to our somatic system (somatomotor and somatosensory). However, our muscle tone (e.g., hypertonia or hypotonia) reflects on the cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary systems. Heart and respiratory rates covary with specific somatic states (e.g., exercise vs. rest). In addition, muscles have little dependence on the viscera (e.g., heart, lungs, and digestive system) for the calories and oxygen required for locomotion. None of this should lead us to conflate somatic and visceral, as PVT does.

>> to the next chapter Auditory Training