5.1.0

Alternatives to the Polyvagal Theory

The PVT provides a neurophysiological framework that leads to a number of practical applications. In the previous chapters, we spent a lot of time challenging the Polyvagal Theory. Before presenting our model, let's see if other existing models can compete with the PVT.

5.1.1

Past Therapeutic Models

Freud and his legacy

The first modern model to be considered is psychoanalysis. Around 1900, Freud, a neurologist, created a model of codified intervention to help patients understand their problems (e.g., depression, “hysterical manifestations,” or impotence). This one-on-one model was not new, as most religious traditions already knew this personal work. Christian, Buddhist, Sufi, Jewish, Taoist, or shamanistic practices have long followed a similar leader-student framework. However, this encounter had a religious character, often involving exercises or reading sacred texts. In the last three decades, psychoanalysis has lost its influence in the therapeutic scene and is not appropriate for body-centered therapists anyway. It is also hardly applicable to psychotraumatology.

Freud offered a non-religious approach, but his therapeutic sessions were a ritualized event. The unique and peculiar characteristics of the psychoanalytic cure, which provided a sense of uniqueness, certainly contributed to the success of the Freudian cure. In addition, Freud proposed a new theory of the human soul with a scientific flavor. Part of the cure was to make the patient adhere to his belief system, such as conscious vs. unconscious, the Oedipus complex, transference, or repression of drives. As in the case of PVT, the stranger the story, the more patients find it interesting and superior to conventional narratives. Like MacLean or Porges, Freud tried to extend his view to as many fields as possible (e.g., ethnography, sociology, art). His followers applied his theories to autism (Bettelheim), education, homosexuality, and even business management.

Psychoanalysis is essentially a top-down model. Its goal is to expand the territory of the conscious over the unconscious through language. In this system, the sexual libido is the dominant driving force. His follower, C.G. Jung, also used the concept of libido, but in a much less specifically sexual way. With the decline of psychoanalysis, a popular theory like the PVT was able to fill the void.

Further Reading

Freud, biologist of the mind : beyond the psychoanalytic legend (Sulloway, 1992)

In A chacun son cerveau (Ansermet, Magistretti, 2004), a psychoanalyst and a neurobiologist try to describe the connection between psychoanalysis and neurobiology, but they barely succeed.

5.1.2

From the Mind to the Body – Wilhelm Reich & the Bioenergy

Virtually forgotten by history, but a key figure in the evolution of psychotherapeutic practice, Wilhelm Reich, also a student of Freud, transformed Freud's intellectual approach into a revolutionary practice centered on the body and sexuality. “Don't talk, make love” could have been his slogan long before the hedonistic anti-war movement of the 1960s. Alexander Lowen, an American physician, was also thinking about the connection between the mind (e.g., depression vs. wellness) and the body (e.g., exercise and sexuality). Lowen met Reich in 1940, first as a student and then as a patient. Reich had developed a bottom-up perspective that focused on the autonomous system. The therapeutic goal was to restore the lost balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems (similar to D. Siegel, 2012: hyperactive vs. hypoactive.) Reich's work was practical: through breathing, shaking, or grounding, the patient learned to let the “vital energy” circulate. With Pierakos, another student of Reich, Lowen founded the Institute of Bioenergetic Analysis in New York in 1956, later becoming an international organization. Bioenergy (sometimes called bioenergetics) combines physical exercises with verbalization (see https://bioenergetics-nyc.org/bioenergetics). Reich established the concept of bodywork, which was continued and transformed by Lowen and many adventurous pioneers (e.g., Navarro in Naples, Gerda Boyesen).

Analyzing the Reichian concept of "body armor" and the exercises proposed by Bioenergy, we find a basic therapeutic principle: movement is the main tool to dissolve rigidity. This is very close to the work of Peter Levine. A student of Lowen would say that Levine is doing Bioenergy. However, the addition of the animal model of freezing and some elements of psychotraumatology gave Somatic Experience© a new dimension.

5.1.3

Current Alternatives to Polyvagal Theory

The Neurovisceral Integration Model (Thayer, 2000), which emphasizes the interaction between the brain and the heart, is the only current alternative to the PVT that integrates the autonomic and central nervous systems. However, his work is difficult for the non-academic reader and doesn't offer the hacks and exercises of the PVT.

The Structural Dissociation Theory (van der Hart, 2007) is an exciting discovery encompassing brilliant theory and solid practice. Unfortunately, it is too subtle and sophisticated for many practitioners who don't treat patients with Dissociative Identity Disorders (DID) anyway. A perfect theory for treating complex psychotrauma, the SDT doesn't apply to everyday life issues.

Of course, many therapeutic techniques (SE, EMDR, EFT, DBT, hypnosis, or NLP) have some theoretical body, but no one since Freud and before Porges has proposed such a versatile theory that addresses so many issues — evolution, autism, psychotraumatology, neuroanatomy, and more. Polyvagal hubris is quite a thing! Because it has spread into so many areas with so little resistance, it may take years to challenge it and set things right specifically.

5.1.4

Structural Dissociation Theory

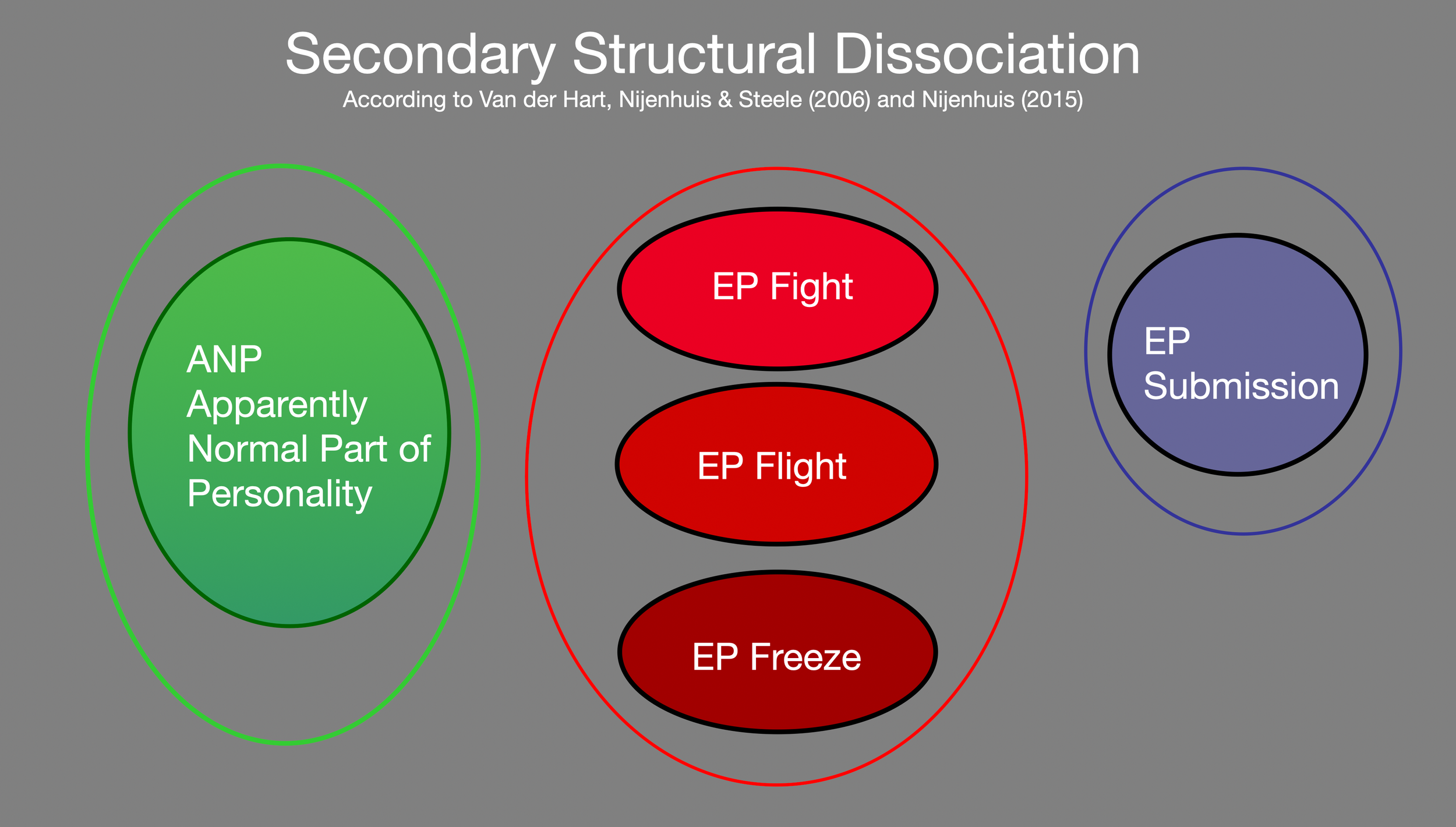

Why has PVT attracted structural dissociation experts? Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele (van der Hart, 2006) built their theory around fault lines, dividing the personality into different parts: the Apparently Normal Part (ANP) and the Emotional Parts (EP). In secondary dissociation, a new division appears between two types of EP: aggressive (mobile) vs. submissive (immobile) emotional parts. At first glance, this model corresponds perfectly to the three levels of the PVT. Readers need to understand, however, that Structural Dissociation Theory (SDT) doesn't suggest a naive dichotomy between social, agreeable, and empathetic parts vs. asocial, savage, and aggressive parts. The socially adapted part (ANP) certainly brings the client to the therapist. However, it often lacks the necessary empathy for the suffering emotional parts. It doesn't want them to exist. It feels constantly threatened from the outside (society and possible predators) and from the inside. (emotional parts). The ANP is also generally powerless and avoidant. We are in shallow water here. That's why the three-layered PVT does not overlap with the SDT. The “ventral” is not identical to the ANP, nor are the “sympathetic” and “dorsal” with aggressive and submissive EPs.

Polyvagal considers only the perspective of the victim

The PVT is built around the perspective of the victim, not the predator. On the contrary, Peter Levine sometimes switches perspectives when treating trauma. How does a lion feel about attacking a weak antelope?

Similarly, the aggressive EP (internalized predator) doesn't suffer. The primary threat comes from the “nice” therapist who tries to protect the ANP and challenge the internal organization. The submissive part is often in a state of fear, which is sympathetic arousal. Remember, the dorsal vagus stimulates digestion, which is blocked during a life-threatening situation. Finally, it's hard to imagine a phylogenetic change every time a person with DID moves from one state to another.

As noted above, the field of structural dissociation is far too complex to allow a theory like the PVT to be applied to clinical psychotraumatology.

Can the Three-State Energy Model provide what the “structuralists” seek? Perhaps. Interestingly, authors such as Reinders, Schlumpf, and Nijenhuis (Reinders, 2006, 2014, 2019, 2021) (Schlumpf, 2014) (Simone, 2012) have observed that the different parts often differ in metabolism. The ANP is low to medium energetic. Aggressive EPs can be full of energy, while submissive EPs tend to be quiet — and, therefore, low-energetic. Still, we shouldn't create fixed portraits — as polyvagal supporters typically do — because parts of the personality can take many forms. Childish parts can also be very persistent, using their suffering and needs as leverage. They can keep the therapist on his toes.

Diagram: In this highly simplified view, based on the work of van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele (2006) and Nijenhuis (2014), we see how different parts relate to different energy levels. Freezing combines immobility (blue) and sympathetic excitation (red). N.B. In reality, the parts are much more intertwined.

In DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder), each Personality Part (PP) has a different character and energy state. The Apparently Normal PP (ANP) has a low to medium energy level because it strives for normality and social adjustment at the expense of emotional integration. The reader must understand the oversimplification here. PPs don't fully follow this energetic dynamic.

Emotional parts (EP) can be aggressive (toward other people and parts of the system). They have a lot of energy and are dominant.

Emotional parts can also be submissive and lacking in energy. Many parts are “children” — submissive and hidden, but sometimes tyrannical and manipulative.

>> to the next chapter Three-State Energy Model