1.1.0

Origins of the Polyvagal Theory

Aristotle

Scala Naturae

Darwin

Spencer

Jackson

Freud

MacLean

Polyvagal Theory didn't come out of nowhere.

The legacy of ancient and Christian scholasticism paved the way for PVT. No sooner had Darwin rocked the boat than the proponents of the elitist model got back on track, using new biological concepts from the 1950s. That’s why many academics love Porges’ ideas.

1.1.1

Aristotle

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) studied at Plato’s Academy in Athens for 17 years. He expanded philosophy to include nature and spent much time observing and describing life on the island of Lesbos, becoming the first zoologist in history. In his History of Animals (Greek: Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν) he proposed the first classification of living things.

Aristotle was very influential for about 2,000 years. He proposed a hierarchy of living things, from the most primitive (e.g. worms) to humans. This concept of matter and life was shaped in medieval Christianity by the Scala Naturae (scala means ladder or staircase) which described the ascending hierarchy from minerals to plants to animals to humans to angels to God.

The ranking of animals over plants was based on their ability to move and reproduce, with live births “higher” than cold egg-laying and warm-blooded mammals and birds “higher” than “bloodless” invertebrates. This view held until the 18th century when God created each form so perfectly that modification or extinction was impossible. Theologians had calculated the creation date (about 4,000 years before Christ). But in the last two centuries as more and more fossils appeared the existence of animals thousands or millions of years ago became an unavoidable question.

While a great writer and thinker Aristotle believed our planet was at the center of the universe (geocentrism). The Catholic Church held this view for nearly 2,000 years, keeping man in God’s image. But Copernicus (heliocentrism), Darwin and Freud would eventually challenge these concepts.

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right). In “The School of Athens”, Raphael, Vatican.

1.1.2

Scala Naturae

The Scala was made famous by various drawings, the first of which, by Ramon Lull in 1305, described the medieval Scala Naturae as a staircase, implying the idea of progress (ladder of ascent and descent of the spirit). Source Wikipedia.

The Scala Naturae, also known as the Great Chain of Being, is a hierarchical classification of all existence and matter, imagined as a ladder or chain. It was born with Plato and Aristotle in ancient Greece and was developed by scholars and theologians in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The chain starts with God at the top, then angels, humans, animals, plants, and minerals at the bottom. Each level is further subdivided. The Scala Naturae was a big influence on early scientific thought and taxonomy. But its rigid hierarchy was challenged and eventually replaced, first by evolutionary theory and then by modern branching taxonomy (cladistics).

The ladder model

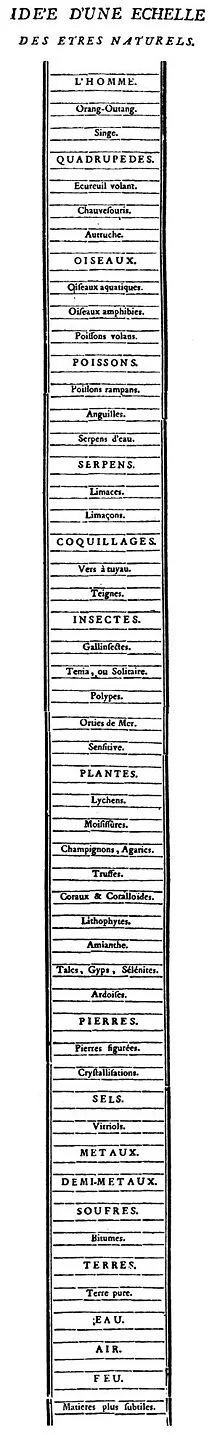

Another version of the Scala Naturae was published in 1779 by the Swiss naturalist Charles Bonnet, which is more of a ladder than a scale. Source Wikipedia. It very much anticipates the ladder proposed by Deb Dana (2018), which illustrates the hierarchical concept of Polyvagal Theory.

Adapted from Dana (2018, p.20).

The ladder model is the core concept of PVT. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how Darwin's successors — Spencer, Jackson, Freud, and MacLean — tried at all costs to preserve the idea of biological and psychological hierarchy. In the next chapter (What?), under “The Ladder Model,” we will see how Porges, relying on Jackson and MacLean, went to great lengths to prove this hierarchical perspective.

1.1.3

Darwin

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth.

— Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) began to repeat Aristotle's work, this time along the coasts of South America and on the Galápagos Islands. The results of his observations were published in “Origin of Species” (1859) and “The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex” (1871). When he introduced the idea of evolution and species selection, there was immediate resistance from his colleagues. But the concept of continuity between our non-human ancestors and ourselves (gradualism) made the scandal reach the masses — and the crown. With his theories, Darwin dethroned man from his exceptional position in creation. The first was Copernicus, who showed that the earth was not the center of the universe. The third would be Freud — man is not the master of his psyche.

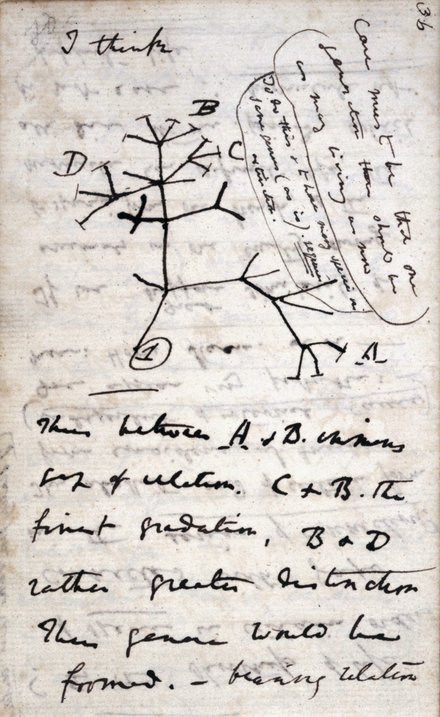

Page from Darwin's notebooks (c. July 1837) with his first sketch of an evolutionary tree and the words “I think” at the top. Source: Wikipedia.

Darwin not only had in mind the deconstruction of the fences between species, but — as a small sketch shows — he doubted the monolithic line of evolution. Evolution is not a single ladder — from plants to God — but more like a coral. This approach foreshadowed the “cladistic revolution” a hundred years later, which placed all contemporary species (whether snails, snakes, or humans) on the same line. From this perspective, it becomes clear that “reptiles” and mammals — both amniotes — may have had a common ancestor, but their evolutionary paths split about 320 million years ago. We, humans, have never been reptiles.

See: The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (Wikipedia).

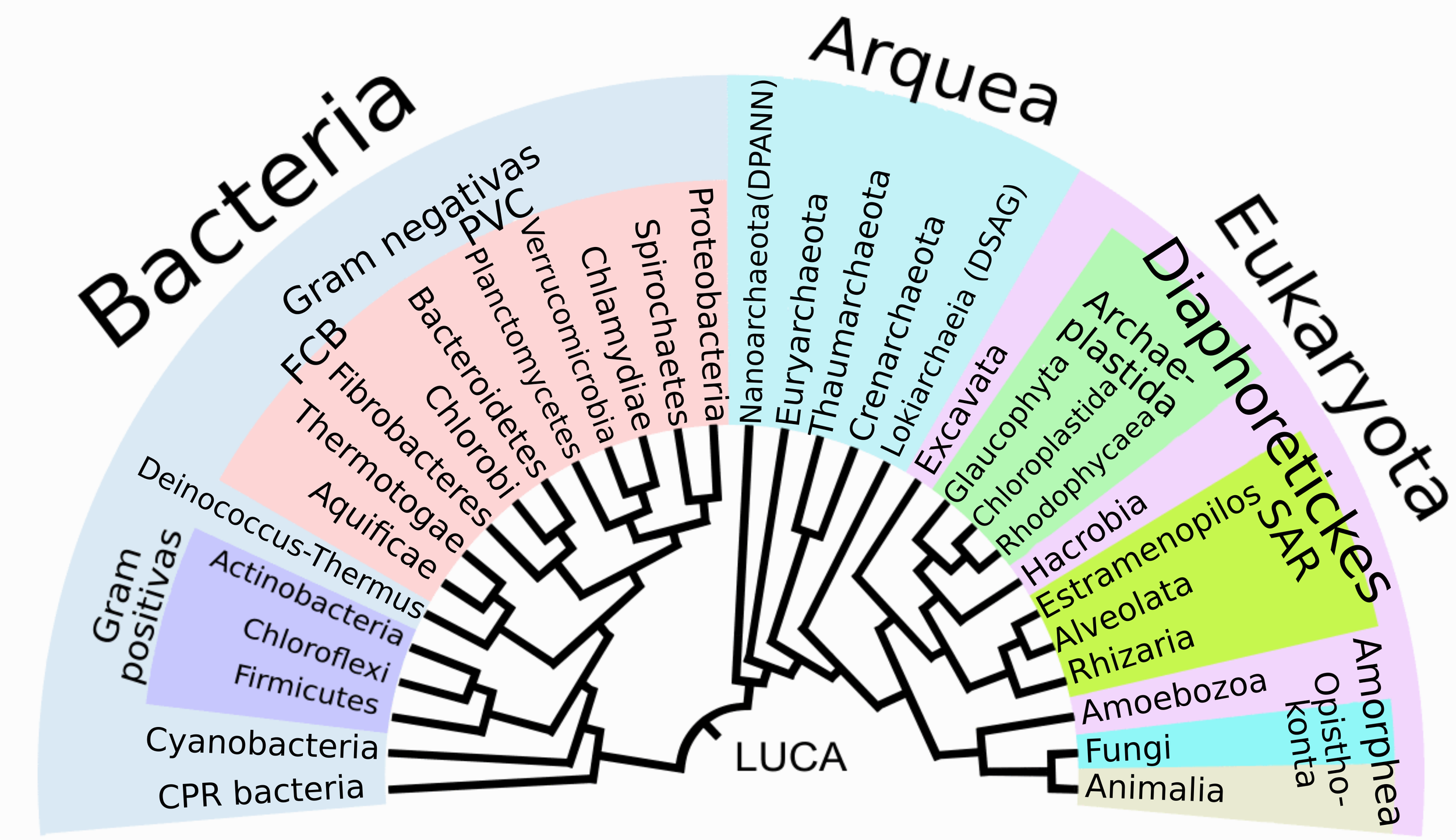

A modern “Tree of Life”: By User: Crionde la traducción Pitana - Commons Phylogenetic Tree of Life.png, CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia.

Diagram in Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859). It was the book's only illustration. Wikipedia

Darwin's account, confirmed by modern science, explains why we cannot use the phrase “our ancestors were reptiles” as Porges does. As we will see later, the two groups, “reptiles” and mammals, originated about 326 million years ago by a radical split (sauropsids vs. synapsids).

Darwin constantly questioned a teleological (purposeful) view of evolution. In a letter to Moritz Wagner dated March 2, 1873, Darwin stated:

“After long reflection I cannot avoid the conviction that is no innate tendency to progressive development, as is now held by so many able naturalists, and perhaps by yourself.”

Although Porges never makes a teleological statement, his entire work is based on the superiority of mammals over “reptiles. The PVT is imbued with progressing from asocial reptiles to communicative mammals.

1.1.4

Darwin's descendants

While Darwin's ideas seemed to be widely accepted by most scientists for the next 150 years, an invisible ideological countercurrent slowly took shape. Different authors in different fields (sociology, psychology, and politics) diverted the idea of evolution by reinforcing the notion of hierarchy in various fields:

sociological — “the fittest wins” — (Herbert Spencer)

neurological dissolution (Jackson)

between races (Galton)

between the conscious and the unconscious (Freud)

between reptiles and primates (MacLean) or mammals (Porges).

Herbert Spencer, who invented the “survival of the fittest” formula, applied the staircase to sociology. Some pushed it further into racist theories, asserting the superiority of the “civilized man” over the “primitive savage."

Francis Galton, a cousin of Darwin, went a step further. He developed eugenics, a theory of “racial improvement” and “planned breeding” that gained popularity in the early 20th century—more on this in The gene : an intimate history (Mukherjee, 2016).

1.1.5

Hughlings Jackson

John Hughlings Jackson (1835-1911), a British neurologist, coined the term dissolution to describe how subcortical parts take control in a more primitive way after the cortical regions of the brain fail. According to Hughling Jackson, there are three levels of nervous system development, each containing a complete representation of the next lower level (York, 1995). Porges, a great admirer of Jackson, describes in The Science of Safety (2022) how, through the dissolution process (Jackson, 1884), higher nervous arrangements are suddenly rendered functionless and the lower increase in activity — as “evolution in reverse.”

In rhetoric, “stretching a metaphor” too far out of context can lead to implausible results. Isn't what Porges, a psychologist by profession, is doing when he tries to appropriate the observations of Jackson, a neurologist, and apply them to psychology? — a category shift. Jackson was talking about epilepsy, tumors, and organic degeneration. Just throwing a tantrum or bursting into tears doesn't create a dissolution process initiated by organic change! But Porges sees an identical process in Jackson's observations and the transition from one behavior (e.g., social engagement) to a more “primitive” behavior — such as fight, flight, or lower, such as immobilization. Polyvagal theory postulates a similar resolution process in the threat context, suggesting three distinct physiological strategies. Just as Jackson described a gradient from the neocortex to the brainstem, Porges — with the same idea of dissolution in mind — reduced this hierarchical organization to a much smaller scale: the autonomic system (VVC, SNC, and DVC).

Hughlings Jackson posited the dissolution of evolved higher functions as the key to clinical conditions in which damage to the nervous system affects a person's ability to function; quoting Spencer, he remarked: “I do not mean, of course, that material actions thus become mental actions ... I am merely showing a certain parallelism between ... physical evolution and correlative psychic evolution. " He didn't interpret neurological disorders and “insanities” as a global regression, as Freud did, or as a behavioral dissolution, as Porges did, but as a “local dissolution of the highest centers” (all quoted in "John Hughlings Jackson: bridging theory and clinical observation” by Gillett & Franz (Gillett, 2013).

What's left of Jackson's theories?

Hughlings Jackson was a pioneer of 19th-century neurology. However, as we know, many neurological disorders can impact subcortical or brainstem areas without cortical involvement, disproving Jackson's dissolution theory. These include:

Parkinson's disease: primarily a disorder of the substantia nigra (midbrain) with dopamine deficiency.

Huntington's disease: primarily a disease of the basal ganglia (striatum).

Various brainstem lesions may occur without cortical involvement and result in unique clinical syndromes such as locked-in syndrome.

Guillain-Barré syndrome: a peripheral nerve disorder that does not involve the cortex but causes profound neurological deficits.

Therefore, we cannot apply Jackson's principles to psychology if this neurological model is limited to a few neurological disorders– incorrect for the rest.

1.1.6

Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), a neurologist and great admirer of Darwin (and Jackson), also postulated a hierarchical structuring of the mind, from the lower unconscious regions of the psyche to the higher conscious ones. The unconscious is the place of lower instincts (e.g., sexual desires or the father's murderous fantasies). Our goal should be to sublimate our impulses and bring consciousness where there is unconsciousness.

I recommend reading Stephen Gould's chapter on Freud in Ontogeny and Phylogeny, which deals with the recapitulation theory and how Freud tried to link psychology and history — or a fictional version. I also appreciated the book Freud, Biologist of the Mind (Sulloway, 1992), which describes how Freud vehemently tried to adapt Darwin's theories to psychoanalysis.

Sigmund Freud often combined psychological analysis with imaginative narrative, as in his interpretation of the father's murder by the primal horde, a speculative story rooted in myth rather than history. His analysis of Leonardo da Vinci, in which he wove together art, biography, and psychoanalysis, also shows his tendency to fictionalize to explore deeper truths. Freud's approach, influenced by thinkers like James Frazer, whose imaginative reconstructions of ancient customs (The Golden Bough) also blurred the lines between history and myth, is a testament to the impressive depth of his intellectual exploration.

In Facticity, Freud, and Territorial Markings (cited in Borch-Jacobsen, 2005), Cioffi and Esterson answer the question: Was Freud a liar? They say: “Freud had an uncanny ability to say anything and everything.” The authors describe how the strange neurosis theory has helped modern society relax about sexuality, which is great. They also ask why the best and most intelligent people in our culture refused to use normal intellectual methods of inquiry when it came to Freud. Similar questions will appear when I later ask why some famous psychologists and psychiatrists did not hesitate to adopt the PVT.

1.1.7

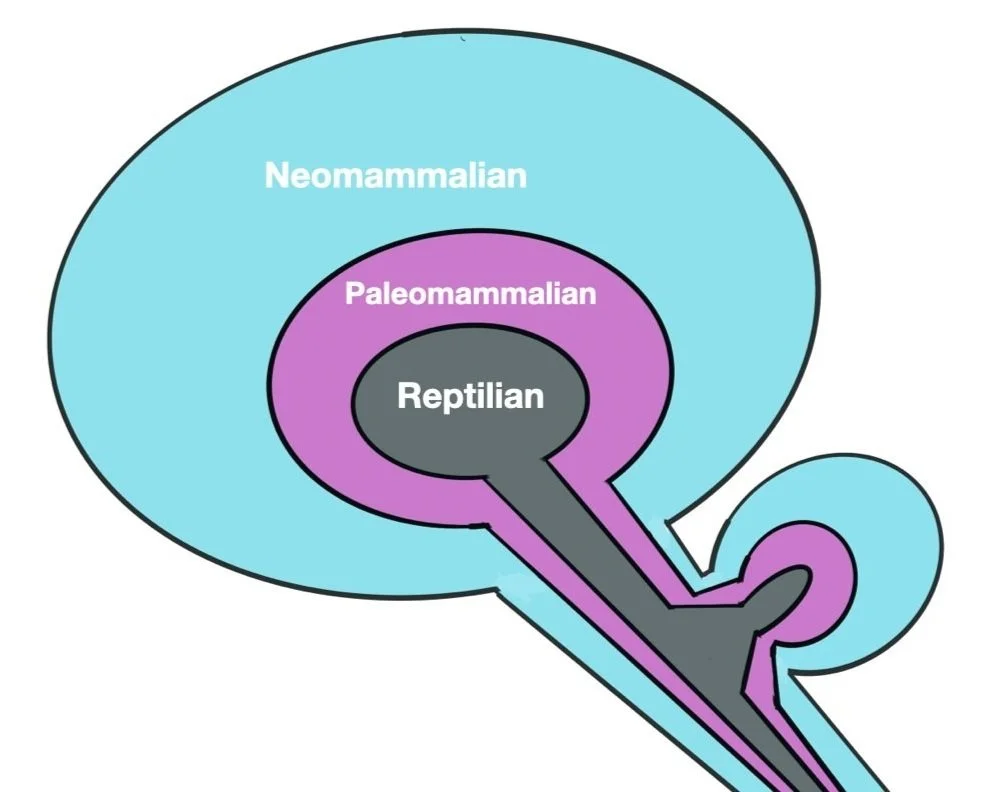

Paul D. MacLean and The Triune Brain

A medical researcher and psychiatrist from Chicago, Paul MacLean, conducted several experiments on monkeys around 1950, mutilating about a hundred to show that lower brain structures were responsible for rigid and aggressive behavior. No one has or could replicate these experiments.

“For much of the past 50 years, MacLean has been telling us that our brains are an assemblage of neural systems that have very different evolutionary histories and underlie very different behavioral endpoints. To master our best potential, and subordinate our worst attributes, we must comprehend and bring under rational control our entire neural machinery.” (Newman, 2003)

MacLean suggested that our three brains don't necessarily communicate or work well together because of their different "mentalities." Echoing Freud, he saw this conflict as the primary cause of our mental problems. See also (MacLean, 1949, 1952, 1973, and 1990) and Wikipedia: Paul MacLean and Triune Brain.

The Triune Brain, adapted from (MacLean, 1967)

1.1.8

Carl Sagan and the Dragons of Eden

In the 1970s and '80s, aspects of Dr. MacLean's model were popularized by astronomer Carl Sagan in The Dragons of Eden (Sagan, 1977) and novelist Arthur Koestler in The Ghost in the Machine (Koestler, 1967). In Science in the Soul (Dawkins, 2017, p.213), the famous atheist biologist Dawkins describes various scientists prone to fantasy. Of all of them, “Carl Sagan was a virtuoso.”

Carl Sagan naively writes:

“Deep inside the skull of every one of us, there is something like a crocodile's brain. Surrounding the R-complex is the limbic system or mammalian brain, which evolved millions of years ago in mammal ancestors but not yet primates. It is a major source of our moods, emotions, concern, and care for the young. And finally, on the outside, living in an uneasy truce with the more primitive brains beneath is the cerebral cortex; civilization is a product of the cerebral cortex.”

— Carl Sagan, Cosmos p. 276–277

To what, Naumann replies in The reptilian brain (2015):

Carl Sagan’s amusing words of wisdom notwithstanding — is the H-bomb not also a product of the cerebral cortex? — is the reptilian brain just a mammalian brain missing most of the parts? Some 320 million years ago, the evolution of a protective membrane surrounding the embryo, the amnion, enabled vertebrates to develop outside of water and thus invade new terrestrial niches. These amniotes were the ancestors of today’s mammals and sauropsids (reptiles and birds).

In The Hope Circuit (2018, p.99), Martin Seligman (one of the developers of Learned Helplessness and Positive Psychology) mentions his friendship with Carl Sagan. When he read the script for Dragons of Eden, “a book about the brain,” Seligman advised Sagan not to publish it because “the psychology in it was too sloppy.” Seligman gave him The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Kuhn, 1962) to read, but it didn't help. Sagan did it anyway and won the Pulitzer Prize!

MacLean, Sagan, and Koestler revived a literary genre: the science novel. Herodotos (480-425 B.C.), the “father of liars,” who is even credited with creating the “school of liars,” initiated the tradition. Among other things, he invented the “tears of the hypocritical crocodile.” He would have loved the Internet! But what is immensely worrying here is how narrative qualities — once again — take over reality. As the aphorism of Giordano Bruno (1582) says: “Si non è vero, è ben trovato” (If it is not true, it is a good find).

1.1.9

MacLean’s Legacy

Many proponents of Polyvagal Theory, including Pat Ogden, Allan Shore, David J. Spiegel, Peter Levine, and van der Kolk, frequently refer to MacLean. These proponents rarely avoid mentioning the Triune Brain, often devoting entire pages to the topic.

In The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic Contributions to Social Behavior, Porges (2003) celebrates MacLean's contributions to understanding the vagus nerve's role: ”The Polyvagal Theory is a new conceptualization of the role of the vagus nerve. It employs several features MacLean emphasized, including the importance of evolution, limbic structures, and vagal afferents. The Polyvagal Theory builds on these early findings by MacLean and focuses on the link between phylogenetic changes in the autonomic nervous system and social behavior.”

In Waking the Tiger (1997), Peter Levine often refers to the Triune Brain concept to explain the Somatic Experiencing approach to trauma healing.

Similarly, in The Body Keeps the Score (2014), van der Kolk devotes entire pages to discussing MacLean and the reptilian brain.

Cozolino also wrote a complementary article about MacLean.

Panksepp, who polyvagal proponents often quote, wrote extensively about the triune brain.

In addition, Ploog (2003) explored the place of the triune brain in psychiatry. In Plato's Neurobiology, a philosopher, Elizabeth Laidlaw (2012), explains how Plato's work — an adept of a triune brain before the date — connects to MacLean's concept of the triune brain. Again, we see the danger of mixing different categories-philosophy and biology.

In short, to assess an article's affiliation with Polyvagal Theory, first consult the bibliography — and the index if it's a book. Look not only for keywords like “polyvagal” and “Porges” but also for “MacLean” and “triune brain.” “Limbic system” is also a red flag. If you find these terms, there's a good chance the text was written with a hierarchical view of the brain—more on hierarchy.

1.1.10

MacLean Debunked

The scientific community has criticized no scientific writer more than MacLean. You can start with the “Triune Brain” article on Wikipedia to get a first impression.

Three groups of top experts in neuroanatomy and neurophysiology represent the following sources:

Butler and Hodos condemn MacLean's ideas in “Comparative vertebrate neuroanatomy: evolution and adaptation” (Butler, 2005, p.114).

Bear et al. (2016, p. 621-625) explicitly criticizes MacLean and, more generally, the idea of a single system for emotions in Neuroscience : exploring the brain.

Joseph Ledoux describes in The emotional brain: the mysterious underpinnings of emotional life (1996, chapter 4) how the James-Lange vs. Cannon-Bard debate developed. He then devotes ten pages to the MacLean hypothesis of the limbic system and concludes, “I must say that it (the limbic system) doesn't exist” and “it must be abandoned.” See his recent article: The Deep Story of Ourselves (Ledoux, 2023).

Further Reading

DeSalle and Tattersall, in The Brain: Big Bangs, Behaviors, and Beliefs (2012), provide candid commentary: “Limbic” and “triune” are also dirty words. They also quote Reiner's fiery article: You cannot have a vertebrate brain without basal ganglia (2009).

Vocal Communication and the Triune Brain (Newman, 2003).

The triune brain in antiquity: Plato, Aristotle, Erasistratus (Smith, 2010).

Recently, Steffen wrote a critical article: The Brain Is Adaptive Not Triune (2022)

Even Wikipedia has dedicated a short page to the Triune brain myth: « MacLean imposed a phylogenetic gloss on brain anatomy, arguing that the brain was structured in a hierarchical fashion because it had evolved that way. The so-called triune brain is a myth. Experts in brain evolution no longer take it seriously. Nevertheless, it arises again and again in the history of science”.

In How emotions are made : the secret life of the brain (2017, chap. 4), Barrett writes: “This illusory arrangement of [brain] layers, which is sometimes called the “triune brain,” remains one of the most successful misconceptions in human biology.”

Anton Reiner has researched the basal ganglia (Reiner, 1998, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011). In You Cannot Have a Vertebrate Brain Without a Basal Ganglia (2009)- which, by the way, doesn’t mention MacLean — Reiner writes:

The notion of the serial appearance of the parts of the basal ganglia is reflected in the frequent use of paleostriatum and neostriatum as synonyms for globus pallidus and caudate–putamen, respectively. Moreover, in older theories of basal ganglia evolution, the cerebral cortex was thought to supplant the basal ganglia in motor control in the mammalian lineage, replacing a supposed reptilian stereotyped motor repertoire with the adaptable mammalian motor capacity. Modern evidence shows that both striatum and pallidum have been the basal ganglia constituents since the earliest jawed fish (Out of the abstract of the Author Copy- ResearchGate).

Grillner and Robertson in The Basal Ganglia Over 500 Million Years (2016) back Reiner.

Finally, for readers who know French, there is an extraordinary book by Sébastien Lemerle (2020), Le Cerveau Reptilien, which develops an in depth critique of MacLean's work over 220 pages. Lemerle shows the relations between MacLean and Freud and how the popular press picked up the “reptilian brain” meme.

>> to the next chapter: Porges and his Family